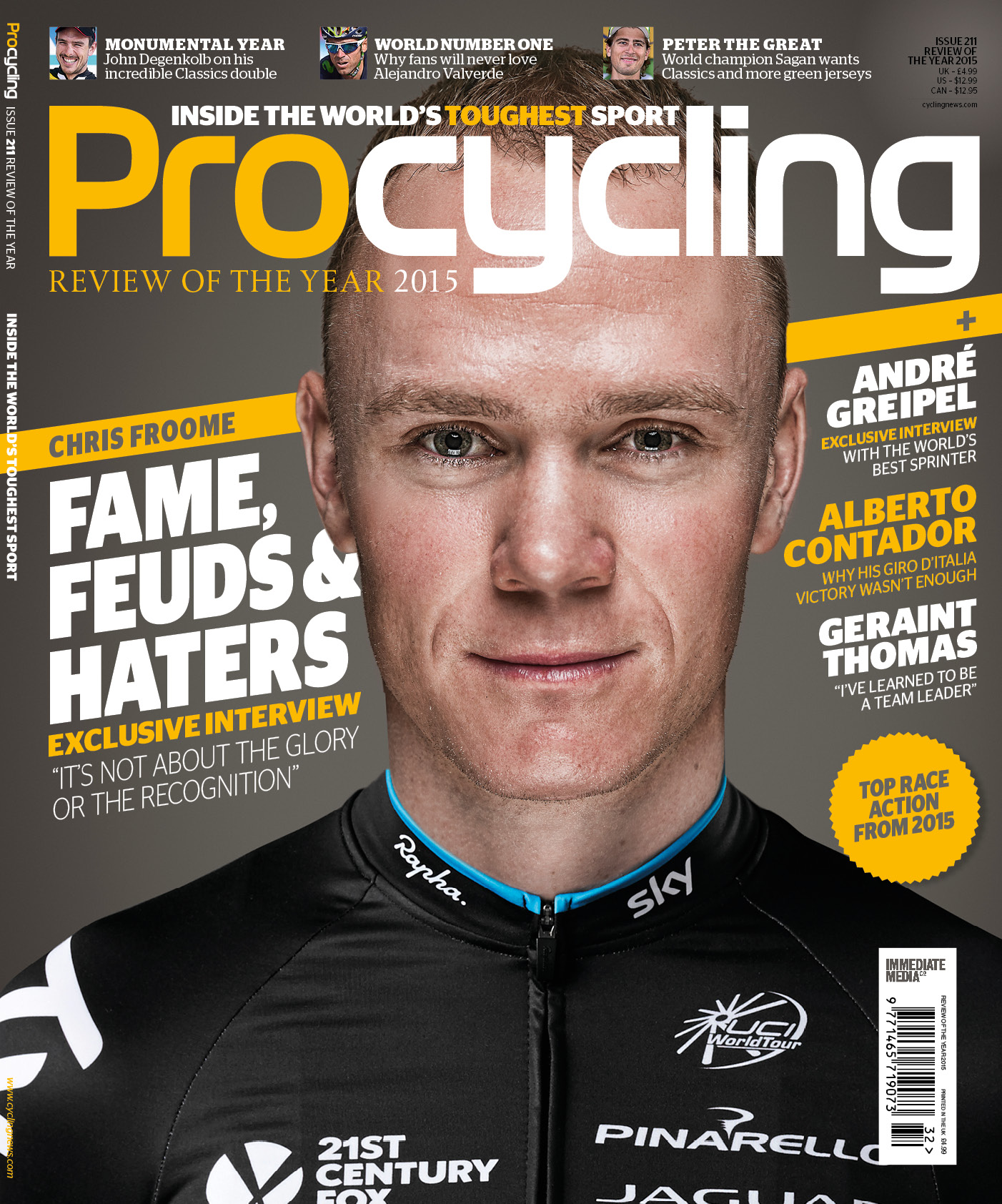

Chris Froome interview: Fame, feuds and haters

Procycling's exclusive interview with Team Sky's Tour de France winner

Step into a busy London street with Chris Froome in civvies, even with a photographer in tow, and chances are life will go on around the two-time Tour de France rider unperturbed. Not that he cares much. Fame and popularity are not high on his agenda. "That's not what I'm about," he'd told us earlier in the boutique hotel where he was staying. "It's not about the recognition or the glory." It sounds like a stock line from a world-class athlete but then there is nothing about his appearance to suggest the contrary: old-fashioned navy blazer over a green polo shirt, slim-fit black jeans and skateboarder's trainers.

It's the follow-up line, delivered with a passion that fans don't readily associate with Froome the two-time Tour winner, that is striking.

"What really drives me is the actual performance. I'm driven. I'm driven to try and win as many Tour titles as I can throughout my career; to have the biggest impact on youngsters wanting to have a good role model. Ninety per cent of everything I do, the training, the mental focus, it's geared towards trying to be the best athlete that I can be."

With those words still resonating, there's time to reflect on a successful year for Froome, even if it wasn't quite of the same vintage success as 2013. All the pre-Tour talk was that he was no longer the same rider. His abandonment through injury at the 2014 Tour, Alberto Contador's ability to contain him at the subsequent Vuelta, illness this spring and team insiders saying he simply wasn't as punchy as 2013 all contributed to a general marking down of the Kenya-born Briton.

Then he confounded the consensus in June. He added another Dauphiné success to his palmarès and, of course, a month later triumphed at a Tour that was notable for the abundance and quality of his rivals. Not since the early 1990s had such a glittering array of riders been in contention for the yellow jersey. Arguably, the deciding factor wasn't Froome but a team which squeezed the fight out of his opponents over three weeks. After a very strong opening week and a stinging attack on the first day in the mountains, Froome started cracking up towards the end as he battled illness and his rivals ratcheted up the pressure.

In victory, he enhanced his standing as the pre-eminent stage racer in cycling. Of the 27 stage races he started since the 2011 Vuelta, he's abandoned four and finished in the top five of 18 of the rest. Ten of those were victories. Nibali, the best figure for comparison, has started 31 stage races, finished in the top five 12 times and won six of those.

Froome needed all his resolve to remain focused at this year's Tour, which, in reality was a monument to his concentration and single-mindedness rather than his physical dominance. Aside from the tussle with his rivals, principally Nairo Quintana but also more personally with Vincenzo Nibali, he weathered a guerrilla assault on his reputation. French state-owned TV aired a damaging report on his performance in which the physiologist Pierre Sallet concluded that Froome's winning ride on La Pierre Saint Martin, the first mountain-top finish of the Tour, was 'highly suspicious'.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

"It seemed that this year at the Tour de France, 90 per cent of what the media wanted to talk about was the suspicion and the doubts around our performances. It felt as if that was the focus rather than the actual race, which was actually really exciting," Froome reflects, curiously toneless, doubtless sick to death of the topic.

Oddly, recounting the abuse the team faced on the road, Froome pulls his punches. "Certainly the stuff that was going on – my team-mates getting punched, having urine thrown at me, that was–" and he searches for the word "…ridiculous, bordering on disgusting behaviour.

"But at the same time it was almost as if that was just white noise on the side. If anything it really brought us as a team closer together. We wouldn't let this break us, ruin our experience of the Tour."

Two years on, Froome has so far failed to take the venom out of accusations of cheating. We say so far, because on Friday, Esquire magazine published the results of independent physiological testing he undertook after the Tour that's been combined with some historical data that stretches back before his transformation to his time with the UCI World Cycling Centre in 2007. He hopes it will help convince reasonable sceptics that he has an exceptional physiology and is not a doper. He seems to see little chance of persuading the hardcore fringe.

Why Froome bears the brunt of the aggression is a ponderable. His current rivals have never faced such questioning. Why not Nairo Quintana for taking 1:20 from Froome on Alpe d'Huez on the penultimate day of the Tour? Why not Vincenzo Nibali who rode almost the entire 2014 Tour in yellow with nary a doping question put his way, despite riding for Astana, a team with a murky history and Alexandre Vinokourov in charge? And why not Alberto Contador, who had already served a doping ban before exerting a vice-like grip on proceedings for most of the Giro?

To read the rest of the interview, buy the Procycling Review of the Year, which is available in shops from Friday December 4.

Sam started as a trainee reporter on daily newspapers in the UK before moving to South Africa where he contributed to national cycling magazine Ride for three years. After moving back to the UK he joined Procycling as a staff writer in November 2010.