Giro d'Italia 2014: Five key stages

Giro Countdown: four days to Belfast

Stage 8: Saturday, May 17: Foligno – Montecopiolo, 174 kilometres.

Rather like in 2012, the toughest mountain stages of this Giro d'Italia are shoehorned into the final week of racing. RCS Sport's aim, of course, is to maintain suspense in the race for overall victory until as late as possible, but such an approach can often be a double-edged sword. While Ryder Hesjedal duly provided the anticipated grandstand finish by divesting Joaquim Rodriguez of pink on the final day two years ago, the opening two weeks of that Giro were something of a damp squib, with controlled racing and a sizeable group of overall contenders decidedly reluctant to show their hands.

This time around at least, the terrain in the first half of the race seems more open to a dash of invention, and even if the early hilltop finishes at Viggiano and Montecassino seem unlikely to cause a major shake up of the general classification, the first real summit finish at Montecopiolo should prove more testing than the equivalent stage to Lago Laceno two years ago.

The day begins in the gently rolling hills of Italy's "green heart," Umbria, but the topography becomes decidedly wilder as the day draws on and the gruppo passes into the neighbouring region of the Marche. The Cippo di Carpegna (6km at an average gradient of 9.9%) rears into view with 60 kilometres remaining and heralds the beginning of real hostilities at this Giro. The race's first category 1 ascent was one of Marco Pantani's favourite training climbs, and this stage is the first of three dedicated to the memory of the late climber, who died a decade ago. The mercurial José Manuel Fuente put Eddy Merckx to the sword on the Carpegna in 1974, taking advantage of a section that kicks up to 14%, but it surely comes too far from the finish for the pink jersey contenders to go on the offensive here.

Instead, the two-part climb to the finish line provides a decent springboard for attackers. The category 2 Villaggio del Lago is followed by the briefest of descents before the category 1 haul to Montecopiolo. That makes for 18 kilometres of climbing in total and the average gradient of 6.3% is a deceptive one – the road to Montecopiolo ascends like a set of stairs, pitching up to 13% at some points before flattening out once again. Punchy climbers like Dan Martin (Garmin-Sharp) and Joaquím Rodríguez (Katusha) should enjoy this finish and, in particular, the 13% slope in the final kilometre.

Stage 12: Thursday, May 22: Barbaresco – Barolo, 46.4 kilometres. Individual time trial.

The mountain test to Monte Grappa in the final week is the more eye-catching of the Giro's two individual time trials, but this is the one more likely to have a significant impact on the fight for pink. Its positioning before the race's entry into the Alps lends a particular strategic importance to this time trial – even more than the Montecopiolo stage, this should provide the first real definition to a hitherto blurred general classification picture, setting the tone for the days to come in the Alps.

This 46km time trial is also less predictable and more likely to produce large time gaps than the Montegrappa test, for the simple reason that the majority of the pre-race favourites for the pink jersey are climbers who are far from comfortable in this discipline. There is one small mercy for Nairo Quintana (Movistar), Rodriguez et al, however – originally planned to take place on a largely flat parcours, the local organising committee managed to coax RCS into changing the route to a hillier one to showcase the hills of the Langhe, famous for their vineyards and truffles, and immortalised in the writing of Beppe Fenoglio and Cesare Pavese.

The alteration to the route has given the climbers a fighting chance of limiting their losses, and the course is uphill for the first 12 kilometres, gently climbing to the first time check at Boscasso before a swooping descent into Alba. The flat 15km section either side of the home of Ferrero Rocher is where the climbers will struggle, but the rouleurs will have their rhythm upset once again by the rolling finale through Barolo wine country.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

On paper, Cadel Evans (BMC) is the man most likely to make gains here, even if the Australian was strangely sub-par against the watch in last year's Giro – attributable, perhaps, to his truncated build-up to the race. In any case, if the veteran is to upset the odds at this Giro, he needs to gain a significant chunk of time on the likes of Quintana and Rodriguez here.

Stage 14: Saturday, May 24: Agliè – Oropa, 162 kilometres

An Alpine doubleheader on the penultimate weekend is something of a staple of the modern Giro, and this year's back-to-back summit finishes carry a particular poignancy, dedicated as they are to the late Marco Pantani. RCS Sport's decision to honour Pantani so explicitly has aroused a certain degree of unease, but there is no debate about the joy that he brought to fans in Italy and beyond. However, it would be a disservice to Pantani's memory to celebrate his exploits at Oropa and Montecampione without remembering – and regretting – the context in which they were produced. Pantani's tragic death becomes all the more senseless when no lessons are drawn from the events that led to it.

The long haul to the finish of stage 15 at Montecampione is probably the most difficult climb the Giro faces on this weekend, but the stage to Oropa is the tougher of the two days in the Alps and arguably more likely to provoke real fireworks among the overall contenders. Just over 100 miles in length, the bumpy opening half of the stage winds its way northwards before the Alps loom into view in the final 80 kilometres.

The Alpe Noveis, 8.9km with a testing middle section that averages over 11%, is the first of three mountain passes on the menu and signals the beginning of the softening up process. Next up is the climb to Bielmonte, which is not as tough, but is still a long, grind to the summit. The long descent from there could discourage attacks from distance from the general classification contenders but even so, there should be plenty of tired legs in the pink jersey group once they hit the foot of the climb to Oropa.

After a relatively benign start, the 11.75km climb kicks up to its steepest section at the midpoint, when the gradient stiffens to 13%. From there, it's a tough grind to the chapel at the summit, a UNESCO world heritage site, and it seems precisely the kind of climb on which Nairo Quintana would expect to shine. Pantani won here in 1999 after slipping his chain at the base of the climb and then went into overdrive to make up the ground and pass no fewer than 49 riders en route to stage victory. At the time, it seemed a victory for the ages. In hindsight, it stands as a landmark of an era of excess.

Stage 16: Tuesday, May 27: Ponte di Legno – Val Martelllo/Martelltal, 139 kilometres

Take two. This exact stage was included on last year's percorso, only for heavy snowfall in the Dolomites to force the cancellation of the stage on what proved to be a grim day all around for the organisers. Rather than reporting on an epic battle over the Gavia and Stelvio, the Giro's press pack instead spent the day relaying the tale of Danilo Di Luca's positive test for EPO, news of which broke shortly after RCS had confirmed that the stage would not go ahead.

Last year's snowbound Giro – two further mountain stages were truncated due to the conditions – led to much wringing of hands over whether a race had any business climbing mountains in excess of 2,000 metres so early in the year, and expect the polemica machine to spin into overdrive if the Gavia (2618 metres) and the Stelvio (2758 metres) again prove impassable.

Let's hope that lightning (or snow) doesn't strike twice because, on paper at least, this stage promises be the most explosive of the entire race, a delight for the tifosi and a nightmare for all but the purest of climber in the Giro peloton. Three mighty mountain passes are squeezed into just 139 kilometres of racing on a stage that seems to follow the template laid down by the Tour de France's miniature epic to Alpe d'Huez in 2011, when the attacking began almost as soon as the flag dropped and scarcely let up thereafter.

After rolling out of Ponte di Legno, the peloton faces directly into the imposing Passo Gavia and anybody who fails to hit the ground running after the rest day is going to be on the back foot here and struggling to make the time limit come the finish. Quite simply, Gavia is a brute – 16.5km long with an average gradient of 8%, slopes of up to 16% and yawning upwards to 2618 metres above sea level.

The fearsome Stelvio follows immediately after the plunging descent to Bormio. At 2758 metres above sea level is Cima Coppi, the highest point in the race, and while its average gradient of 6.9% is not the steepest, its sheer length (21.7km) and altitude means that the front group will be a very select one indeed come the summit.

The final haul to Val Martello has never been climbed before in the Giro and it drags on for a seemingly infinite 22 kilometres, which can be broken into three distinct parts. The first point of respite comes in the form of a short descent after 6km of climbing, before the road kicks up again for long grind of 11km or so. The road briefly flattens out with 3 kilometres remaining, before a final, agonising kick up to the line. Those already struggling after the Gavia, Stelvio and lower slopes of Val Martello could be brought almost to standstill on the 14% wall 2km from the summit.

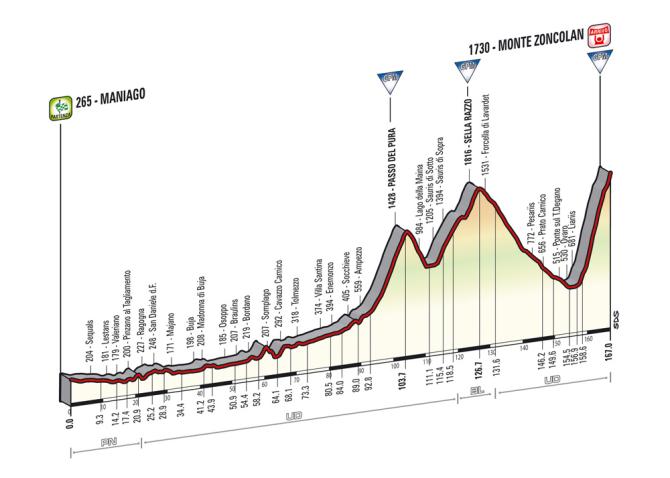

Stage 20: Saturday, May 31. Maniago – Monte Zoncolan, 167 kilometres

The current penchant for super steep climbs truly took hold around the turn of the century, when the Giro and Vuelta a España began to outdo one another in search of ever more vertiginous slopes, both seeking to distinguish themselves as being tougher than La Grande Boucle. So it was that the Zoncolan was introduced to the Giro in 2003, in partial response to the Vuelta's Angliru, and the climb has quickly built up a reputation as one of the most feared in Europe.

The Zoncolan is preceded by the Passo del Pura and the Sella Razzo, but it's hard to imagine that anyone with designs on pink will move a muscle before the final climb. Once again, the Zoncolan is tackled from its toughest side, the 10.1km western approach from Ovaro, which has an average gradient of 11.9% and a brace of stretches in excess of 20%. Indeed, between the third and seventh kilometre of climbing, the gradient doesn't drop under 14% and the "flatter" final two kilometres still average some 8.5%.

On paper, then, this is the toughest climb in the race, but curiously, the time gaps on the Zoncolan are often smaller than expected – even the strongest riders can only go so fast on a gradient of 22%, and so this extreme terrain often suits those limiting their losses rather than those going on the offensive. Only in 2010, when Ivan Basso pulled away from Cadel Evans in the finale, has the Zoncolan felt like the most decisive moment in the Giro, but this is the first time it has featured so late in the race, and RCS will be hoping for a dramatic finale akin to that provided by the Angliru on the penultimate stage of last year's Vuelta, when Chris Horner denied Vincenzo Nibali overall victory.

If gap between the maglia rosa and second place is measured in second rather than minutes ahead of the stage, then the Zoncolan could provide a thrilling denouement to the Giro. In any case, the final stretch of the climb from Liariis is something of a natural amphitheatre and there should be a cauldron of noise to greet the survivors as they grind their way to the summit, ahead of the following day's finale in Trieste.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.