Mighty Ventoux set for Tour's final battle

Never in the history of the Tour has the Giant of Provence been given such a pivotal role. Cyclingnews looks back at the history of Tour visits to the spartan summit.

Never before has the legendary Mont Ventoux appeared so late in the Tour de France, and never has it been as decisive for the overall classification as it will be come Saturday when the race finishes at its summit on the penultimate stage.

Absent in the Tour de France for seven years, it was last the scene of Frenchman Richard Virenque's solo triumph and one place where Lance Armstrong further cemented his fourth Tour victory.

Standing 1,912 metres tall in the Provence region of southern France, the Mont Ventoux has been visited by the Tour 13 times, seven as a summit finish and six in passing during a stage. It will be the third and final mountain top finish of the 2009 Tour de France, the final obstacle of the 167-kilometre penultimate stage.

It is a mountain known for its bald, limestone summit absent of vegetation and with unrelenting wind - the mistral has been recorded at speeds in excess of 320 km/h - and during Tour stages, its usual oppressive heat.

Many chapters of Tour de France heroism and heartbreak have been written on Mont Ventoux, and the Tour organisers are expecting that the 2009 Tour's outcome will still be in doubt until the Ventoux has been conquered.

Coming from Montélimar, the peloton will pass through olive country near Nyons and hit the hilly hinterland of the mountain from its Northern side. A loop eastwards will then see the riders tackle the non-classified Col de Notre-Dame des Abeilles before they hit the final climb from its traditional, most difficult side starting in Bédoin.

The peloton will face an unrelenting 21.1-kilometre ascent averaging 7.6 percent that ends at the rocky scree of a summit which will lay the fortitude of our yellow jersey contenders as bare as its lunar-like landscape.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Before one can predict who will emerge victorious atop this Giant of Provence, we must first dig deep into the history books to see how previous battles on this climb have unfolded.

1958: Stage 15, Bédoin-Mont Ventoux (21.5km time trial)

A Tour de France stage would end at Mont Ventoux's summit for the first time in 1958, the year Luxembourg's climbing and time trialing phenom Charly Gaul would achieve his only Tour victory. And while Gaul didn't attain the maillot jaune on the slopes of the Ventoux, he would make a dramatic move up the GC with his dominating win.

Gaul, who started the day ninth overall, 10:41 behind Italian Vito Favero, would end the day within striking distance of the new leader, France's Raphaël Géminiani. Gaul moved into third behind Géminiani and Favero, who finished 24th, 7:59 slower than Gaul.

Only one man, Spain's "Eagle of Toledo", Federico Bahamontes, would finish close to Gaul at 31 seconds, but he was no threat overall. The remaining 91 riders would all cede minutes to Luxembourger, who, despite preferring cooler weather, still excelled in the scorching conditions that day. He would ultimately prevail by 3:10 over Favero and 3:41 ahead of Géminiani when the race finished.

Mont Ventoux was the second of three time trials that year, all won by Gaul. The Luxembourger cemented his place in Tour lore and legend by also winning the 219-kilometre stage 21 from Briançon to Aix les Bains in apocalyptic rain, beating the nearest finisher by nearly eight minutes, fully negating the ten minutes he lost due to a mechanical incident the day after his Ventoux triumph.

Gaul's time of 1:02:09 for the 21.5-kilometre ascent of Mont Ventoux would stand as the record for nearly 41 years until Jonathan Vaughters set a new best time in winning the third stage of the 1999 Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré, a time trial along the same course from Bédoin to the Mont Ventoux summit, in 56:50.9.

Iban Mayo, the Basque Euskaltel-Euskadi climber, set the current record in the 2004 Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré's stage five time trial, ascending the Giant of Provence in 55:51.49.

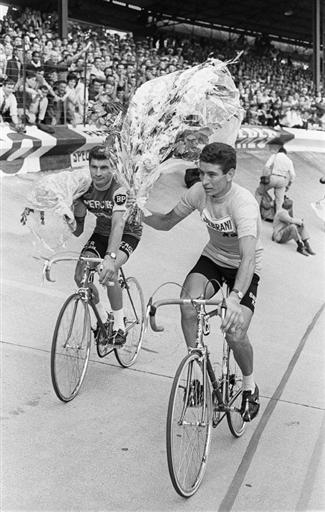

1965: Stage 14, Montpellier-Mont Ventoux (173km)

France's beloved Raymond Poulidor, "the eternal second", finished on the Tour podium eight times in his career, thrice second and five times third, and never wore yellow for one day of the 14 Tours he started.

On paper, 1965 should have been Poulidor's year to triumph in the absence of arch-rival Jacques Anquetil, but nobody expected 22-year-old Italian Felice Gimondi, in his first year as a professional, to capture his solitary Tour victory.

However, Poulidor drew great satisfaction from his triumph on Mont Ventoux during which he moved into second place overall and reduced his GC deficit to only 34 seconds behind Gimondi. Poulidor bested Spain's Julio Jimenez, who he had been in a break with for much of the stage, by six seconds.

Gimondi made a superhuman effort to close the gap to Poulidor to 1:34 on the day, finishing in fourth place.

"Felice Gimondi took quite some time from me in the first part of the Tour that year. In the mountains I was able to distance him but it wasn't possible to make up all the time on him," Poulidor told Cyclingnews.

"That day, I won on the Mont Ventoux ahead of [Julio] Jimenez and Gimondi was in difficulty. He was able to restore the situation to his advantage in the end, and finally won the Tour de France. But the Mont Ventoux that day was part of my greatest victories, it was a revelation."

Poulidor commented on what makes Mont Ventoux such a special fixture in professional cycling. "You climb it from the south side, during a very hot season, in the beginning of the afternoon. It's practically a desert! There is no vegetation, nothing... the heat is unbearable, you can't breathe.

"The finish on top of the Ventoux is the finish of the stage, so you've already made considerable efforts beforehand in the stage. There had been attacks of those who thought they might have a chance to win...there is no time to recover."

Poulidor is particularly looking forward to watching Saturday's stage, where the Ventoux will see tired riders tackle this climb to the finish. "This year, it will be especially hard. It was a very good idea by the organiser to put the Ventoux practically at the end of the race.

"We will have three or four potential winners that day - one at the foot of the climb, another one halfway up, yet another one with three kilometres to go and the final winner in the finish! That would be absolutely extraordinary!

"Everything is possible that day. If there are three or four overall favourites within one minute of each other - or even more - nothing will be decided until the very last metres of the climb."

1970: Stage 14: Gap-Mont Ventoux (170km)

It should come as no surprise that Belgian legend Eddy Merckx would make his mark on the slopes of Mont Ventoux during his storied career. Merckx wore yellow for all but three days of the 1970 Tour, including the final 18 in a row, and won eight stages en route to beating runner-up Joop Zoetemelk by 12:41 and Sweden's Gosta Pettersson by 15:54 for his second Tour victory.

Going into the Tour's 14th stage to Mont Ventoux Merckx already held a commanding 6:39 advantage over Zoetemelk while Pettersson's deficit stood at 10:42, but Merckx being Merckx he stamped his authority on the race yet again, leaving all in the peloton behind amidst the suffocating heat on that July 10th.

Merckx's former teammate Martin Van den Bossche would finish closest, 1:11 behind, while Pettersson, in 9th place, lost a further 1:39 to the Cannibal and Zoetemelk ceded 2:47 to finish in 15th place.

The victory did exact a toll on Merckx, however, as his pedalling become rather erratic in the closing several hundred metres of the stage. While walking to the podium Merckx fainted and received oxygen in a nearby ambulance before stepping to the stage.

In a poignant moment approaching the stage's finish, Merckx tipped his hat while passing the memorial to deceased English professional Tom Simpson two kilometres from the Ventoux summit just as Tour de France race director Jacques Goddet was leaving a bouquet of flowers at the memorial.

Three years earlier, Merckx was a teammate of Simpson on Peugeot-BP-Michelin (although not a competitor in the 1967 Tour), the year Simpson died on the slopes of the Ventoux, and was the only professional cyclist to attend his funeral.

Merckx would be the only cyclist to ever win a summit finish at Mont Ventoux while wearing the yellow jersey.

1972: Stage 11: Carnon-Plage - Mont Ventoux, (207km)

It was something of a minor miracle that Bernard Thévenet was even in the Tour de France on stage 11 after being part of a brutal crash in the Pyrenees on stage 7. While pursuing Merckx on a descent in wet, treacherous conditions, Luis Ocaña crashed taking Bernard Thévenet, Lucien Van Impe and Alain Santy down as well.

Thévenet received a concussion and temporarily lost his memory. According to Vélo he looked down at his Peugeot jersey and wondered whether he might be a cyclist and upon recognizing the team car, he said, "I'm riding the Tour de France!"

Four days later, however, Thévenet soled to victory on Mont Ventoux, beating race leader Eddy Merckx by 34 seconds and Luis Ocaña by 39 seconds.

Eddy Merckx would win his fourth consecutive Tour in 1972, while Thévenet would have to settle for ninth overall, 37:11 behind, plus stage wins on Mont Ventoux and one week later in Ballon d'Alsace. Thévenet would win his first Tour five years later in 1977.

1987: Stage 18: Carpentras-Mont Ventoux (36.5km time trial)

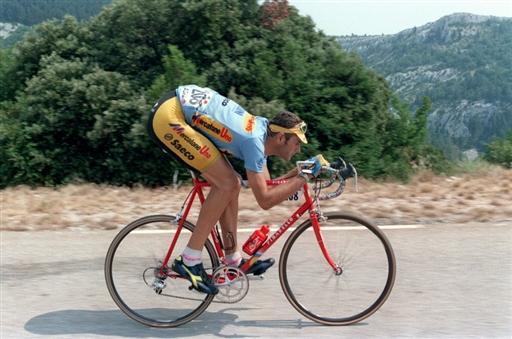

Jean-François Bernard's masterful time trial victory on Mont Ventoux propelled the 25-year-old Frenchman into the yellow jersey and into the hearts of France, but his stint in yellow the following day would be the only stage in which Bernard would ever wear yellow throughout his career.

Bernard raised some eyebrows while seen warming up on his low-profile time trial bike for a mountain time trial, but his Toshiba-Look directeur sportif Paul Koechli had a plan in mind. The opening 15 kilometres of road rose at a very gentle gradient from Carpentras to the beginning of Mont Ventoux 's climb, so Bernard would start on his time trial bike to gain an aerodynamic advantage before switching to his road bike to complete the 21.1-kilometre ascent to the summit.

Bernard rode like a man possessed to Mont Ventoux's summit past a crowd estimated at 400,000 people, stopping the clock at 1:19:44. Admitting afterwards that "I felt terrible", nonetheless Bernard beat the cream of the Tour's climbers with Colombia's Luis Herrera 1:39 behind in second place while Spain's Pedro Delgado finished third, 1:41 back.

Bernard beat Stephen Roche, the fifth place finisher, by 2:19 and bested race leader Charly Mottet by a hair less than four minutes.

Bernard now led Roche by 2:34, Mottet by 2:47 and Delgado by 3:56, but would finish the next day's stage 4:16 behind Delgado and Roche due to an untimely puncture and turn over the yellow jersey to the Irishman.

Bernard would finish the Tour on the podium for the only time in his career, in third behind Roche and Delgado, having won two time trials along the way. 1987 was Roche's magical year: he became only the second rider in history to win the Giro, the Tour and World Championship in a single season. The first, of course, was Eddy Merckx.

2000: Stage 12: Carpentras-Mont Ventoux (149km)

When the peloton reached Bédoin with only the 21-kilometre ascent of Mont Ventoux remaining, a nine-rider break held a two-minute advantage over the peloton. As the chasing field approached the sharp left-hand bend in St. Esteve that signaled the start of the steep section of Mont Ventoux, US Postal Service had taken over the chase.

First Tyler Hamilton, then Kevin Livingston did yeoman's work up front for Lance Armstrong, while behind, José Maria Jimenez (Banesto), Alex Zülle (Banesto), Fernando Escartin (Kelme) and Christophe Moreau (Festina) simply dropped off the intense pace of the front runners on the wooded forest road.

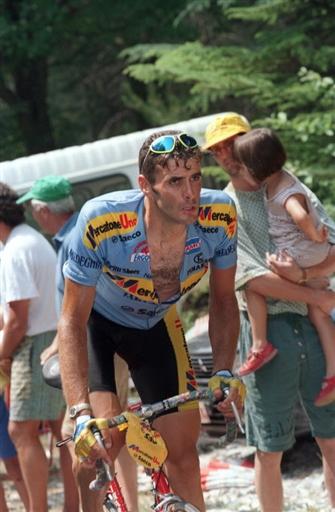

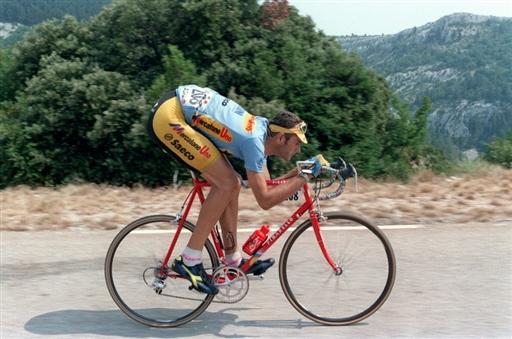

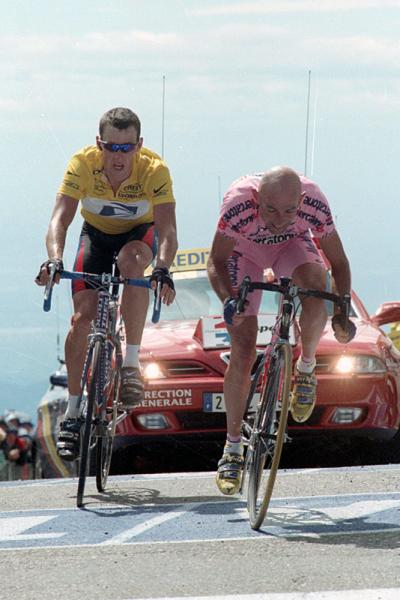

With 10 kilometres to race, the front group had been whittled down to six, composed of Armstrong (USPS), Roberto Heras and Santiago Botero (Kelme), Richard Virenque (Polti), Joseba Beloki (Festina) and Jan Ullrich (Telekom), with Marco Pantani (Mercatone Uno-Albacom) yo-yoing off the back of this group.

Ullrich made most of the tempo going up, and when the steep Ventoux climb leveled out a bit at Chalet Reynard with 6.5 kilometres to go, Pantani made it back to the front group for good.

Chalet Reynard is just above the tree line on Mont Ventoux, at 1410 meters above sea level, and it's where the riders are exposed to the full force of the fierce mistral wind. Suddenly Pantani attacked, his acceleration visibly hurting the other leaders, notably Richard Virenque, who went out the back almost immediately.

Pantani attacked three more times and eventually got a gap with 3 kilometres to race. Armstrong, the maillot jaune, attacked from the rear of the group to chase Pantani and made contact with 2.5 kilometres left to the line. Armstrong and Pantani rode away from the elite chase group and at the summit the Italian nosed ahead of Armstrong to claim victory, 33 years to the day after Tom Simpson died on the Ventoux's slopes.

But did Armstrong "gift" Pantani the stage? A war of words would forever strain relations between the two champions about the circumstances surrounding Pantani's victory and the theme "no gifts" would become an Armstrong mantra in future Tours.

2002: Stage 14: Lodève-Mont Ventoux, 221km

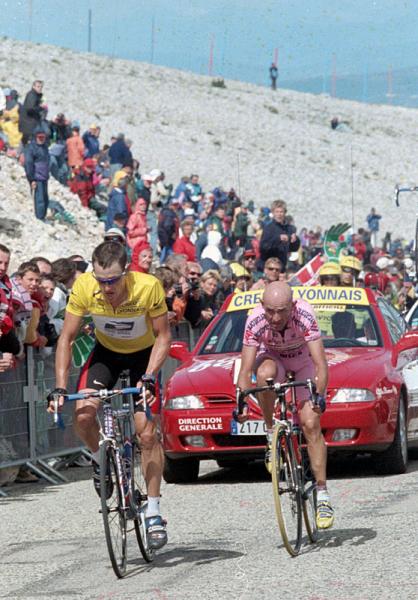

Richard Virenque would etch his name into the legends of Mont Ventoux seven years ago when he arrived at the summit nearly two minutes ahead of Russia's Alexandre Botcharov and 22 seconds more in front of race leader Lance Armstrong.

Virenque went long that hot July Sunday, situating himself in an 11-man break which went clear only 19 kilometres into the 221-kilometre stage. The escapees attained a maximum advantage of 12:03 over the US Postal Service-led peloton and arrived at the foot of Mont Ventoux with a lead of nearly seven minutes.

With nine kilometres remaining to the summit, Virenque dropped Botcharov, the Frenchman's last remaining companion from the day-long break, while Armstrong found himself without teammates in a group containing the ONCE duo Joseba Beloki and José Azevedo, Lithuania's Raimondas Rumsas, Italy's Ivan Basso (leader of the best young rider classification) and Spain's Francisco Mancebo.

Emerging from the scrubby pine woods at Le Chalet Reynard into the lunar last stretch up to the finish with 6.5 kilometres to go, the struggling Virenque had 4:00 on the Armstrong group. Beloki attacked on a steep pitch 1 km before Le Chalet Reynard and Armstrong quickly pounced on the ONCE rider's wheel, then turned the tables on Beloki and counterattacked him hard. Armstrong dropped the Basque, decisively demonstrating just who was the boss of the 2002 Tour de France.

As Armstrong set a savage tempo. One kilometre up the road with four kilometres remaining, Virenque was hanging on to a 3:50 advantage on the surging Texan, while Beloki was desperately chasing in the desolate treeless, lunar landscape.

As he did the previous year winning Paris-Tours, despite his damaged reputation, Virenque was showing his class, suffering mightily as he heaved himself upwards to the Ventoux summit. With 3 kilometres to race, Virenque still had 2:00 on Botcharov, with Armstrong coming up fast. The top three would remain in that order at the finish, with Armstrong extending his GC lead over second place Beloki and third place Rumsas.

Returning veterans

Twenty-seven members of the 2002 peloton will return to the 2009 Tour de France, most notably, of course, being Lance Armstrong. Only three other 2009 Tour starters cracked the top 20 the last time the race climbed the Mont Ventoux.

Levi Leipheimer (who unfortunately abandoned the Tour prior to Mont Ventoux) finished 11th, 4:25 behind Virenque. Stéphane Goubert, currently with AG2R La Mondiale, finished in 13th at 5:25 and Cofidis' David Moncoutié finished right after in 14th at 5:46.

Lance Armstrong is the only member of the 2009 Tour's top 10 to compete in the 2002 Tour. Carlos Sastre, who currently sits in 15th on GC, finished Mont Ventoux seven years ago in 29th place, 8:37 behind Virenque. Sastre would ultimately arrive in Paris in 10th place that year, the only rider other than Armstrong in the 2009 Tour peloton to crack the top 10 in 2002.

Just what will transpire on Saturday's penultimate stage is still anyone's guess, but perhaps one can gleam some sort of precedent from past visits to the Giant of Provence.

Will a Luxembourger with an impeccable climbing pedigree stamp his authority on the barren slopes?

Can a Frenchman once again capture the attention of his home nation with a dramatic victory?

Will the maillot jaune stamp out the hopes of all pretenders to the throne with one final, emphatic victory before his coronation on the Champs-Élysées?

Are there any Italian climbers able to sprint to victory by the Ventoux Observatory?

Will a certain Texan reclaim a gift given in error nine years ago?

Or perhaps another American, Christian Vande Velde, can, as director Jonathan Vaughters puts it, "pull off the win of his life"? No matter what the outcome, it's certainly to be a worthy addition to the history of Mont Ventoux.

In addition to Mont Ventoux being a summit finish on seven occasions, the Tour de France has passed over Mont Ventoux a further six times.

Three times prior to the first summit finish in 1958, the Tour ventured over the Giant of Provence.

The first man to ever crest the summit of Mont Ventoux in the Tour was the Greek-born, naturalised Frenchman Lucien Lazarides during 1951's stage 17.

Lazarides would finish seventh on the stage, 56 seconds behind winner Louison Bobet, but would ultimately arrive in Paris on the podium in third place.

One year later in 1952, Frenchman Jean Robic reached the Ventoux summit first in the 178-kilometre stage 14 and would push on to win alone by 1:37 over an elite seven-man chase group led by Gino Bartali and containing the likes of Raphaël Géminiani, 1952 Tour runner-up Stan Ockers and 1952 Tour winner Fausto Coppi.

1955 Tour winner, Frenchman Louison Bobet, was the first over Mont Ventoux on the 198-kilometre stage 11, winning his second stage of the Tour. Bobet would have to wait six more days before assuming the maillot jaune and ultimately claiming his third consecutive victory, the first time a rider claimed three straight Tours.

What was perhaps most memorable, and disturbing, about that hot Monday's transverse of Mont Ventoux was the collapse of Jean Malléjac, who was sitting eighth overall at the day's start, 10 kilometres from the Ventoux summit.

Malléjac lapsed into a state of semi-consciousness, his eyes rolled back into his head and the race doctor had to pry open his jaw to administer first aid. Malléjac was forced to abandon, but fortunately recovered from the harrowing incident, denying that doping was the reason for his collapse.

The event foreshadowed the tragedy which fell upon the next passing of Mont Ventoux, on July 13, 1967, the day which Tom Simpson died on its slopes.

The tragedy which will forever be synonymous with the Giant of Provence.

Spaniard Julio Jimenez was the first to reach the summit of Mont Ventoux during the 211.5-kilometre stage from Marseille to Carpentras won by the Dutchman Jan Janssen, but the day will be forever remembered as the day Simpson collapsed three kilometres from the Ventoux summit.

The race doctor tried for 40 minutes to revive Simpson on the roadside. He was taken by helicopter to hospital in Avignon, but could not be revived.

A memorial to Simpson stands approximately two kilometres from the summit of Mont Ventoux.

In 1974 Eddy Merckx would win his fifth Tour de France, and during stage 12's 231-kilometre journey from Savine-le-Lac to Orange the unheralded Spaniard Gonzalo Aja crested Mont Ventoux first while Belgian Jozef Spruyt, a teammate of Merckx, claimed stage honours. Aja would finish fifth to Merckx that year, 11:24 behind the Belgian.

One of the most memorable ascents of Mont Ventoux in Tour de France history occurred in 1994, the year Italian gentle giant Eros Poli broke away early in the 231-kilometre fifteenth stage from Montpellier to Carpentras.

Poli arrived at the base of Mont Ventoux with nearly a 25 minute lead over a complacent peloton and needed virtually all of those minutes to drag his 6'4" frame up the 21.1-kilomtre ascent in the race lead.

Poli, a gold medalist in the team time trial at the 1984 Olympics and a force in Mario Cipollini's lead-out train, had a physique totally at odds with rapid climbing, and he managed to lose one minute per kilometre as he made his painful, weaving ascent to the Ventoux summit.

Poli prevailed, however, still maintaining a couple of minutes at the Ventoux summit, and put his physique to better use plummeting off Mont Ventoux to achieve a most epic solo victory in Carpentras, 3:39 ahead of the day's second-place finisher.

Based in the southeastern United States, Peter produces race coverage for all disciplines, edits news and writes features. The New Jersey native has 30 years of road racing and cyclo-cross experience, starting in the early 1980s as a Junior in the days of toe clips and leather hairnets. Over the years he's had the good fortune to race throughout the United States and has competed in national championships for both road and 'cross in the Junior and Masters categories. The passion for cycling started young, as before he switched to the road Peter's mission in life was catching big air on his BMX bike.