Major Taylor led the way for Black athletes in professional sports

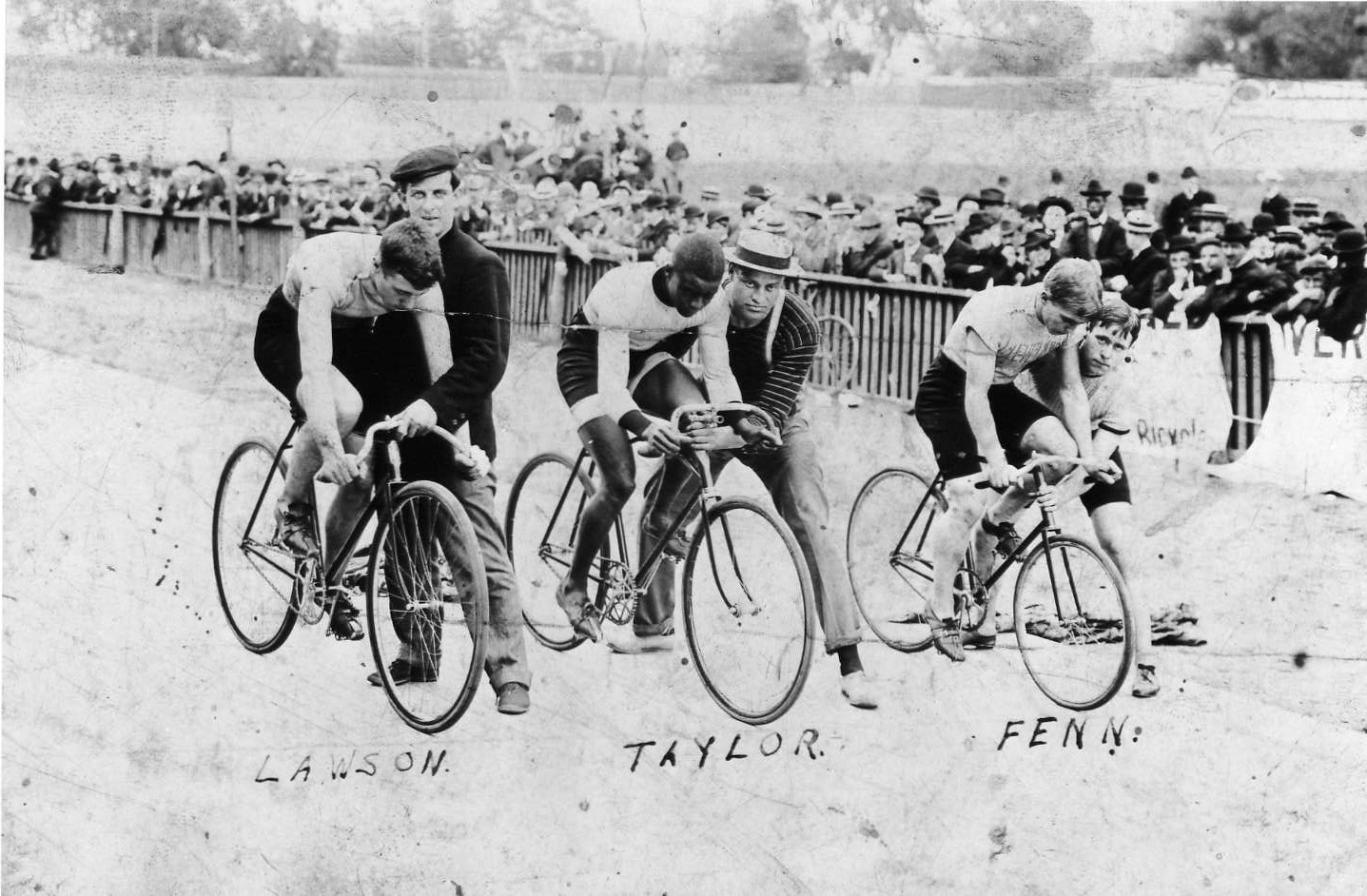

A photo of Taylor offers insights into American cycling in 1901

In August 1901 Marshall "Major" Taylor of Indianapolis arrived by train in Newark, New Jersey after a campaign that spring as a match sprinter in Paris and other destination cities around the Continent. He had won 42 of 57 races he started against national champions on their home velodromes, including France's world champion Edmund Jacquelin.

Taylor's early season earned him more than $10,000 in prize money and appearance fees, worth $310,000 today—and far greater than Major League Baseball stars, like Honus Wagner pitching for the Pittsburgh Pirates, earned that year.

Taylor lined up at the Newark Velodrome in this photo, never published in his lifetime. He sat between Iver Lawson, a Swedish immigrant and naturalized U.S. citizen living in Chicago, on the outside, and Willie "Boy Wonder" Fenn, Sr., from Waterbury, Connecticut, on the pole. They rode scratch, behind a dozen pros staggered ahead on the track, to begin a ten-mile handicap race.

More than 10,000 onlookers filled the grandstand and cheap seats. Hundreds of others stood on the infield, including Black men in suits and stylish bowler hats like bankers, joining the rail birds.

Taylor, 22, reigned as America's national professional sprint champion from the previous season, based on points awarded in the National Cycling Association summer series of races from the quarter-mile to the mile. He had won the 1899 world sprint championship in Montréal – only the second Black athlete, following Canadian boxing champion George Dixon winning the 1892 bantamweight boxing title, ever to claim a sport's world title.

At the turn of the 20th Century, basketball was a new sport spreading like a rising tide from Northeast college campuses to the South and Midwest. Football drew as much interest as badminton. Major League Baseball remained racially segregated until Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers (today's LA Dodgers) as a first baseman in 1947.

America was fraught with racial segregation. Douglas A. Blackmon in his Pulitzer Prize-winning Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II observes that the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court ruling of "separate but equal" in Plessy v. Ferguson sanctioned contemptuous attitudes of Whites toward Blacks.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Taylor lived and raced as much for the challenge of testing himself against rivals as to show audiences that he had chain lightning in his legs and a tactical mind for winning as sharp as anyone. He specialized in match sprints over a mile, or a kilometer, pitting one rider against another to see who could hit the finish line first on the home straight in front of the grandstand. Promoters built two-hour programs with events culminating in the match sprints.

"In a word I was a pioneer, and therefore had to blaze my own trail," Taylor wrote in his self-published autobiography, The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World.

Taylor recounts battles he had beyond the muscle-burning, lung-bursting effort of all-out pedaling. One rider he had defeated got off his bicycle, grabbed Taylor by the neck, and choked him. Some promoters refused to allow Taylor to start a race after they had invited him there at his expense. Many restaurants around the country had staff that refused to serve him. Yet in his autobiography he remains gracious. "There will always be that dreadful monster prejudice to do extra battle because of their color."

Rather than settle old scores, Taylor in his book writes: "Life is too short for any man to hold bitterness in his heart."

He didn't live long enough to know that Jackie Robinson integrated Major League Baseball. But the Supreme Court's 1896 separate-but-equal ruling remained in effect and continued to reinforce racial segregation in Robinson's career.

Holding Taylor in this photo is his personal trainer, William Buckner, who had accompanied Taylor in his spring tour. Buckner would become an athletic trainer for the Chicago White Sox in 1910, one of the rare Black athletic trainers in racially segregated MLB.

Taylor rode an Iver Johnson bicycle, for which he was paid $1,000 – now worth $31,000. Made in Fitchburg, Massachusetts, Iver Johnson frames were equipped with an innovative underslung curved top tube, designed make the diamond frame more rigid.

On his right, Iver Lawson rode under contract for Cleveland Bicycles, made in Chicago. Lawson grew so frustrated from losing NCA national sprint championships to Taylor and then to Taylor's rival and fellow Hoosier, Frank Kramer of Evansville, that in 1904 Lawson shipped out on his own across the Atlantic to the world championships in London. Lawson dethroned defending champion Thorvald Ellegaard for the world title.

Holding Lawson is his older brother, John, known as "The Terrible Swede" for pedaling over a rider who had fallen in front of him in a six-day race. In the following winter, John Lawson would die of pneumonia.

This photo came from Fenn, a first-year pro at age 20. He had turned pro after winning the 1900 NCA national amateur championship. On the start line, Fenn rode a special motor-pace bicycle, with a standard 28-inch rear wheel and an 18-inch front wheel that lowered his center of gravity. His bicycle was made by George Pierce in Buffalo, remembered for his Pierce Arrow automobiles that became iconic in the 1920s Jazz Age. Holding Fenn was William Collett, a pro from New Haven.

Fenn's lower center of gravity may have aided him as he led the pursuit of the handicappers. Fenn won by edging Taylor at the finish line.

For the rest of the season, Taylor gamely competed in NCA championship races but he couldn't make up for missing points lost during the spring he spent in Europe. Frank Kramer, who had lost the title to Taylor in 1900, beat him in points for the 1901 title.

A week after the photo was taken, Fenn won a five-mile handicap race and set a new world record: 10 minutes and 33.4 seconds. He settled in Newark. When he retired in 1905, he operated a corner gas station.

His son, Willie Fenn Jr., succeeded him as the 1924 NCA national amateur sprint champion, competed that year in the Paris Olympics, and turned professional.

Taylor died in 1932, age 53, the same age as Jackie Robinson, who died in 1972.

Peter Joffre Nye is author of the second edition of Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing (University of Nebraska Press). He serves on the board of the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame.

Peter Joffre Nye is author of the updated second edition of Hearts of Lions: The History of American Bicycle Racing (University of Nebraska Press).