Giro d'Italia – Carapaz and Hindley face final mountain duel on 'infinite' Fedaia

Dolomite stage offers last chance to break deadlock before Verona time trial

Five and a half kilometres from the top of the Passo Fedaia, at a place called Malga Ciapela, the gradient stiffens, the road straightens out and time seems to slow down. For the next three kilometres, there is no respite from the mountain. The tarmac rises interminably before the riders, without so much as a bend in the road to provide a distraction from the effort ahead.

That corridor is something equivalent to cycling's Strait of Magellan, a place where so many Giro d'Italia dreams have been tossed, blown and sunk over the years. This year, as the Fedaia returns for the first time since 2011 (dismal weather forced its removal from the 2021 route), the mountain arrives just as the race is reaching the shore, a day before the finish in Verona.

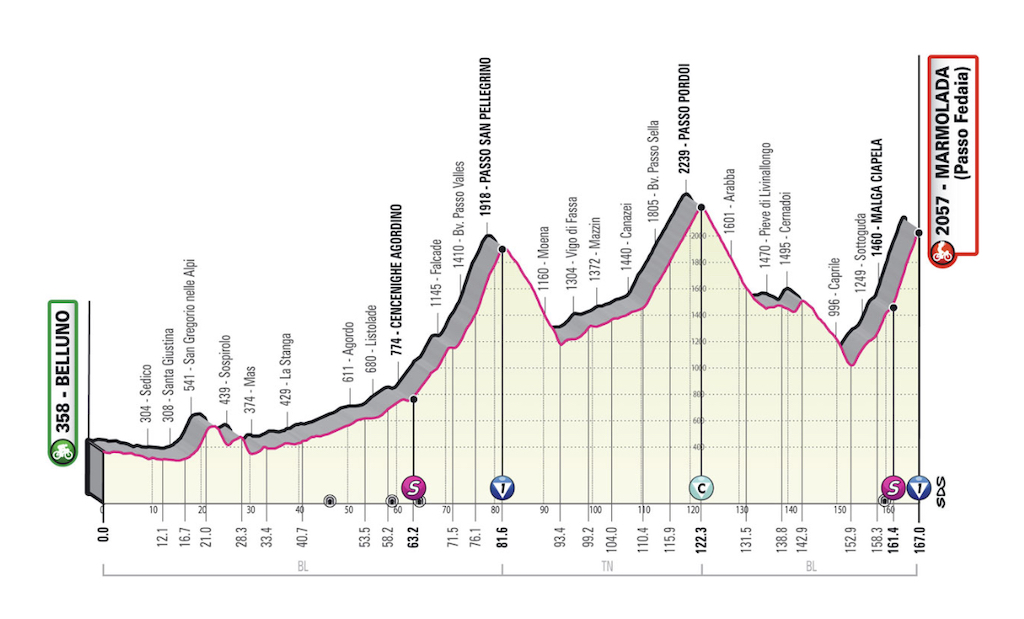

Crueler still, the climb comes at the end of arguably the most demanding day of the entire race. Stage 20 brings the Giro into the Dolomites and above 2,000 metres for the first time, with the Passo San Pellegrino followed by the towering Passo Pordoi and then the final haul up the Fedaia, a pass so often labelled with the name of the mountain above it, the Marmolada.

"It's already very hard because of the gradient, but then when it's a long straight like that, it increases the difficulty even more," Alessandro De Marchi (Israel-Premier Tech) told Cyclingnews. "The straightness of the road makes it seem infinite, and because you're going up slowly, it seems even longer. That's a really crucial point of the climb."

By statistics alone, the Fedaia is not the toughest ascent of this Giro, but its position, on the stage and in the entire race, means that it is likely to be the most decisive, not least because Richard Carapaz (Ineos Grenadiers) begins stage 20 with a lead of just three seconds over Jai Hindley (Bora-Hansgrohe).

Nothing bar time bonuses has separated them since the time trial in Budapest on stage 2, but three weeks of accumulated fatigue and ramps of 18% make for a heady mix. That dizzying cocktail, complete with a dash of high altitude, might just put a twist on a Giro d'Italia that has been heavy on suspense yet curiously light on excitement. The prospect of rain, too, only adds to the rigours of the day.

Altitude

In the mixed zone atop Santuario di Castelmonte on Friday, Carapaz allowed himself a smile when he was asked about stage 20. "The finale will be like being at home," Carapaz said.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The inference was clear. As an altitude native, Carapaz might reasonably expect to fare better at that rarefied height than Jai Hindley, who grew up rather closer to sea level in Perth. Then again, Hindley showed no inhibitions when he tackled the Stelvio en route to victory at Laghi di Cancano two years ago.

Then as now, Hindley has been inseparable from an Ineos foe in the final week of the Giro, though not for the want of trying. The Australian's Bora-Hansgrohe team looked to isolate Carapaz on stage 19 by setting a ferocious tempo on the climb of Kolvorat, but come the final haul to Santuario di Castelmonte, they were back in their usual posture, deftly jabbing and parrying without landing a critical blow.

Saturday's tappone offers the two leaders the last chance of delivering a knockout blow rather than face a points decision in the final time trial in Verona. Behind them, Mikel Landa (Bahrain Victorious), third at 1:05, is still not entirely out of the contest, while Vincenzo Nibali (Astana-Qazaqstan), fourth at 5:53 will look to sign off on his Giro career with a flourish.

The focus, however, is firmly on Hindley and Carapaz. Their deadlock has been total to this point, with even their teams seemingly unable to break one another entirely. Carapaz lost Richie Porte to illness early on Friday, just as Bora-Hansgrohe were forcing the pace on the front, but Ineos would later dictate the terms of engagement on the day's final climb. They will do it all over again in the Dolomites. Once more with feeling.

"Between Richard, Landa and Hindley, the strength left is more or less the same," Ineos directeur sportif Matteo Tosatto admitted. "But this is a very demanding stage, and the altitude might have an influence."

The route

When the weary survivors of this Giro flip through the Garibaldi to remind themselves of what awaits on the race's penultimate stage, they will be confronted by the three most intimidating words in all of cycling: classico tappone dolomitico. The author of the roadbook could probably have glossed over the details and left the synthesis of stage 20 at that. For those at the front of the race, at the back and in all the places in between, this is going to hurt.

The stage sets out from Belluno, hometown of Dino Buzzati, the novelist and journalist whose writing from the 1949 Giro captured the mystique of Fausto Coppi like few others. The opening 50km or so are relatively gentle, but from there, the race heads for the heights. First up is the Passo San Pellegrino (18.5km at 6.2%), familiar to Nibali as the site of so many altitude training camps during his time at Liquigas. The ascent features pitches of 15%, but its prime task here is to begin the winnowing process ahead of the day's key difficulties.

The second of the day's troika of climbs is the mighty Passo Pordoi, which brings the Giro above 2,000m for the first time. The road climbs for 11.8km at 6.8% and tops out at some 2,239m above sea level, making it the Cima Coppi, the highest point of this Giro. The Pordoi first featured in the Giro in 1940, when Gino Bartali was first to the top, and the lofty summit would remain beyond the reach of mere mortals for most of its early appearances in the race.

Coppi himself led over the Passo Pordoi five times during his career, including three times in a row from 1947 to 1949. Buzzati was in a car following behind Coppi on the third successive occasion, and he was struck by the discrepancy between the almost effortless progress of the apparition in bianco-celeste and straining of the flesh and bones labouring to keep him in sight. "Is he climbing? No, he's not climbing," Buzzati wrote. "He simply rides as though the road were as flat as a billiard table."

The Pordoi is the kind of place that inspires and intimidates in equal measure. With some 45km remaining and another brute of a climb to come, it seems unlikely to serve as a springboard for attacks from the podium contenders, but – much like Kolovrat on stage 19 – it will be the place where they set their teams to work in a bid to isolate one another. The descent to Caprile is long, but at this point in the Giro, the mental and physical toll is such that few dropped riders will be able to scramble their way back on.

The final climb up the Marmolada – shorthand for the 2057m-high Passo Fedaia – is 14km at 7.6%, but the toughest, double-digit section comes in that infinite stretch of road past Malga Ciapela. This stretch of road is hardwired into the collective memory of the Giro since its first appearance in 1975.

The most celebrated episode – inevitably – concerns the late Marco Pantani, who in 1998 reputedly didn't even realise he was climbing the Fedaia until he asked teammate Roberto Conti when the climb began. "We're already halfway up it," Conti reportedly responded. Shortly afterwards, Pantani was clear with Giuseppe Guerini, while Pavel Tonkov and Alex Zülle all but ground to a halt on the steepest portion. Another passage of mythology.

More tales will be written on Saturday, and not just at the front of the race. The Marmolada is the kind of climb where everybody reaches the summit with a story. De Marchi is among the few riders in this Giro to have raced up it in anger, but his recollection is affectionate.

"It was my first Giro, an epic day and I was really there enjoying the race," De Marchi said on Friday. "I think everybody was really scared about the climb and all the stage, but actually I have a beautiful memory of that. Coming back there is a nice feeling."

As ever, the Passo Fedaia will leave an impression on all who ride up it. And, who knows, it might even make an impression on the top of the general classification. Something has to give eventually.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.