He'll always have Paris: Floyd Landis returns to the Tour de France

Watching the Champs-Élysées stage with 'the perfect fall guy'

Antoine Vayer steps out of an elevator in the Hyatt Regency Hotel in Paris, and strides purposefully towards the conference room that houses the press corps of the Tour de France during its final stage, with Floyd Landis and a group of Landis' friends in tow. The former Festina coach turned provocateur is here to file his final column of the race for Le Monde and rattle some cages in the process.

Landis? Well, he's sort of tagged along to see what happens.

Vayer and Landis are wearing grey t-shirts bearing the legend 'Floyd's of Leadville' and the group draws double takes as the Frenchman guides them through the maze of corridors, but their progress is arrested at the door of the press room. The path is blocked by two security guards, one burly and one wiry.

Undeterred, Vayer flashes them his accreditation but none of his four companions have a lanyard, and the two guards hold an impromptu conflab. The wiry guard is adamant that they shall not pass, but the burly guard argues for a more relaxed door policy, immediately recognising the red-haired man with the beard and the shy smile. "This man won the Tour de France," he says, pointing at Landis. "Let him through."

It's quickly apparent that the wiry guard's greatest fear is that Landis might cause a scene. He shoots a wary look at Landis' friend and business partner Scott Thomson, and, perhaps mistaking his muscular frame for that of a bodyguard, reluctantly relents. They are all allowed in. Vayer bustles into the room and ostentatiously whisks out his laptop, while his four companions tip-toe quietly behind him, speaking in hushed tones as though entering a church.

Landis pulls up a pew at the back and taps self-consciously on his mobile phone, though the room is half empty at this point in the afternoon and only a handful of reporters seem to have clocked his presence. All the while, the security guards are deliberating with members of the Tour's press office, and within a couple of minutes, the wiry guard is hovering over Landis once again. "I'm sorry, but you have to leave," he says politely but not exactly apologetically. "Rules are rules."

Falling foul of the Tour's rules again, ten years on. This is too much even for Landis, who bursts into laughter as he stands up. "This is not 'Nam, this is the press room. There are rules," he says to Thomson. The Coen Brothers have a line for every situation.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

As Landis and his friends bid farewell to Vayer and retrace their steps, trudging back out of the press room, the burly guard shakes his head sadly. "I'm sorry," he tells Landis, and extends a hand in commiseration. "You'll always be a champion."

***

When Landis won the Tour in 2006, French magazine Vélo put him on the cover with the caption 'Le Tour à visage humaine.' The Tour with a human face. By the time the edition hit the newsstands, however, it had already been announced that Landis had tested positive for testosterone and he would later recall trying to hide that same face as he made his way through Charles De Gaulle airport after the news broke.

It has taken a decade for Landis to return to France at all, and he is accompanied on the trip by his partner, child and three close friends. The 40-year-old knows that timing the visit to coincide with the end of the Tour will be viewed by many as simple guerrilla marketing for his new Colorado-based marijuana business, the aforementioned Floyd's of Leadville.

"It wasn't by design," says Landis, now installed with his friends in the bar in the hotel lobby, while the muted television behind him shows Chris Froome and the Tour peloton ambling through the opening kilometres of the final stage. "I've wanted to come here because I wanted at some point to come back. I didn't know how long it was going to take.

"It took a long time until I felt comfortable being around it. I went through a lot of emotions and most of the time I was ashamed, other times I was angry. At this point in time, I've been away from cycling for long enough that most of my feelings about cycling are good. I like watching. I'm sceptical of everything, but that doesn't detract from my appreciation for what they're doing."

Landis was only the second Tour winner in history to be stripped of his title after Maurice Garin in 1904 (Lance Armstrong and Alberto Contador have since experienced the same fate), but nobody's fall from grace was as abrupt or as traumatic as his. Feted as Tour champion on the Sunday evening, Landis was cycling's greatest villain within 72 hours. Shortly after his return to the United States, his friend and then father-in-law David Witt committed suicide. His own life went into freefall. Even at a remove of ten years, Landis cannot divorce his memories of the race itself from its distressing aftermath.

"I've never been able to do that. It was two extreme emotions that just merged together and I can't or I'd rather not express them," Landis says quietly. "I don't think I could even if I tried, but I haven't tried. I'd rather just watch from a distance at this point and not feel anything."

The most enduring – and absurd – feat of Landis' 2006 Tour win came on the road to Morzine on stage 17, when he attacked 128 kilometres from the finish and won by almost six minutes to move back to within striking distance of the yellow jersey. While other, similar exploits from the 1990s and 2000s are celebrated to this day – the Montagna Pantani award at the Giro d'Italia, for instance – there was nary of mention of Landis in the official guides when this year's Tour revisited the Joux Plane and Morzine. To all intents and purposes, he has been expunged from Tour history.

"I think that's what hurt me so bad for so many years: they'd have Eddy Merckx handing out medals on the podium at the Tour de France. That dude tested positive three times," Landis says. "I think I went too fast. There's a limit. You can only go so fast on a bike before they go 'Ah, fuck it, that's it, that wasn't cool: make it look realistic.' Maybe that was the whole point, maybe I fucked that up."

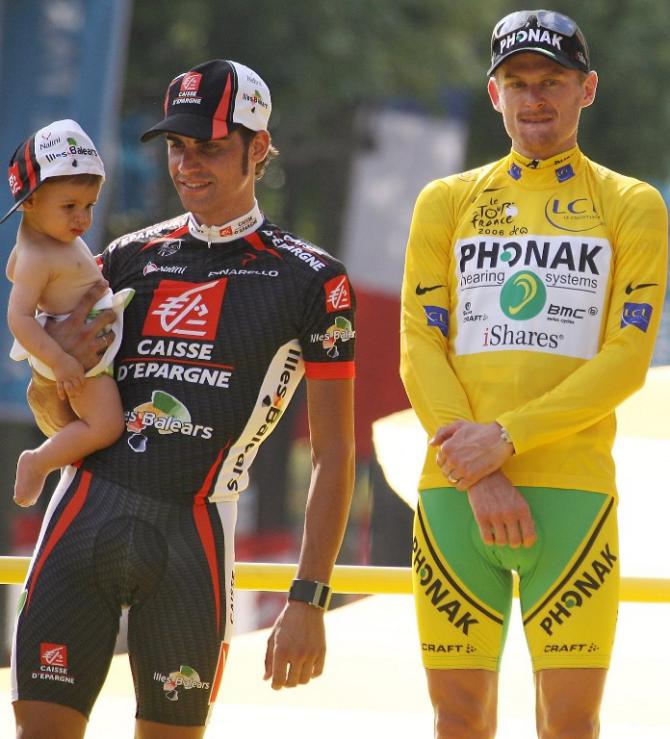

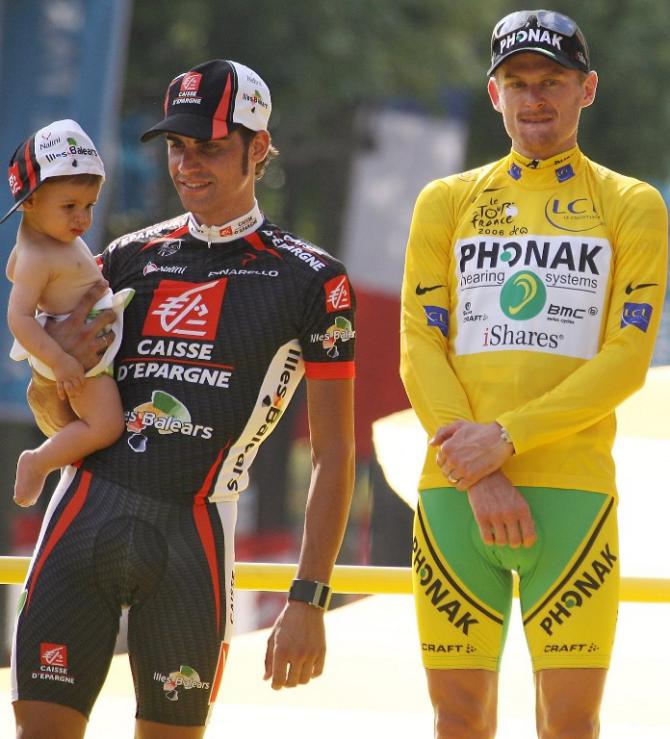

Victory at the 2006 Tour was eventually assigned to Oscar Pereiro, and ASO marked the occasion by playing a video before the belated presentation ceremony that showed Landis' image being broken into shards, like a smashed window. Casting him as the pantomime villain, was, Landis felt, a charade on the part of the Tour organisers.

"That was just beyond hypocritical. [Christian] Prudhomme for doing that, he's a fucking coward. All of ASO knew what was going on, so for him to pretend like Floyd Landis was the guy who invented doping… Fuck him," he says now.

By that point, in late 2007, Landis was out in the cold after unsuccessfully appealing against his ban, cobbling his legal fees together with donations made to the 'Floyd Fairness Fund.' Where Contador, for instance, had the backing of both the Astana and Saxo Bank teams following his positive test for clenbuterol at the 2010 Tour, Landis was immediately cut adrift by Phonak and curtly informed that Andy Rihs' outfit would deny all responsibility for his actions. He is not sure, however, whether the lack of support from his team played any particular role in his being cast so deep into the wilderness.

The rehabilitation of dopers has been a curiously inconsistent phenomenon in professional cycling over the years, a sort of redemption à deux vitesses. David Millar and Ivan Basso were welcomed back to the top level, for instance, but Michael Rasmussen and Davide Rebellin were not. The whys and wherefores are not always immediately apparent. To this day, Landis doesn't believe there is anything he could have done differently in 2006 – a prompt confession like Millar's, perhaps – that would have facilitated a return from suspension at a grander destination than American domestic outfit OUCH.

"I have no idea how that works," Landis says. "But at that point, there was nothing I could do. This tension had built up for seven years, because the press knew Lance was doping. They resented it but they didn't want to write it or were scared to write it. Then I came along and this was the perfect time to write what they've wanted to write forever and they could just crucify me. So from day one, there wasn't a thing I could do.

"There wasn't any way I was ever going race a bike again, no way. I guess in my heart I kind of knew, but I didn't want to accept that it was that easy for the whole thing to just end. But if I look back, that's what happened.

"I mean, Lance just flaunted it. He won the Tour seven times. That's too many, he should have stopped. Then I came along and it was 'Alright, that's enough.' And I didn't have the resources or the PR team or anything. I just wasn't prepared. So I was the perfect fall guy for it, and there was no fucking way they were going to take back anything they said. From day one, that was it."

***

Landis' story can never be fully extricated from Armstrong's, not least because as the whistle blower in the United States Department of Justice's case against the Texan for federal fraud, he stands to collect up to 25% of any damages recouped. Armstrong's legal team have looked to have the case thrown out, but it increasingly seems that he will have to decide whether to reach a settlement with the government (and Landis) or risk incurring greater losses in the courtroom.

Everything that Armstrong has had taken from him in recent years – the seven Tour titles, the endorsement deals with Nike et al, the Livestrong foundation – stems from Landis' 2010 decision to press 'send' on a series of emails detailing the doping practices he had undertaken on the US Postal Service team with the Texan. Even now, Landis can't say if his desire to tear the house down was driven purely by anger and frustration at his own lot – he had been deemed persona non grata by everyone from Armstrong's RadioShack team to the Tour of California – or a genuine wish to change the broken systems governing the sport at large.

"There was nothing left to do except tell the truth and see what happened," Landis says matter-of-factly. "Up until that point, I was covering for people who had been my colleagues for ten years, but once there was no real incentive to keep covering up… Part of it was selfish, I just needed to get it off my chest and tell the truth. But part of it was hopeful that something would change and it would get better. But it didn't, so… fuck it."

Landis' evisceration of the Armstrong myth made him a most unlikely hero to some, but he scarcely noticed any change in public perception in the months that followed. Armstrong hired spin doctor Mark Fabiani, the so-called 'Master of Disaster', to lead a public relations offensive that repeatedly couched Landis as something akin to the Travis Bickle of cycling. Landis found his accusations being dismissed in public by men like Millar, Christian Vande Velde and Bradley Wiggins.

"After 2010, it didn't feel like it got better immediately," Landis says. "There was some support but it was also depicted as a conflict between Lance and me. There was a bunch of people who supported Lance that all of a sudden were new adversaries, or would ridicule me."

By the time Armstrong finally confessed to doping in January 2013, the US Anti-Doping Agency had already claimed to have unmasked what it termed "the most sophisticated, professionalized and successful doping programme in history." The bulk of the heavy lifting, however, was performed by federal investigator Jeff Novitzky, and without Landis, even he would have struggled to amass the evidence that he did.

"I don't want any credit but it bothers me that they're out there saying 'Look what we did.' You didn't do anything, you were just standing there. You were just a bystander and got the credit for it," Landis says. "If USADA was serious, they'd have gone after USA Cycling. They know who was in on it. I told them. [David] Zabriskie told them. Multiple people told the president of USA Cycling, Steve Johnson, but nothing happened. He stayed as president until last year and then retired. So USADA's not about cleaning up sports, USADA's about its own money-raising efforts."

***

On the television behind Landis, the peloton reaches the outskirts of Paris, and somebody suggests they'd better set out for the Champs-Élysées soon, but without conviction. Conversation at the table instead turns to figuring out which sprinters are left in the race as Bryan Coquard's mother is interviewed on the roadside. "Everybody hates this stage, it's so fast on the circuit," Landis explains.

Landis has watched most of this year's race, and his thoughts on Froome's dominance are succinct. "We know the script. We've seen this before. We also know the ending, which is fine. You just enjoy it, and then the movie's over and you start a new one," he says. Like ten years ago, the maillot jaune faces questions over his credibility, even if the line of inquiry has not been as forthright as it was during Froome's first two Tour wins.

"Even if you ask a guy directly if he's doping, you know what he's going to say, so what's the purpose of that?" Landis notes, though he pokes gentle fun at the idea that one of the most persistent investigators of his old US Postal team, David Walsh, is now a vocal advocate for the bona fides of Team Sky. "He seems to have also gotten into the marijuana business recently... This guy was the harshest critic of everybody, right up until a British guy won, and then things were great."

Not everything is so different in 2016. The Phonak team disbanded in the wake of Landis' 2006 positive test, only to return three years later rebranded as BMC, but with the same owner, Andy Rihs, and much of the same management, including Jim Ochowicz. Ochowicz was a consultant to the old Phonak squad and is now the general manager at BMC. Phonak and its management have always denied any knowledge of Landis' doping during his time on the team. In 2010, Ochowicz told the New York Times: "I have no clue what went on. I wasn't a part of it."

"There's management and I respect those guys, and then there's Ochowicz. The fact that he's still in cycling should give you no hope that it will ever change. Write that down. That's all I have to say about that guy," Landis says.

"I think that's a good lesson for everybody. Look at what happened. The only people who ever got punished were the cyclists. And we now know with 100 percent certainty that all but a very few people in management positions were in on it, and nothing happened to them. If you want to make a judgement now about whether things are different, it's pretty simple deduction. You don't have to be a genius here, we don't need a fucking task force to figure out what happened. We don't have any reason to believe that the incentives have changed."

The effects of Landis' whistleblowing were eventually also felt in the UCI, where Pat McQuaid was replaced by Brian Cookson as president in 2013, though he scoffs at the notion that the Briton was elected on a mandate of change. "Cookson's been part of the establishment from the beginning. People will say we've changed things but Pat McQuaid didn't create the system either, and getting rid of one guy doesn't change it. Especially if you replace him with a guy who's been there the whole time as well," Landis says.

But then, as the IOC's reaction to evidence of state-sponsored doping in Russia is again showing, individuals rather than institutions tend to pay the price when the music stops. In 2012, there was a clamour to rebuild cycling even if nobody seemed to have a clear idea of what that blueprint should look like, not even the man who had so shaken the edifice in the first place.

"I don't know what the solution is," Landis says. "It's a mess to begin with, but at the very least, if you're going to have a set of rules, apply them consistently. But right now, it's improbable that you'll ever be caught in the first place. But whatever, just watch the Tour and see a nice castle on the side of the road and then some dude wins. Well, maybe he won or maybe he didn't, we'll find out ten years from now. It's just not a good approach to anything."

***

Even Landis' most withering assessments of the current state of cycling are delivered not with rancour, but with an almost detached, wry humour. Since Armstrong confessed in 2013, he has receded from the spotlight, bar an update on the status of his whistle blower case here and a Hollywood movie portrayal there, and his contact with the sport has been limited, which seems to be precisely how he wants it. David Zabriskie is his only close friend from his former milieu. "It's because he's a real person. I don't think he ever really fitted in cycling either and he sort of understood," Landis says.

Ahead of the Tour, however, Landis found himself in the news once again following the launch of his new business concern, Floyd's of Leadville, which specialises in vape and edible products containing cannabis oil. Recreational use of marijuana has been legal in Colorado, where Landis spends most of the year, since the beginning of 2014. "I'm happy to finally be involved in a legitimate industry," Landis wrote pointedly on Twitter after announcing the venture in June.

"Marijuana is equally as effective as prescription opiates and nowhere near as harmful socially, especially the addiction part of it," says Landis, though he is mindful of the stigma attached to his current line of work. "That's going to take a long time to change because everybody has this belief that it ruins society because that's what they were told in the 80s when the whole War on Drugs thing started. There are plenty of drugs in the world that do real harm, but they're prescription drugs and those guys have expensive lobbyists."

A man who doped as a professional athlete choosing to sell marijuana for a living was always likely to attract its share of gaudy headlines. One might think that Landis' experiences after 2006 had left him inured to derision, but he admits to feeling a degree of trepidation before making his venture public.

"My bigger concern would be what the reaction from the public would be. I don't go looking for ridicule, I don't like it," Landis says. "And I was concerned people would make some kind of judgment about it, but for the most part, the press has been good about it. Maybe it's just been a long enough time and there's not much left to say about the whole doping thing. That was kind of my concern. I don't like it, I don't like being ridiculed."

It's put to Landis that surely there is no such thing as bad publicity for a new business and he raises his voice with mock seriousness. "That's not true, that is not true," he says, shaking his head. "I am here to tell you: that's wrong."

***

Landis and his friends are still in the lobby of the Hyatt when André Greipel crosses the line two kilometres away on the Champs-Élysées to win the stage. His partner Alex and daughter Margaret, meanwhile, have spent the afternoon in the funfair in the Tuileries Gardens, and Landis smiles when he receives a message from Alex complaining that they have been effectively hemmed in there by the barriers in place for the Tour.

On the television screen, Froome, resplendent in yellow, takes a microphone and addresses the multitudes, the Arc de Triomphe shimmering in the background. The sound is still on mute, but nobody asks to turn it up. This recent tradition has its roots in Armstrong's "cynics and sceptics" speech after the 2005 Tour, though Landis recalls that no microphone was offered to him the following year, nor did he ask for one.

Another message from Alex informs Landis that she and Margaret are finally able to make their way towards them at Porte Maillot. It's getting towards time to find some dinner. "Come on," Landis says to his friends. "Let's go across the street and pick out a restaurant." Outside, it's already almost dusk. Landis will not make it to the Champs-Élysées until after the Tour has packed up and gone. But maybe that's only human.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.