Vuelta a España 2022 stage 15 preview - The hardest day

A GC battle on the daunting summit of Sierra Nevada

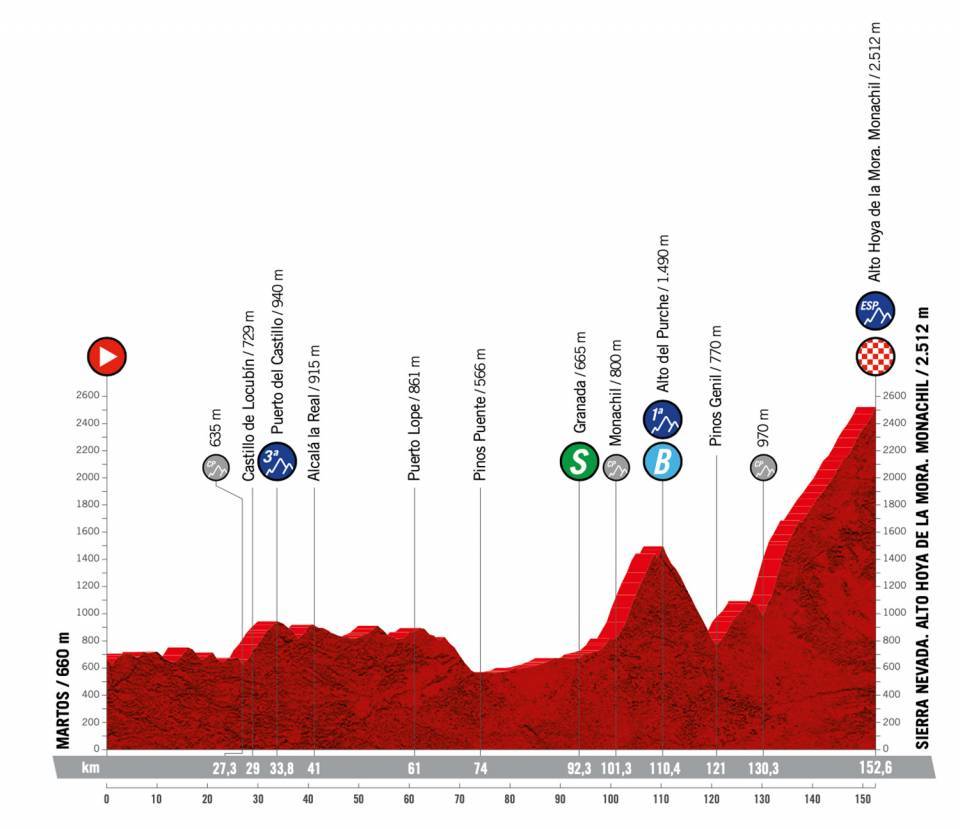

Stage 15: Martos - Sierra Nevada. Alto Hoya de la Mora. Monachil

Date: Sunday, September 4, 2022

Distance: 153km

Stage timing: 13:05-17:30 CET

Stage type: Mountain

It’s finally here. This Sunday the peloton face the long-awaited key mountain stage of the 2022 Vuelta a España to Sierra Nevada, the one widely rated as by far the single most difficult day of the entire race. And whatever happens in today’s [Sunday’s] stage, there can be no doubt it will mark the end of one major chapter in this year’s Vuelta and the start of another.

The reasons why the Sierra Nevada stage is so hard are multiple, starting with the altitude. Peaking out at 2,520 metres above sea level, when the riders ease round the final corner of the last climb leading to a windswept parking lot known as Hoya de La Mora, they will have reached the ‘ceiling’ of the 2022 Vuelta, and in fact stage 15 is the only one in this year’s race that finishes at higher than 2,000 metres.

Secondly, there's the sheer quantity of vertical climbing on this stage to handle. Calculated at just over 4,000 metres, this is greater than any other day on the Vuelta and most of it is packed into the last 50 kilometres as well. Thirdly, though it is forecast to be a relatively chilly 15 degrees at the summit of Sierra Nevada, the heat in the first flatter 100 kilometres, rising to around 35 degrees in the mid-afternoon, could well be another debilitating factor. Fourthly, Sierra Nevada has also been preceded by another difficult mountain stage to La Pandera, not to mention two full-on weeks of racing. At some point for every rider, the knock-on effect of all this is bound to be noted.

But in fact, the biggest challenge of the Sierra Nevada stage this year is that although the sixth summit finish of the 2022 race has previously been tackled 14 times in the Vuelta’s history and with multiple different routes to its summit, the 2022 variation on how the race will get to the top of Sierra Nevada is arguably the hardest ascent of them all.

The second the Vuelta riders reach the stage's main climbing finale at the Alto de Purche first category ascent at around km 101 of the 152-kilometre stage, they will start to appreciate that considerable difficulty for themselves. Rather than a gentle lead-in, as soon as the El Purche road leaves the mountain village of Monachil and curls back on itself to carve a path across the dizzily steep hillside above, it rears abruptly and cruelly from almost being flat to a 15% gradient. For the next four kilometres and as the road rises relentlessly, ramp after ramp of 13% to 15% on a completely exposed, stone-strewn landscape will test the riders' strength. This ascent is so demanding that by the time the peloton passed by the campsite that indicates El Purche’s first, ‘false’ summit, the brief respite that follows before the last, vicious, drag up to its definitive top will hardly be noticed in their legs.

Actually, the opening segment of yet another ascent road to Sierra Nevada, El Purche has witnessed some memorable racing moments in the past, both in the Vuelta a Andalucia, such as the ferocious duel between Alberto Contador and Alejandro Valverde in 2014, and in the Vuelta a Espana, where Cadel Evans saw his best chance of winning the race go up in smoke in 2009 following a painfully slow bike change by the neutral service vehicle.

This time round, El Purche will almost certainly provide the first sort out of the peloton, and the subsequent ultra-fast, twisting descent off the first category climb, with a couple of very dodgy corners in dense woodland, initially provides little opportunity for any dropped riders to get back on as well. It’s only when the route angles sharply back left and downwards to get onto the broad, fast, main Sierra Nevada road for a few kilometres that there could be some margin for the bunch to regroup.

But then the climbing starts all over again, only much harder. Following a sharp hook off the main road and perilously rapid single-lane descent to the town of Pinos Genil, a sharp left-hand turn takes the peloton onto the main climb of Sierra Nevada.

The only Hors Categorie ascent of the entire Vuelta, for some reason best known to the organisation, an initial six-kilometre grind on a winding mountain road past a large reservoir has not been officially included as part of the 20 kilometre climb. But as the peloton faces slopes varying between 8% and 10%, few riders in the bunch would probably agree with that decision.

Included on the ascent of north, part one of the final Sierra Nevada climb ends with a jaw-droppingly rapid, technical, corkscrew-like plunge down from the village of Guejar Sierra, all on a narrow, single-track road adorned with huge pennants saying ‘stage 15 Vuelta a Espana’ just in case anybody is worried where they’re heading. For a few blissful minutes of descending given what’s coming next, riders will likely reach the bottom of a narrow ravine at speeds of 80 or 90 kmh.

That speed will abruptly drop, though, as the route runs over a bridge, across a chicane then immediately begins the Hazallanas segment of the Sierra Nevada climb. This is perhaps not as hard as the 25% gradients of Les Praeres on stage 9, but in any case, Hazallanas remains extraordinarily difficult and is by far the single toughest section of the entire day’s climbing.

For around five kilometres, hairpin after hairpin of narrow, badly surfaced road rears upwards without any breaks. The average gradients of each corner are - kindly - provided on signboards on the side of the road: 18%, 19%, 18% again. At some points, though, Hazallana steepens still further, to around 22%. The message is clear: if an attack goes here and sticks, there are few opportunities to turn the tables and no hiding places at all.

With about three kilometres to go to the summit of the Hazallanas segment of Sierra Nevada, the road becomes a lot straighter and the gradient eases considerably and the final part, whilst rising steadily, is no longer as difficult. The principal challenge at this stage in the game could be both the increasingly high altitude, plus the very treacherous road surface. Certainly, just like Les Praeres, team support will almost be irrelevant by this point: rather Sierra Nevada will be an individual challenge.

How hard is it?

So how hard is it? Perhaps appropriately, as Cyclingnews could see on a recon on Saturday morning of the Hazallanas, there was surprisingly little road graffiti on this part, except a series of messages daubed in support of British climber Hugh Carthy (EF Education-EasyFirst). Certainly the Briton will find the slopes of Hazallanas to be nearly as steep as the more notorious Angliru, where he took his biggest win to date in the 2020 Vuelta a España.

However, there’s a crucial difference to the Angliru. When the grimly steep slopes of Hazallanas peter out shortly before linking up with the broad, main road up to Sierra Nevada, the ascent is scarcely halfway over. Rather after the 8 kilometres of Hazallanas, and 6 kilometres of approach road before that, on Sunday there are still another 12 kilometres of climbing to go.

Riders suffering badly can perhaps take some consolation that unlike what was originally planned (and as still figures in the route book), the Vuelta’s idea of going up the old approach road to the top of Sierra Nevada had to be dropped for ecological reasons. Rather the bulk of the final part of the 2022 Sierra Nevada ascent will be on the broad, exposed highway leading to the debatable architectural charms of Pradollano ski station.

While the Hazallanas was where Chris Horner placed a significant downpayment on his 2013 Vuelta win overall, the upper slopes of Sierra Nevada, if notably easier, have also seen some major moments in the Vuelta as well. Just to cite a couple, the summit of the climb saw how Laurent Jalabert, who dominated the race, decided to gift the win to longstanding breakaway Bert Dietz, in 1995. Then in 2011 Sierra Nevada also witnessed the first world-class level Grand Tour mountain performance of a certain Chris Froome in the 2011 Vuelta. At that point in the Vuelta, of course, Froome was working for Bradley Wiggins, but finally in fact Froome was able to take the win for himself.

“That part of Sierra Nevada is a smooth climb on a broad road, but it’s very steady, that’s for sure, too,” observes race co-designer Fernando Escartin to Cyclingnews. “So if a gap has opened up on Hazallanas and a rider is isolated, it’s really tricky terrain to pull back those kinds of gaps."

“The wind is going to be a massive factor," former pro Nicolas Roche, now a cycling TV commentator, told Cyclingnews about the same climb in 2017 when Miguel Angel Lopez won the stage. "The last part of the climb, above the ski station, makes for a big difference between a tailwind and a headwind.” “Training on it, I could be doing 15, 16 kilometres an hour with a headwind and with a tailwind, 25 kilometres an hour. So if there's a headwind, you'll have to be sure you're not isolated and can hang in with a group, otherwise you're going to shed time very fast."

After four or five kilometres of continuing remorselessly upwards on the ski station road on gradients of roughly five percent, the broad A-road swings round gradually to the left and the ski station of Pradollano, perched well below the peaks of Veleta and Mulhacen, looms into view. But if any of the riders think reaching the ski station could represent the end of the day’s climbing torture, they’d be sorely mistaken.

Instead, just where the main reaches the outskirts of Pradollano, at a small roundabout the route lurches left and more steeply uphill again. The road is equally wide and well-surfaced, but the gradient doubles to around eight percent for a good kilometre.

For any GC contenders, this last ‘ramp’ may be much easier than the Hazallanas segment, but opportunities for climbers to attack other than here are running out. That’s because when the road emerges out of a small pinewood and hooks back right to run along the summit of a ridge, for all there are five kilometres left to race, the gradient has lessened again, notably. More than the toughness of these final, exposed, slopes, then, it could be the altitude and accumulated exhaustion could be taking their toll.

The only really testing moment of this final part of the climb comes in the last few metres, where the road doubles back and rears more sharply skywards, well within sight of the Vuelta's finishing gantry. But by then any damage inflicted by the climbers on the remainder of the field will either have taken effect or it will be way too late to make a difference.

And if the challenge of the hardest ever ascent of Sierra Nevada has taken a toll, it was close to going on for even longer. The riders probably won't see them but 50 metres further on from the finish, two barriers block the road on a partly tarmacked route leading towards the summit of the Pico Veleta. The Vuelta organisers wanted, originally, to end the race some 300 metres higher, thus claiming the bragging rights of the highest ever summit finish in a Grand Tour. But as that part of the Sierra Nevada wildlife park does not permit the entrance of motorized vehicles, it didn't happen.

So what could happen on Sunday in Sierra Nevada? Given the events of stage 14 where Remco Evenepoel suffered his first bad day on the Vuelta, to say that the race leader is guaranteed to remain in control of the GC all the way to Madrid after Sierra Nevada would be unwise in the extreme. But as set piece challenges go, Sierra Nevada is certainly the most demanding stage of them all, so whoever has the red jersey resting under their pillow on Sunday night, the race will be theirs to lose.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.

Latest on Cyclingnews

-

Amazon Prime Day bike deals: The sale is almost finished, this is your last chance to grab yourself a deal

Don't hang around, Amazon Prime Day is coming to an end but there are still some great deals available -

Where's the beef? The UAE-Visma Tour de France rivalry is intense but respectful so far

"UAE and Visma are perhaps the strongest teams but only one can win," says Mauro Gianetti -

'I wonder how they recover like that every day' – Mathieu van der Poel loses yellow jersey at Tour de France as Grand Tour fatigue sets in

Dutchman more than satisfied with performance in first seven stages despite getting dropped on return to Mûr-de-Bretagne -

'I don't know if I'm getting any closer to that win' – Oscar Onley best of the rest behind Pogačar and Vingegaard on Tour de France stage 7

World champion says young Scot has 'showed in the past already how a superb rider he is, with a punchy kick' after third place at Mûr-de-Bretagne