Giro d'Italia 2021: Five key stages

The far side of the Zoncolan and a tappone for the ages

There is rarely a straightforward day on the Giro d’Italia, with potential pitfalls painted into just about every panel of the route. The 2021 edition continues in that tradition. With some 47,000 metres of total climbing on the route, there are obstacles littering the gruppo’s path all across the peninsula, as they make their way from Turin down to Foggia and then back into the high mountains in the final week.

As ever, the mighty passes catch the eye – most notably, the extreme tappone on stage 16 – but the modern Giro doesn’t limit its difficulties to the biggest mountains or the obvious set pieces. Some rugged days across the Apennines in the opening 10 days have the potential to create early drama – at Guardia Sanframondi on stage 8, for instance, or at Campo Felice the following afternoon.

Much depends, too, on the approaches of contenders like Egan Bernal (Ineos Grenadiers), Vincenzo Nibali (Trek-Segafredo), Thibaut Pinot (Groupama-FDJ), Emanuel Buchmann (Bora-Hansgrohe), Dan Martin (Israel Start-Up Nation) and Remco Evenepoel (Deceuninck-QuickStep), but even at this early remove, some key stages stand out.

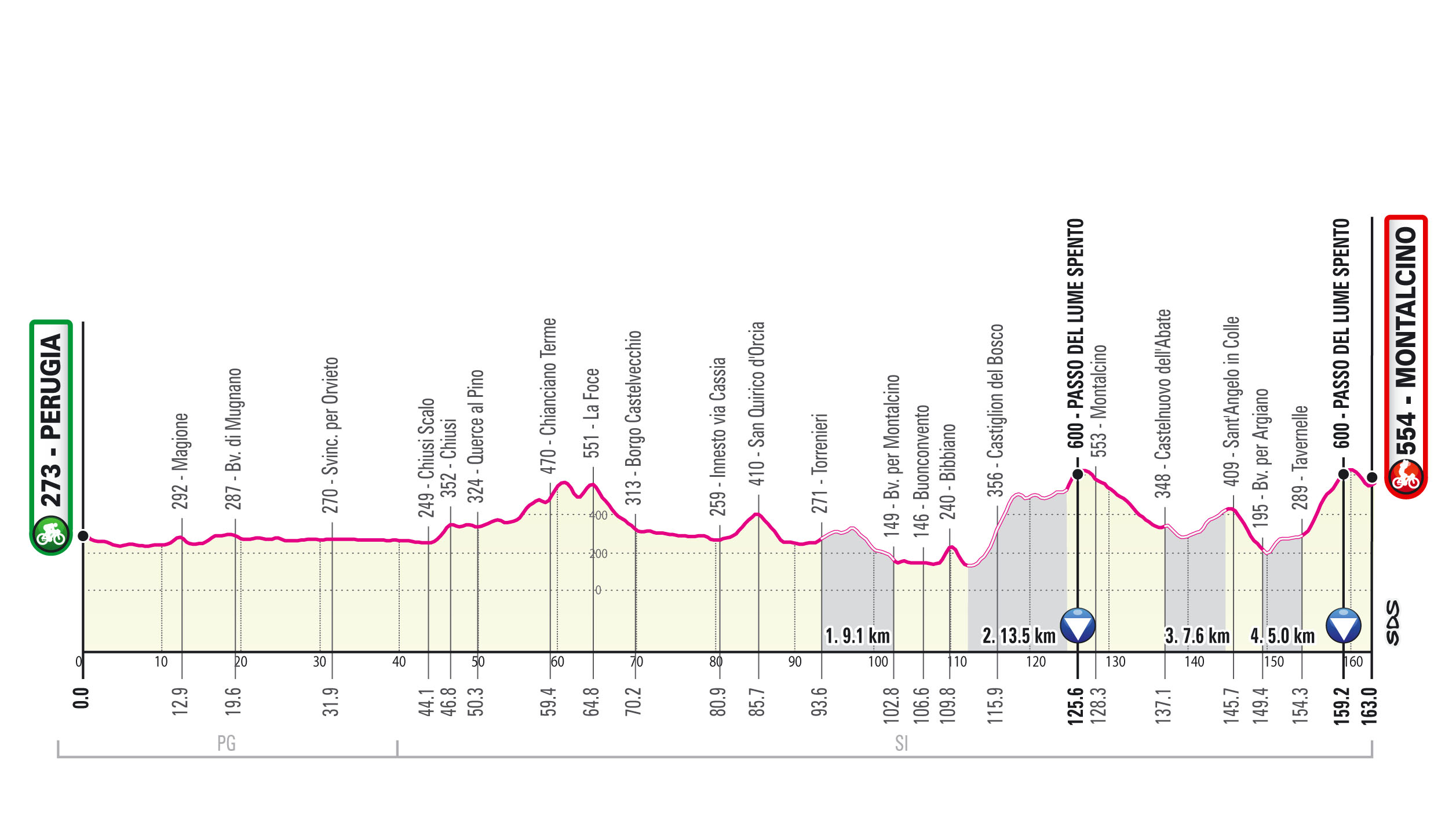

Stage 11: Perugia – Montalcino, 163km (May 19)

The Giro’s last visit to the gravel roads around Montalcino in 2010 provided one of the defining stages of its modern era, with Cadel Evans emerging victorious on an afternoon of torrential rain, his rainbow bands barely visible beneath a coating of mud.

The (re)discovery of gravel in the 21st century has changed the bicycle industry at large, but 11 years ago the sight of pro riders on gravel was still a real novelty. The Giro had forayed tentatively onto gravel on the Finestre in 2005 and Plan de Corones in 2008, and RCS Sport, inspired by l'Eroica Gran Fondo, had also launched in 2007 what is now Strade Bianche.

But perhaps nothing served to popularise the concept of gravel racing for a wider audience quite like that miniature epic to Montalcino. It was a day that confirmed there was a future in throwing back to the past. Even the Tour de France has since followed in the Giro’s wheel tracks, adding gravel sections at La Planche des Belles Filles and the Plateau des Glières in recent years.

In 2010, the Montalcino stage featured 14km of strade bianche across two sectors in the final 20 kilometres. This time out, the gravel sectors expand to four, and they make up some 34km of the final 70km of the stage.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The first, 9.1km sector at Torrenieri is followed by the longest and most demanding sector, which takes in the stiff climb of Castiglion del Bosco and totals 13.5 kilometres. After cresting the summit of the Passo del Lume Spento, there already will be plenty of lights out in the gruppo, but there is further hardship to come. Two more rippling sectors of gravel (7.6km and 5km in length, respectively) follow ahead of another ascent of the surfaced Passo del Lume Spento, this time from a different approach. The first man to the top will be in the box seat to claim victory in Montalcino three kilometres later.

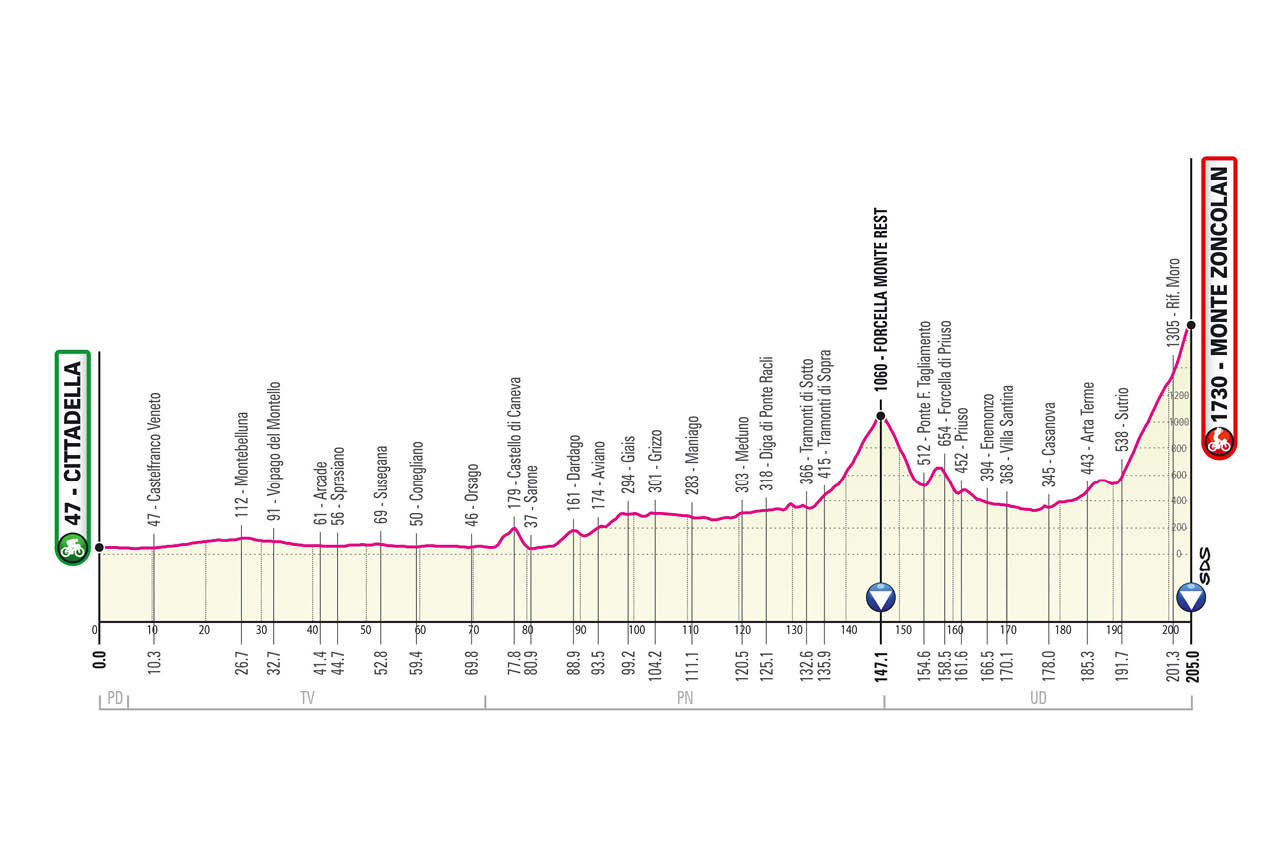

Stage 14: Cittadella – Monte Zoncolan, 205km (May 22)

While the Zoncolan always helps to define the Giro, it has rarely proved decisive, given that its extreme steepness can also limit the size of the gaps at the summit. After all, even the strongest riders can only go so fast when their front wheels are touching their noses.

This time out, however, the Zoncolan offers a different challenge, given that the Giro returns to the ‘easier’ approach from Sutrio, not used since the race’s first visit in 2003. It’s all relative, of course, given the gradient hits 22 per cent in the final kilometre, but this will require a slightly more nuanced, tactical approach than the familiar grind from Ovaro, where the only real strategy is to battle gravity and maintain momentum.

The ascent from Sutrio is 13.5km in length with an average gradient of 9 per cent but, crucially, it is a climb of two parts. The opening 9km are something akin to the Mortirolo, with slopes that are steep but not to excess. The average gradient is a stiff 8.7 per cent, but unlike the Ovaro ascent, there is some respite, with a section of false flat of 1500 metres or so.

The false flat is also a false dawn, as the road kicks up viciously in the final 3.5km, where the average gradient is 13 per cent and there are several sustained stretches in excess of 23 per cent. This version of the Zoncolan caused consternation in 2003, when Gilberto Simoni was first to the top, and on its competitive debut on the 1997 Giro Rosa, when Fabiana Luperini emerged victorious.

The Zoncolan’s fearsome reputation has traditionally dissuaded GC contenders from testing one another on the preceding climbs and that trend should continue here, even if the route takes in the Forcella di Monte Rest, site of Stephen Roche’s famous ambush on the 1987 Giro. The Sutrio side of the Zoncolan is certainly different, but that doesn’t mean it will feel any easier.

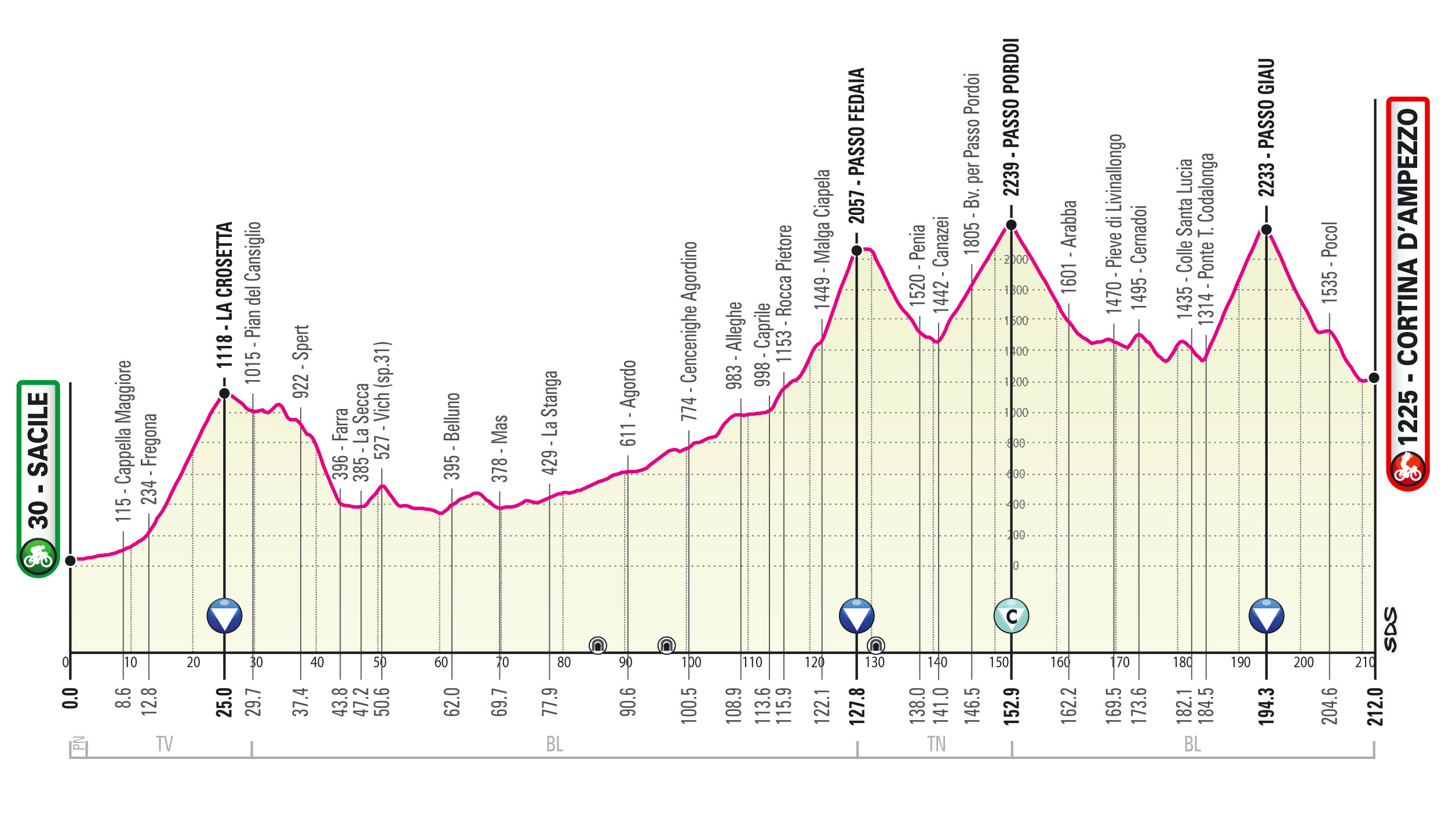

Stage 16: Sacile – Cortina d’Ampezzo, 212km (May 24)

Dislivello 5,700m. At first glance, it looks like a misprint, tucked away in the corner beneath the profile of stage 16, but it’s true. When the cycling season ground to a halt last spring, ‘Everesting’ enjoyed its moment in the sun. Now in 2021, Mauro Vegni proposes something akin to the Giro’s take on the concept. This mammoth leg to Cortina d’Ampezzo takes in some 5,700 metres of total climbing, which amounts to almost two thirds of the altitude of Mount Everest.

Vegni explained that he had made a conscious decision to limit the Giro’s trips to extreme altitude in 2021, but there are still three ascents above 2,000 metres on road from Sacile, as the route takes in the Passo Fedaia, Passo Pordoi and Passo Giau with next to no respite in between.

“This is the tappone of the Giro,” Vegni said on Wednesday, as if there were any doubt. “It takes in some of the epic mountains of cycling.”

The day’s first ascent to La Crosetta the easiest, but the climbing begins more or less from kilometre zero. Cruelly, the road also drags unremittingly upwards for a long time even before the beginning of the Passo Fedaia proper, which is the first instalment in the race’s three-part trek through the Dolomites.

The Fedaia, which lies at the base of the Marmolada, brings the 2021 Giro above 2000 metres for the first time. The ascent has not featured on the Giro in a decade and is perhaps best renowned as the launchpad for Marco Pantani’s offensive in 1998. After a descent to Canazei, the road climbs immediately towards the Passo Pordoi (12km at 6.9 per cent) staple of the Giro since 1940. Fausto Coppi was first to the top on no fewer than five occasions in those early years, establishing its switchbacks as something close to hallowed ground. As the highest point of this year’s Giro at 2239m, it will be the site of the Cima Coppi prize.

The final part of the Dolomite triptych is the Passo Giau, which begins with ramps of 12 per cent and never really relents, with an average gradient north of 9 per cent. On cresting the summit, riders face a rapid 18km from the finish in Cortina d’Ampezzo, though there are enough technical sections to pose problems for tired minds. Tough mountains stages can often intimidate to the point of discouraging aggressive riding, but the extremity of this tappone means that substantial time gaps appear guaranteed.

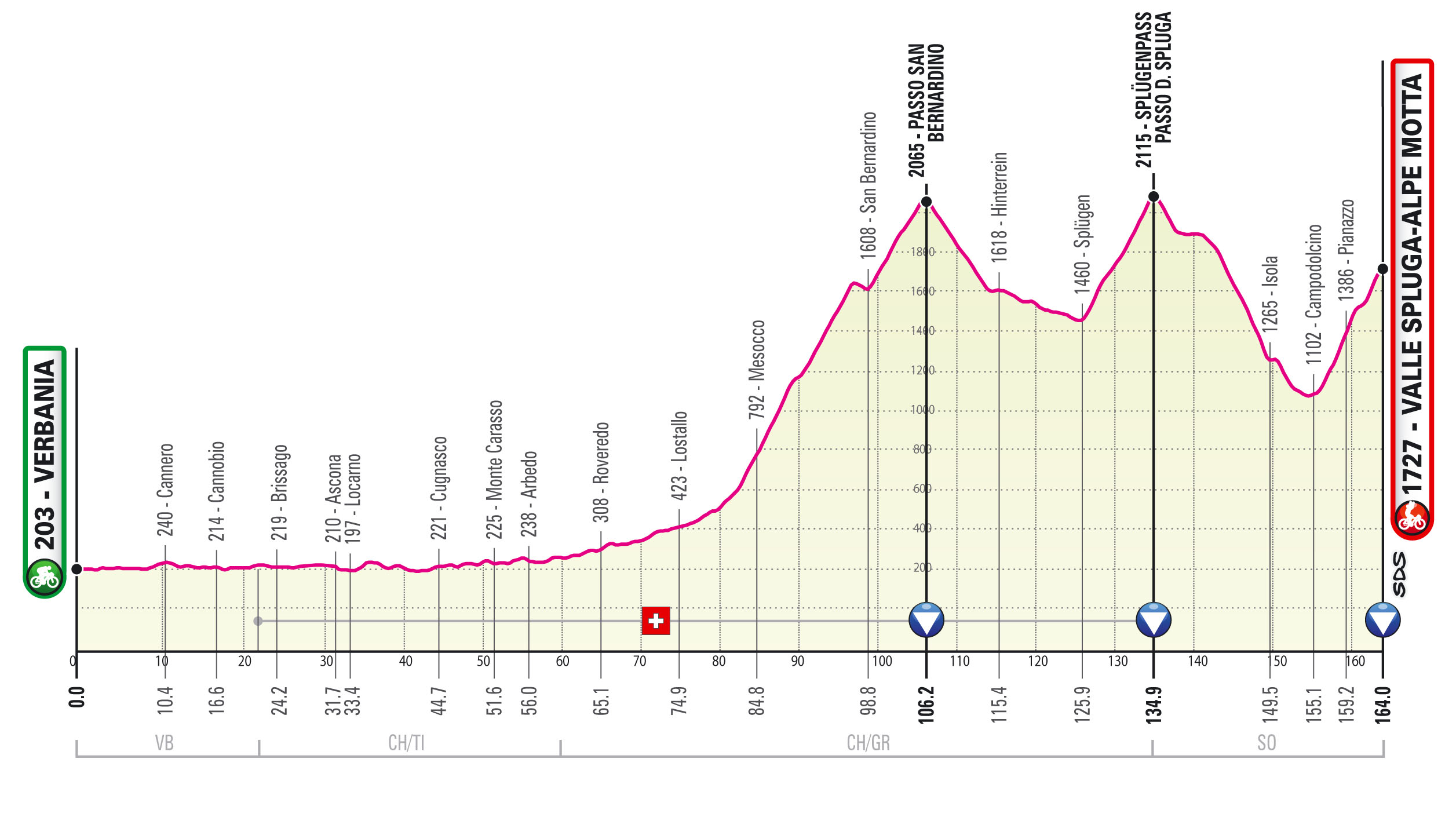

Stage 20: Verbania – Valle Spluga-Alpe Motta, 164km (May 29)

As per tradition, the bulk of the Giro’s mountain stages feature in the final third of the race, though they are not packed as tightly together as one might ordinarily expect. The Dolomite tappone on stage 16 is followed by a rest day, while the summit finish at Sega di Ala on stage 17 precedes a flat but strikingly long run from Rovereto to Stradella.

Back-to-back mountain stages eventually arrive in the Giro’s final days. After climbing the Mottarone and a summit finish at Alpe di Mera on stage 19, the gruppo must cross from Verbania into Switzerland for perhaps the second toughest stage of the entire race, with some 4,700m of total climbing.

After leaving Filippo Ganna’s hometown of Verbania, the route hugs the shore of Lake Maggiore as it plots a flat course to the Swiss border. The climbing begins shortly before the midpoint of the stage, with the Passo di San Bernardino dragging on for a seemingly interminable 30 kilometres.

On cresting the 2,065m-high summit, the road drops to Splügen and the base of the short but wickedly steep Passo dello Spluga, which hasn’t featured on the Giro since 1965, when Vittorio Adorni was first to the top. The summit marks the Italo-Swiss frontier and the race descends into the Italian side of the Valle Spluga. Early rumours suggested the stage would finish in the village of Madesimo, but instead the road climbs one more time, taking in the new ascent of Alpe Motta, which gives this Giro its eighth summit finish.

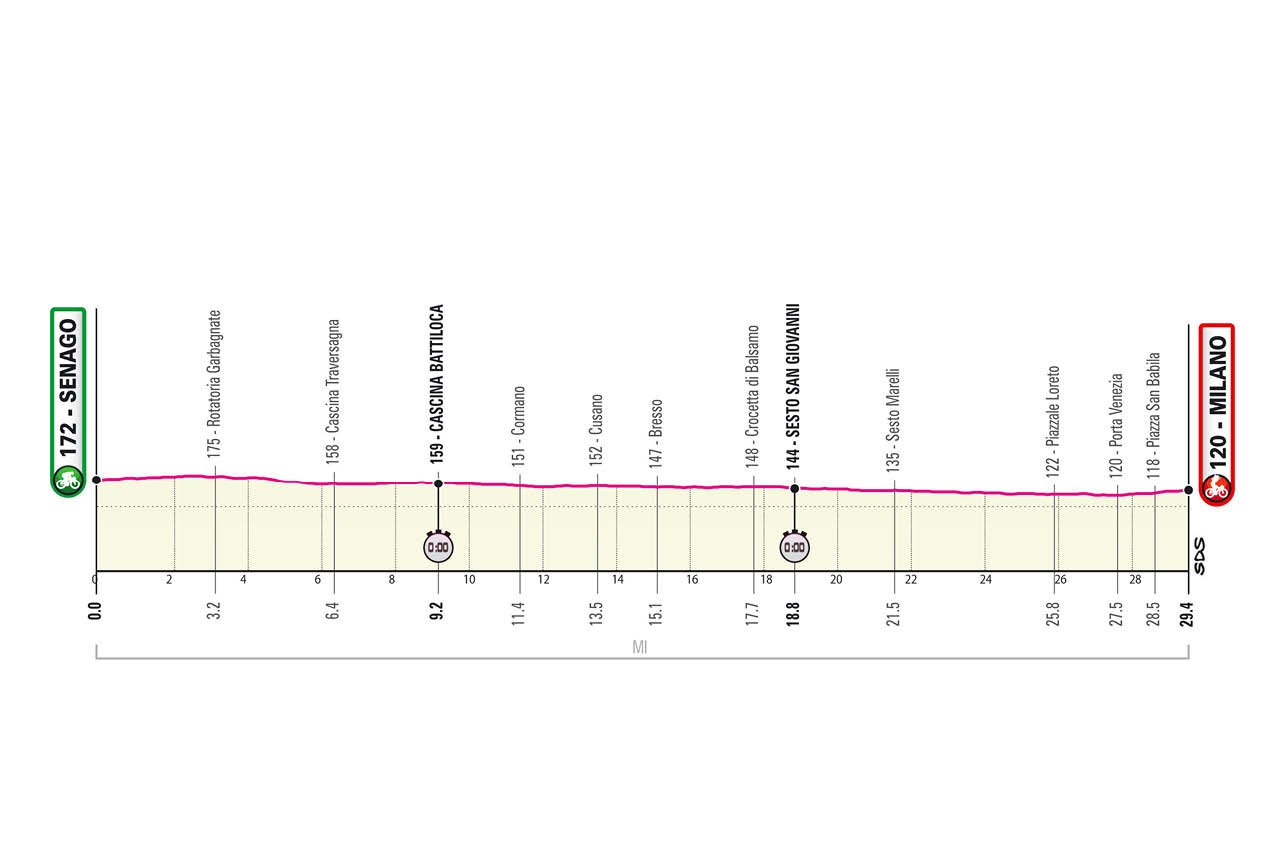

Stage 21: Senago – Milan, 29.4km individual time trial (May 30)

When the 2020 Giro route was unveiled, one wondered if the 16km final time trial to Milan would serve as a low-key epilogue to such a mountainous route. Instead, the short test effectively served as a tie-breaker after 3,345.2 kilometres of racing had failed to separate Jai Hindley and Tao Geoghegan Hart by so much as a second.

It remains to be seen if the concluding time trial will play as pivotal a role in May, but at almost twice the length, there is certainly scope for significant changes in the overall standings in the final chapter of this Giro.

It’s true that a third week time trial rarely if ever provokes the same gaps as an equivalent test earlier in the race, but in modern cycling, a few miles against the watch can still add up to an enormous difference in the final reckoning. The 2017 Tour de France was a case in point. Romain Bardet managed to fare better than Chris Froome across the mountains on that race, but he still finished 2:20 off the pace in third after conceding 2:35 to the Briton in just 36km of total time trialling.

Together, the opening and closing day time trials of the 2021 Giro account for just 38.4km, or a little over 1.1 per cent, of the total distance. Logic says the 47,000 metres of total climbing should suffice to decide the race, but the maglia rosa has changed hands after similar (and shorter) Milanese time trials in the recent past: Geoghegan Hart divested Hindley a year ago, Tom Dumoulin took the jersey from Nairo Quintana in 2017, and Ryder Hesjedal snatched victory from Joaquim Rodriguez in 2012.

As ever, the Milan time trial course is flat and fast. There are some early twists and turns en route to Sesto San Giovanni, before the route straightens out on the final approach to the city. On current form, world champion Filippo Ganna is, even at this remove, the unbackable favourite to claim stage victory in Piazza Duomo, but his effort might yet be a mere footnote to a dramatic finale in the overall contest – particularly if Remco Evenepoel recovers in time to make his Grand Tour debut.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.