Gravel’s too serious, so I built a fixed gear bike for a 200km gravel race

Trying to keep the spirit of gravel alive, one gear at a time

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

What started as an alternative niche, gravel has rapidly grown over the last decade and, for better or for worse, the gravel racing scene has become increasingly more serious. Events have grown in stature, with more eyes and more money than ever, and it's now attracting some of the biggest names in cycling. Brands have been quick to jump on the bandwagon too, and the start line of any prominent race on the gravel calendar has become awash with some serious tech.

With racing now extremely competitive and rules still relatively lenient around innovation, riders are doing everything they can to squeeze every ounce of performance from the best gravel bikes, resulting in all manner of bleeding-edge tech on show at events like the Traka and Unbound. For the tech nerds, it's a proverbial smorgasbord, but for most everyday riders who aren’t hunting the marginal gains for their gravel ride, it can all become a bit clinical, obsessive and boring.

I can’t blame racers for being racers, but the pursuit of performance at all costs attitude does somewhat fly in the face of what gravel originally stood for. Many hours can be spent sharing tales of adventures or plotting new adventures through unknown territory with your fellow gravel rider, but it's harder to bond in the same way over CdA or which gravel tyres are the fastest.

The term ‘spirit of gravel’ makes me cringe, mostly due to its liberal use by marketers and influencers; however, it represents the foundations of gravel: inclusiveness, community and, most importantly, having fun on a bike. When gravel riding started to become popular, it was the closest thing you could get to a fringe anti-mainstream subculture while still wearing lycra.

It wasn’t dissimilar to the bike messenger scene, a hodgepodge of riders and bikes coming together to embrace diversity, individuality and a DIY attitude. Nothing was taken too seriously, and although competition is a fundamental part of a lot of bike riding, it wasn’t so important that you couldn't stop for a beer mid-race. Could you imagine the racers of Unbound stopping to sit on a chaise lounge mid-race these days?

Like any popular sub-cultures, gravel was destined to become mainstream, and while that's not a bad thing — it’s fueled huge innovations that have made gravel bikes better than ever — it does erode some of the qualities that attract so many riders to the scene in the first place.

Just to be clear, this isn’t a slight at mass adoption or gravel racing. The more people riding bikes, the better, and competition is a fundamental part of keeping the sport alive. Whether racing is in your repertoire or not, the evolution of gravel racing plays an important role in the development of the genre and the overall scene, too.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

I won't ever be jostling for position in the front pack of a gravel race, so I have little need to bore myself with marginal gains. I still like the idea of taking part, though, soaking in the vibe with my fellow gravel riders whilst putting myself to the whip to see what I can achieve. With an entry to the Dirty Reiver secured in Spring, I had an itch to build a new gravel race bike for a very specific purpose.

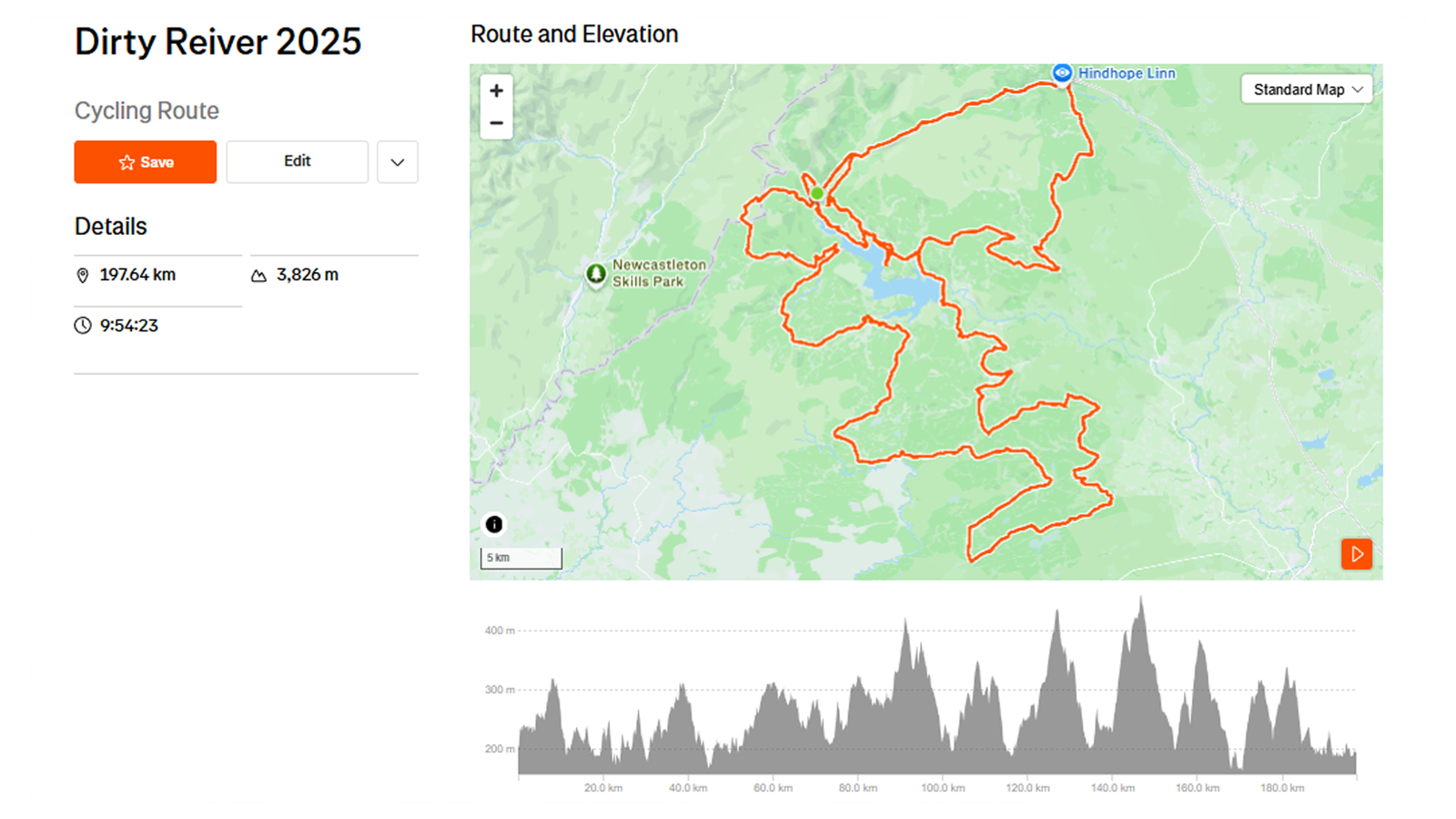

For those who don’t know about the Dirty River, it's the UK’s biggest gravel event and most akin to the famous American gravel grinders that really kick-started the gravel race scene. The 196km Kielder Forest route is almost entirely on gravel too and while the punchy rolling terrain sees the total elevation stack up quickly, most of those metres are relatively easy come by. I have ridden this event many times too, so I’m well acquainted with the route.

This wouldn’t be another gravel race super build, though. I wanted to put together a bike that would stand out from the crowd and might rekindle the spirit of gravel in the hearts of some of my fellow gravelleurs. In a scene where everyone seems to be riding the best of the best, the bells and whistles become boring. I had to come up with something different. As Graeme Obree once said, “You can always add something to your bike, but you’ll get to a point where you can’t subtract anything else, and that’s a fixed gear.”

This wasn’t a complete leap into the unknown. I've completed the Dirty Reiver on a fixed gear before, although my previous finishing time of 8 hours 30 minutes feels quite far off my sub-eight-hour goal. I had previously ridden my old faithful Surly Steamroller, with its heavy steel frameset and MTB handlebars; however, by building the ultimate gravel race fixed-gear bike, I should unlock significantly more than marginal gains.

Riding 200km of gravel on a fixed gear probably sounds like a dreadful undertaking to most riders, especially when you factor in the 3100m of climbing accrued as the course wiggles its way around the Kielder forest. My goal wasn’t just to complete the 200km distance; I wanted to do it in under 8 hours. So, although I was going to be riding a silly bike, it would have to be a fast silly bike.

The first aim of the build was to find a suitable frameset. The main checklist points were to find something lighter than the Steamroller, which cleared at least a 40mm tyre and fit a front disc brake. I also wanted to use traditional 120mm track spacing, which really narrowed the options down.

Skream Bikes is a small fixed gear brand from Hong Kong and its Ranger tracklocross frameset ticked all the boxes. If you thought fixed gear gravel was niche, tracklocross is a whole other level and involves racing track bikes on a cyclocross-style course. The Ranger is a fixed gear bike designed specifically for off-road riding and, despite its svelte 120mm rear end, has a quoted tyre clearance of 43mm at the rear and a disc brake fork. Most importantly, the 6066 T6 Triple Butted Alloy Tube Frame and full carbon fork are reasonably light too, saving more than a kilogram compared to the all-steel Surly setup.

The geometry is pretty interesting too, even when compared to the current crop of gravel race bikes, it's aggressive with a long top tube, low stack and 72 degree head angle. The seat tube is relatively steep, too, at 75 degrees. This suits me as my default saddle position is usually as far forward as the saddle rails will allow. Finally, the 57mm bottom bracket drop is notably high for good reason, offering plenty of clearance to pedal through corners.

The main reason behind wanting a traditional track chain line was ease of setup. A proper 144bcd track crankset paired with a dedicated fixed gear hub will ensure a perfect chain line. It does add a bit of weight, but I think it's worth it, plus a 1/8th track chain should be a little more sturdy when ripping high-speed gravel skids on the descents. The Rotor Aldhu track crankset, with its solid aero spider, fits the build perfectly. I opted for a 165mm crank arm and sized down to a 46t chain ring to give me more gear ratio flexibility.

Gear ratio is obviously going to have a massive impact on speed, so there was a lot to consider, as I obviously wouldn’t have the luxury of shifting gears during the ride. The ratio has got to be easy enough to grind your way up the hills, but not so spinny that it rips your legs off on the descents. You also need to be wary of skid patches, as some chainring and sprocket tooth counts will quickly result in a single bald patch on your tyre. I wanted to keep the gear ratio as similar to my tried and tested 48x21t (2.29 gear ratio) setup, but as I was moving from 650b to 700c, I would need to effectively gear down to account for the larger wheel diameter.

Unsurprisingly, it's uncommon to find track sprockets in larger tooth counts. A few years ago, it was pretty easy to get hold of a 24t sprocket, but all my usual sources seem to have dried up. Dropping the chainring size to 46t meant I could run a more easily attainable 21t sprocket for a gear ratio of 2.19 and a healthy 21 skid patches.

The last big part of the puzzle was sourcing a set of gravel wheels. Although speeds would be slower than a geared bike, I still wanted a wheelset that would provide some aero performance. It would also need to be pretty durable, as it's hard to finesse a bike through rough gravel sections when you can't stop pedalling. You will be shocked to hear that there are zero off-the-shelf fixed gear aero gravel race wheelsets on the market, so I would need to have a custom set built. Despite being a bit last-minute, The kind folks at Hunt sourced a Paul hub and laced it up with their 40 Limitless rim for me. The wheelset features front and rear specific rims, each with a wide rim profile and a 4.5mm bead thickness that would help fend off potential punctures.

I’ve heard good things about Panaracer’s X1 gravel tyres and have been keen to give them a go as I was a big fan of the venerable GravelKing SK ever since riding my first Dirty Reiver on a set back in 2018. I decided to push my luck with the tyre clearance and spec 45mm tyres. The Panaracer and Hunt combo blew up closer to 47mm, luckily, they still fit between the chainstays. Clearance was very tight, but as long as it wasn't too muddy, there wouldn't be a problem.

Finally, due to this build coming down to the wire, most of the finishing kit was sourced from the parts bin and scavenged from other bikes. I had hoped to save some more weight with an integrated cockpit and carbon post, but ran out of time once I had narrowed in on my fit. It may seem odd to specifically mention a drop bar when talking about gravel bikes, but having previously used a riser bar for extra control, it was a big change moving to a gravel handlebar to promote a more aero position. I had an Easton EC70 AX carbon bar that fitted the bill, pairing it with GRX levers and front brake calliper, with a 160mm rotor. A Thomson Masterpiece seatpost was sourced from my track bike and that had to be matched with a Thomson X4 stem, which was pilfered from my town bike. Selle San Marco, along with Panaracer, sponsors the Dirty Reiver, so it felt fitting to spec its Shortfit 2.0 Racing saddle.

The finished build tipped the scales at 8.3kg, which might seem a bit heavy for a gravel bike that doesn’t have a derailleur, cassette or rear brake. However, considering it has an alloy frame, deep and wide wheels, and big tyres, it's actually pretty decent. Most importantly, the 1.5kg overall saving against my Surly Steamroller should be very noticeable when grinding up the hills.

How did the ride go?

I'm not exaggerating when I say this build came down the wire. I didn’t get my hands on the wheels until the evening before the race. Even the best laid plans go awry, and unfortunately, the Paul hub that had been sourced had a 130mm axle, rather than 120mm. Luckily, I had brought spare wheels so I could still ride, although it did mean all my careful considerations around gear ratios and tyre size were out the window.

Did I achieve my sub-8-hour finish time? Not even close, I didn’t even improve on my previous time. However, I can’t blame the bike. My spare wheelset was 650b, so it dropped my gear ratio a bit too low, and near the end, a problematic puncture saw me haemorrhage time as the hole in my tyre first didn't want to seal and then refused to reseat onto the rim.

The only solace was that if there was a fixed gear category, I would have finished in first place, in a competitive field of one.

Ultimately, it was the doing, not the result, that was important. It would have been great to beat my previous time, but I still had a brilliant day out on the bike. In otherwise quiet groups, cheers of encouragement would burst out as riders spotted me grinding slowly up climbs or wildly spinning down descents. My masochistic choice of bike broke the ice, and it served as a launching point to chat with my fellow riders on the trail, at the feed stops, and after the finish line. While the fast boys treated their legs with post-race rituals and turned in for a night of recuperative rest, I stayed up drinking beers around the fire with my new friends, sharing stories from the day into the early hours of the morning.

Despite the now serious exterior of gravel events, my silly fixed-gear gravel bike showed me that underneath the stony-faced gravel racing façade, the spirit of gravel is still bubbling away; it just needs a little encouragement. For most of us mortals, we aren’t competing for the top spots; these events are about challenging ourselves and enjoying the experience. So rather than getting your head down for 200km and offering little more than a side eye or an elbow flick to your gravel comrades, let's dial back the seriousness because it really is more fun when you engage with the riders around you. I’m already signed up for the next one and now equipped with my go-faster wheels, maybe 2026 will be the year I achieve my sub-8-hour goal. If I do, it definitely won’t come at the expense of a mid-race beer.

Graham has been part of the Cyclingnews team since January 2020. He has mountain biking at his core and can mostly be found bikepacking around Scotland or exploring the steep trails around the Tweed Valley. Not afraid of a challenge, Graham has gained a reputation for riding fixed gear bikes both too far and often in inappropriate places.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.