Why are more juniors making the leap directly into the WorldTour? A deep dive into the new normal

From training to travel, Cyclingnews looks at how junior riders are tackling the changes that come with signing a professional WorldTour contract

With the likes of Remco Evenepoel and Zoe Bäckstedt, and now Matthew Brennan and Cat Ferguson, the WorldTour is seeing younger and younger riders stepping up to the senior ranks and having instant successes.

But in a sport that is notorious for high volumes of training and equally high demands when it comes to travel for races and training, how do these riders deal with the sudden jump from junior racing and training loads up to the top flight of the sport?

To find out, I spoke with several fledgling top-tier riders who are already lighting up the peloton and their team coaches.

Why is high training volume so important?

To put things into a little more context, let’s first look at why professional road riders do such large volumes of training. The races that they compete in, even the shorter one-day events, are more often than not around 150-200 km long for men and 110-160km for women. This makes them highly aerobic-intense races, meaning that they use systems that require optimisation of oxygen transfer, usage, and breakdown of substrates for fuel.

Aerobic performance consists of a huge myriad of factors, but key among them is the aerobic respiration system. This process begins the moment we inhale air. As we consume it, we absorb some of the oxygen, but not all of it. That is known as diffusion, and is generally a genetic factor. Where things start to become trainable is in the next step of the process.

Once we have this oxygen in the blood, we then need to transport it around the body. This is our cardiovascular system, and to improve this, we need to be able to increase cardiac output, as well as blood plasma volume, to allow for more blood to be transported and more oxygen to be carried. Haemoglobin and haematocrit can be improved via altitude training, or more nefariously via blood doping, but the other elements are trainable.

We also need a greater network of capillaries, smaller blood vessels, to carry this oxygen-rich blood to the muscles. Once there, perfusion occurs, as the oxygen is carried from the blood into the muscle tissue. In the muscles, we meet the mitochondria. These cells use oxygen to break down substrates, fat and carbohydrates, and produce ATP - the energy that drives every single function in our body. More capillaries, more oxygen delivered, more mitochondria, better functioning mitochondria, and better substrate availability all contribute to greater aerobic performance.

So why is high training volume so important for this? Well, it’s because long-duration training results in several key performance adaptations in the body, which help these processes. This is why WorldTour riders spend a lot of time at low intensity, because you can’t do 30 hours a week at higher intensities than your first lactate threshold (Zone 2) without accumulating significantly more fatigue.

During long-duration cycling, there are several key elements which help to improve aerobic performance.

At the heart of these adaptations is a molecular powerhouse known as PGC-1α (peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1-alpha). This transcriptional coactivator is considered the master regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis, the process by which new mitochondria are created within muscle cells.

During long-duration low-intensity rides, subtle but chronic metabolic stresses, such as slight Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) depletion, calcium flux, and mild reactive oxygen species accumulation, activate upstream signals like Adenosine Monophosphate-Activated Protein Kinase (AMPK) and p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (p38 MAPK). These, in turn, stimulate PGC-1α expression, triggering a broad genetic program that builds more mitochondria and enhances the oxidative capacity of existing ones.

This increase in mitochondrial density and function has profound effects on endurance.

It enables muscles to generate more energy through aerobic metabolism, which is far more efficient and sustainable than anaerobic glycolysis. As a result, athletes can produce the same power output with lower lactate accumulation and greater reliance on fat as a fuel source, sparing precious glycogen stores and delaying fatigue. In essence, you’re teaching your muscles to become ultra-efficient engines.

The story doesn’t end at the mitochondria, though.

Long rides also stimulate the growth of new capillaries in muscle tissue through upregulation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), a signal protein essential for angiogenesis. As skeletal muscle undergoes the repeated strain and mild hypoxia of endurance exercise, VEGF expression is elevated, particularly through the same PGC-1α pathway. The result is a denser capillary network, allowing for more effective delivery of oxygen and nutrients, and more efficient removal of waste products like carbon dioxide and lactate.

Another key adaptation involves the optimisation of substrate metabolism. Over time, long-duration cycling enhances the muscles' ability to oxidise fat, not only because of greater mitochondrial content but also due to the upregulation of fat transport and oxidation enzymes like CPT1 (carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1). This metabolic shift, favouring fat over carbohydrate, enables endurance athletes to go longer at moderate intensities without dipping into limited glycogen reserves. It’s a shift that can be directly observed in physiological testing as a rightward movement in the “crossover point” where fat and carbohydrate usage intersect.

Central cardiovascular adaptations also play a role.

Repeated long rides increase the size and compliance of the left ventricle, allowing more blood to be pumped per beat, a higher stroke volume. This means a greater cardiac output at a lower heart rate, further supporting sustained efforts over time. These changes contribute to a reduced heart rate at submaximal workloads, improved thermoregulation, and overall better aerobic efficiency.

Perhaps one of the most undervalued effects of long-duration training is its impact on lactate kinetics. Not only is less lactate produced thanks to better mitochondrial efficiency, but lactate clearance improves as well. The expression of monocarboxylate transporters (MCT1 and MCT4), which shuttle lactate in and out of muscle cells, increases with consistent endurance training. This dual effect of lower lactate production and enhanced clearance pushes the lactate threshold higher, allowing athletes to sustain higher outputs for longer without tipping into anaerobic metabolism.

In summary, long-duration, low-intensity cycling is the molecular sculptor behind some of the most critical adaptations in endurance performance: more mitochondria, better blood flow, increased fat oxidation, and enhanced lactate management. Hence, its prevalence in WorldTour training.

So now we know why the WorldTour riders do so much training, but how do 18-year-olds step up to that huge increase in volume?

The answer depends on who you ask.

Scope for improvement

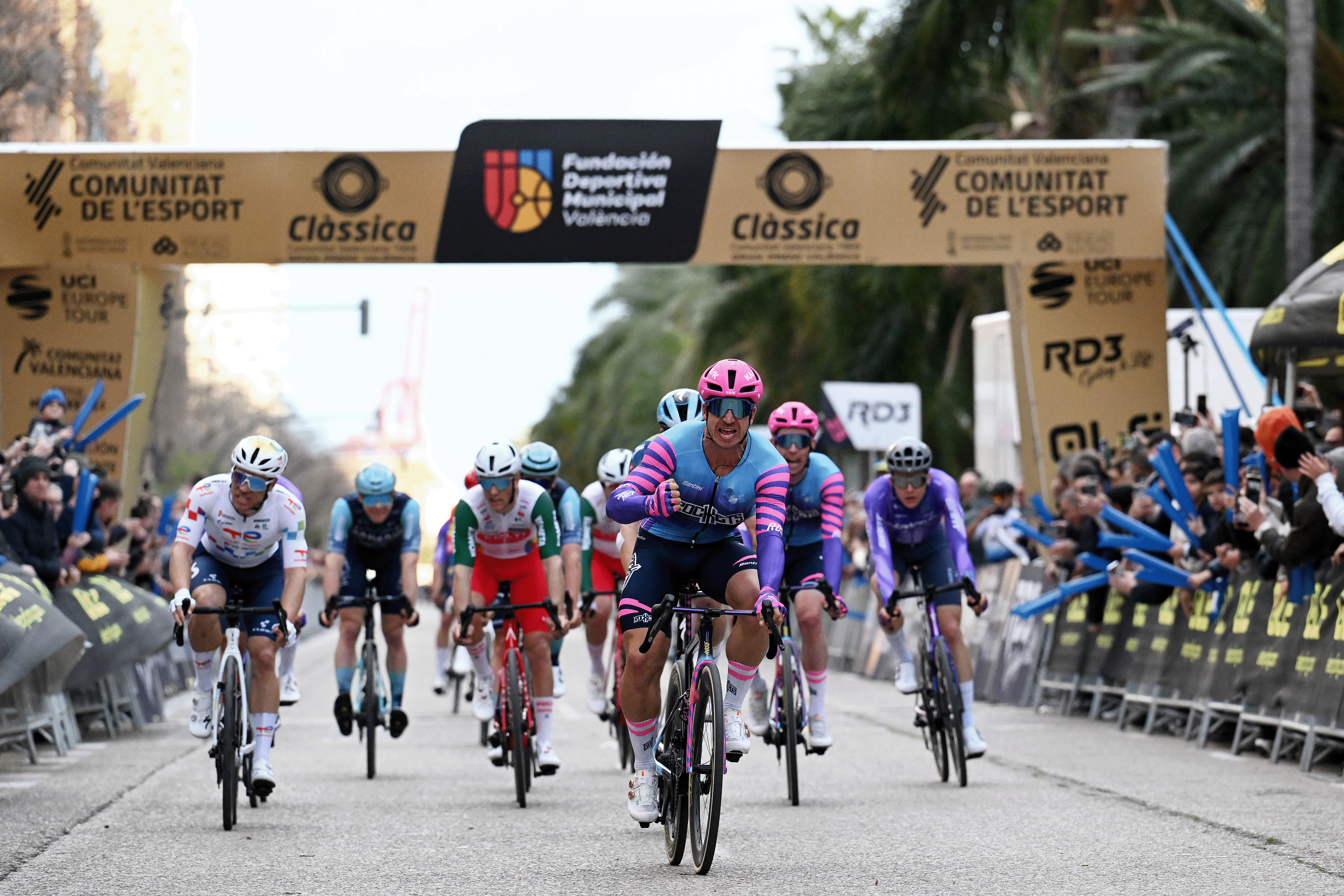

One of the star performers in the men’s WorldTour this year has been Matthew Brennan, becoming the most successful teenager in men’s cycling, overhauling Remco Evenepoel’s win tally at the same age.

I had a chat with both Brennan and his coach, Robbert De Groot, at Visma-Lease a Bike to find out more about the training that he does, but also how the team judges this and progresses it.

Interestingly, for Brennan, his training volume as a rider in the WorldTour is not as large as many might assume. He says that generally, his training consists of "20 hours more often than not, some weeks more, some weeks less."

The biggest changes for him have been how the training is structured.

"Coming from not having a coach as a junior, to having one at Visma's U23 team, it was completely new for me. Very different working on intensity and structure, which helped massively in U23. I went through U23 and up to WT with the same coach, so he knows me well. He knows when I’m getting tired and knows what I need for development. [The] right amount of rest at the right time."

When I asked him how the team approach the training, having specific targets in mind or just focusing on a proper rate of adaptation, Brennan said: "I’m being developed as a rider, not as a bike racer. The team is working to make me the strongest version of myself, and then seeing what happens when we build. I’m not building for specific races."

To shine a bit more light on why the team put the rider's development front and centre rather than performance targets, I spoke with Brennan's coach, De Groot, as well. I also asked him what exactly the team looks for when recruiting junior riders into their U23 development team, the pathway to the WorldTour squad.

"It’s very individual, as some riders have more hours under the belt than others, so they can move to [the] WorldTour faster. 10-15 hours is what we look for in junior riders," he said.

"It is very important that we monitor the loading of the riders well and the reaction to loading for the riders. You train the rider carefully, knowing their past and what they’ve done, and you slowly build and monitor how they progress with more volume and intensity. The top riders are a benchmark to see how the younger riders develop.

"It is sometimes trial and error, but you always avoid going over the edge, hence the importance of gradual increase to give their training more ‘body.’ Most young riders react quite well to increasing training load, especially as school work finishes. If they are in school, this is accounted for with tailored programmes to allow for better training without excessive stress or doing large volumes on weekday evenings."

Given the 10-15 hours a week, I asked De Groot why the team doesn’t want to see junior riders already able to do larger training weeks upwards of 20 hours.

"Junior riders are doing 10-15 hours, but how they adapt depends. Some riders do more hours, say 25 hours a week, but then that can limit where they can go. If a rider comes in with 10, we up to 15, if 15, we up to 18 as we build up over years and years, gradually. Now, it’s not just the volume; it's the type of training as we build and load the riders over the years. During certain training periods, this will vary as well. Some weeks are 14, some 20, some big weeks are 25, but the intensity will vary as well as more hours of training means reduced intensity unless it’s a race.

"We tend to see that riders who do more when far younger hit the roof earlier, as there is nowhere else to go. You can’t continually progress from 20 hours as a 16-year-old. Some nations do more, Norwegian schools, for example, give more time for activity, so culture impacts the development rate as well."

This certainly raises an interesting point in rider development, as often, the information available to junior riders on how best to train focuses around what the WorldTour does, rather than seeing this as something to build up to gradually, some junior riders can be lured into the idea of being able to do that training volume too early in their progression, and thus limiting potential scope for improvement.

This is similar to how training has been approached for Cat Ferguson or Team Movistar, who has already won at WorldTour level in her first season racing up from junior.

"For me, as a very much over-trainer already as a junior, there was a change in training going to the WorldTour; however, maybe not as big of a difference as anticipated. If I had it my way, I would do more training than I do now. However, the team is putting great emphasis that I take it easy and slow [over] the first couple of years; therefore, the training increase isn’t too noticeable for me to be honest.

"Of course, there are some changes. I would say the main one being that I am doing at least one or two rides around five hours now, which as a junior I did but not as often as once a week. So yes, I would say there has been a small increase in volume in one to two training sessions per week, but the rest of my week I would say is pretty similar to last year’s training with a similar ratio of intensity."

A lot more racing

Another huge change that junior riders experience when they move up to senior levels is the racing. Firstly, the duration of the races changes quite dramatically. As we mentioned before, junior boys' races go from around 100-120km maximum, up to 160-200km on average, which is why fuelling becomes such a big factor.

For the junior girls, it is also a large swing. Most junior girls' races are around 2-2.5 hours in total length, with WorldTour races being 3-4 hours for stages of stage races, and 4+ hours for bigger one-day races. This means that although the time increase of races is similar to that of the boys, the relative percentage increase is closer to double.

Speaking again with Ferguson, she was able to share some great details about how cycling has changed for her, moving from junior to WorldTour.

"The biggest change for me has definitely been fuelling during training and races. As a junior, I had knowledge on what I needed to do, and did sometimes do it. However, with races only being two hours, sometimes if I did forget to take a gel in the first hour and therefore didn’t hit the planned 60-70g/hour, I didn’t find it impacted the race results, whereas now it’s detrimental. When I did some races last year as an apprentice for the team, my main problem was finding opportunities and remembering to fuel, and when I did, I then really struggled to digest the carbs. So I put a big focus over the winter of making sure I hit the carbohydrate target for each training session with my nutritionist. We really did start from the beginning, almost. In November, I was fuelling my training with 25g per hour, and by January, I was doing 75g."

In the UK, the junior girls do have a slight advantage over the boys, in that they can race National A-level events. For reference, the East Cleveland Classic in 2024, which Cat won, was a three-hour race, far closer to what can be expected in the WorldTour. Whereas junior boys can’t race National A events in the UK, which can be 160-180km long, similar to some stages of WorldTour races.

It could potentially be a contributor to why junior girls from the UK have been more likely to step up straight to the WorldTour than the boys have. But then, a lot more men’s WorldTour teams have U23 Continental-level development teams associated with them than women’s WorldTour teams, a sign of the still-existent disparity in funding between the two.

The other huge change for riders is the amount of travel and associated race days. From January until June this year, Brennan has amassed 29 race days in six countries, while Ferguson, from March to June, has done 19 across five countries.

Speaking with Ferguson, the combination of more races internationally and stage races, which require transfers from stage to stage, results in a significant increase in the race travel compared to when she was racing for the Shibden Apex junior team and the British Cycling junior road team.

"Now, it seems I do almost as much travel as training sometimes! Definitely compared to last year, it’s a considerable amount more, mainly due to just the increased amount of race days I do now."

This is another important area that riders need to adapt to. As a coach of many junior riders racing internationally, I've noticed that, just as training loads gradually increase over the years, so does the exposure to extensive travel.

At times, riders can spend nearly three to four weeks mostly away from home, driving from race to race, with perhaps a couple of days between back home. In training, it’s generally regarded that a travel day is not a rest day. Spending long hours cooped up in a car, or standing around in airport queues, is not conducive to rest, and it adds an additional stress load to the stress-rest equation that coaching is all about balancing.

Ferguson also brought up another very interesting aspect of racing for a WorldTour team, which is that for her, there was a big change in how the sport is approached.

"The biggest change for me going from junior to the WorldTour is not the training, race difficulty, or fuelling, it’s the almost change of sport itself.

"What was a very independent sport, with every race being about myself and my own goals, has changed into a team sport. It’s a challenge I have really enjoyed and will continue to enjoy, learning about how best to optimise and work within a team while still being an individual.

"What I really mean by this is more learning to deal with the pressure of being within the team. I definitely feel more pressure when I know that if I don’t do my job properly, it doesn’t affect me, but it affects my teammate. That feeling of not wanting to let someone else down when under great physical and mental stress is very unique and it applies to every situation when in cycling, whether that’s when I have to lead someone out into a climb, follow attacks, or even if I am the team’s leader for that race.

The pressure is much greater, as if I don’t achieve that result, it isn’t just a loss for the work that I have put in, but also all my teammates, staff and DSs. This, combined with the extremely high physical and tactical level of all the girls in the WorldTour, makes it a very big challenge."

Why are younger riders performing better quicker?

One of the reasons that junior riders are now being signed up to the WorldTour earlier and earlier is that the relative performance of these riders has increased exponentially over the last five years or so.

One of the key components to this is greater access to smarter training and power meters. There is still great importance to riding for fun and learning skills rather than just looking at numbers. However, with access to smart training platforms and training plans in apps like TrainerRoad and Zwift, as well as a higher prevalence of coaching for junior riders, there has been a relative increase in performance among younger riders.

For reference, while out on a training camp with the junior development team I work with, Tofauti EveryoneActive Mojaco, a feeder team for Team PostNL Picnic, one of the first year juniors comfortably set a time up the Col De Rates of 14 minutes flat during a five hour ride going up there at more than 6w/kg. He was signed to a WorldTour team by the end of his first year as a junior.

There has also been a big increase in the wider understanding of proper nutrition. Riders are going off more than just water and bananas in their training rides, and as a result, can train better, recover better, and adapt better.

However, as previously mentioned, WorldTour teams want to see riders who actually still have scope for improvement. This is a big part of why most WorldTour teams now not only have under-23 teams, but some have junior teams, and all of them have talent scouts.

These staff members will look at all the junior racing that is going on, and if a rider shows promise and potential, the team will reach out, connect that rider’s TrainingPeaks to theirs so they can analyse their training data, and often invite the rider out for training camps or testing weeks with the team to assess them physiologically. I’ve been present on these testing days, and as well as raw power output and race craft, the teams look at a myriad of factors.

How do the riders manage with being self-supported and cooking the right meals? Do they keep their bike and accommodation clean? What is their mindset as a rider, an athlete, and also a potential employee of the team? It’s an area of professionalism that junior riders need to be able to show in addition to their performance on the bike, as they are sometimes going from living at home and going to school, to being employed full-time by a team and living by themselves in another country. It’s a huge step up.

Finally, junior riders are now being accepted into the WorldTour more readily with a change in the mindsets of riders and teams.

Previously, a neo-professional needed to have completed their time in the under-23 ranks on a development team before being deemed ‘ready’ for the WorldTour. They then joined the team with the expectation of working for more senior riders who had ‘earned their place’ in the peloton. Any upstarts would quickly be put in their place, as riders were seen as peaking at 27 for racing, with the exception of sprinters, so young guns had to learn the trade and earn respect. Nowadays, these young riders are already proving themselves worthy of leading teams, putting out power figures that are daunting to even seasoned and successful established professionals. Teams are sometimes signing them with the expectation that they will lead and achieve results immediately.

Another reason for these riders being signed younger and younger by teams is also the race to secure talent. It used to be that two-year contracts were the norm, with three years showing great investment by the team in a rider. Now, five years and beyond is not uncommon, and WorldTour teams are signing up junior riders before they are even in the junior ranks.

Leon Atkins was signed by Lidl-Trek while he was still a youth rider. It is a great amount of faith by a team put into a rider, and where they might be in four years. On the one hand, you don’t know how a rider will develop in terms of growth and progression as a youth rider; no one does. On the other hand, if they show enough raw physical potential, then providing them access to WorldTour support from a young age is likely going to help nurture and develop them into an even stronger rider than without that support.

Looking at Isaac del Toro and Tadej Pogačar, who both have long-term contracts with one super team, you can see why other teams are trying to lock down the next potential dominant rider, especially while their stock is likely to be lower. If they snap up the next Pogačar, then that team potentially claims the biggest races, which in turn attracts the biggest sponsor investments.

Stars that shine the brightest, fade the fastest?

There is, however, a potential risk to all of this super-fast rider development, especially with ever-growing race seasons and calendars, and for some teams, a race to accumulate WorldTour points. That problem is the potential chance of burnout.

We have seen this before, Cormac Nisbet in 2024, along with fellow Quickstep rider Gabriel Berg, both decided to stop pursuing their racing careers in part due to the pressures of the sport, but also the limitations in activities outside of that they could pursue.

Being a professional cyclist may sound like living the dream, and for some, it really is. However, these athletes do not just ride their bikes for money. Every single minute of every day is purposeful, with each minute of sleep being essential, every gram of food consumed fulfilling a purpose, and weeks of the year spent travelling from one race hotel to the next. It is a 24/7 kind of job with just an ever-shrinking off-season providing a moment of respite from what can be a relentless job.

There are, of course, many riders who enjoy the process and these aspects of life, but then for these juniors being signed with promise and potential being weighted onto their shoulders, there can be a great deal of pressure, and not necessarily the support networks to help them deal with this.

Mental health in sport has come a long way over the last decade or so, but it is still an area that can be very difficult for a lot of athletes. As mentioned, transitioning from a child living at home and attending school to moving away, often to another country, and spending much of the year travelling while adapting to complete self-dependence is a significant challenge. It’s similar to university, of course, but arguably more demanding and often there is a far smaller pool of people in the same position as these riders to empathise with.

Ferguson was able to share some insight into how her team, Movistar, approached this, and also the support she has had since the junior ranks from British Cycling.

"There is a psychologist in the team (Movistar), who I have never spoken to, but I think if I mentioned I wanted to, or was struggling with anything, then I would be referred to them definitely. However, it isn’t something that has been suggested as an idea.

"Within British Cycling, there is a lot of support around this, and I have had multiple calls with many people surrounding this change in programme. Within Movistar, as they see me so often, and it really has a family feel, they definitely would be immediately aware if I were the slightest bit struggling or off. Everyone is always pushing themselves to the limit, so if you’re mentally struggling, it very quickly becomes knowledge.

"I think that this family feeling within the team is almost the same support as speaking to any professional for me, as I really feel comfortable with my teammates and they have taken me in as almost a younger sister that I can always tell anything and be myself with."

Changes in mentality and attitudes

With a combination of access to higher levels of coaching from a younger age, changes in mentality and attitudes within the sport at the highest level, and greater prevalence of talent scouting looking for the next world beaters, it is becoming more common to see juniors and teenage riders stepping up to the WorldTour and instantly having an impact.

But the sport is brutal, relentless, and requires a level of commitment and professionalism that can be hard for youngsters to adapt to so quickly.

Increased travel days, moving to a new country, and going from homework deadlines to having a role to play within a progressional organisation.

It’s sink or swim, and even the best support teams can’t always help a rider float.

However, it is good to see, across multiple teams, that there is a strong emphasis on consistent rider development and focussed progression, giving these riders room to grow, and in doing so, seeing the emergence of some seriously exciting talents.

Freelance cycling journalist Andy Turner is a fully qualified sports scientist, cycling coach at ATP Performance, and aerodynamics consultant at Venturi Dynamics. He also spent 3 years racing as a UCI Continental professional and held a British Cycling Elite Race Licence for 7 years. He now enjoys writing fitness and tech related articles, and putting cycling products through their paces for reviews. Predominantly road focussed, he is slowly venturing into the world of gravel too, as many ‘retired’ UCI riders do.

When it comes to cycling equipment, he looks for functionality, a little bit of bling, and ideally aero gains. Style and tradition are secondary, performance is key.

He has raced the Tour of Britain and Volta a Portugal, but nowadays spends his time on the other side of races in the convoy as a DS, coaching riders to race wins themselves, and limiting his riding to Strava hunting, big adventures, and café rides.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.