Why does the Tour de France keep getting faster? Sonny Colbrelli and Bahrain Victorious find out

Four bikes from across the eras go head-to-head with some curious results

It seems every year of late we are being treated to the "Fastest Tour de France ever", or the fastest stage, or a combination of both. Understandably, given that in the past the riders were so full of drugs they were more pharmacy than human, it may be hard for some to reconcile the fact that riders now are ostensibly clean, but significantly faster.

Now, teams dedicate vast resources to optimising every minute aspect of performance, known as 'marginal gains'. The bikes, clothing, and equipment have been aerodynamically optimised, bespoke nutrition plans are made for every rider, and appropriate rest is given, along with significant time spent at altitude or in hypoxic hotel rooms. Tyres, larger now, have lower rolling resistance, drivetrains are waxed to save every last Watt, and in-race nutrition has been honed to a fine art. When teams bring mattresses on the road to ensure their riders sleep properly during a big race it's no great surprise to see average speeds edging ever upwards.

Yes, the riders also have better coaching, better strength and conditioning, and better diets too, but there’s no denying that the hyper fixation on wattage at an industrial scale has left us with bikes nowadays that are markedly more speedy than what you’d see in the Colnago archives from decades past.

How much faster, though? Well, Bahrain Victorious took Paris-Roubaix winner, and sadly recent retiree thanks to a heart condition, Sonny Colbrelli out onto the road armed with four bikes from different decades to see how much faster the best road bikes have become. On test were a thoroughly modern 2023 Merida Scultura, a 2013 Pinarello Dogma 65.1, a 2003 Cannondale Six13, and a Carrera Podium from 1989, all pitted against one another multiple times in controlled conditions both on the flat and uphill.

The bikes and the tests

Starting at the top we’ve got a 2023 Merida Scultura, as currently raced by Bahrain Victorious and one that we’ve also had time to test. A full Dura-Ace setup, with Vision finishing kit and modern, form-fitting kit from Alé and a modern Rudy Project helmet.

Back to 2013, we have a Dogma 65.1 from Pinarello, back when they were sponsoring Movistar, running a Campagnolo Super Record groupset with rim brakes, and deep Bora Ultra Two wheels and FSA finishing kit; note the round bars. Slightly scuppering the continuity, the kit is a more modern Adidas arrangement from the very early days of Team Sky, but we’ll gloss over that.

From the early 2000’s we’ve got a Cannondale Six13, a meld of carbon tubes and aluminium tube junction areas formerly ridden by Damiano Cunego during his time at Saeco. Mavic Ksyrium wheels and a Campagnolo Record groupset round out the build, save for Cannondale Hollowgram cranks. Kit of the era was from Kappa.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Lastly, the Lugged Carerra Podium Team Edition from the late ‘80s, running Dura-Ace like the most modern bike in the test but this time with downtube shifters. The most notable part of the kit has to be the helmet cover; perhaps an accidental aero wattage gain?

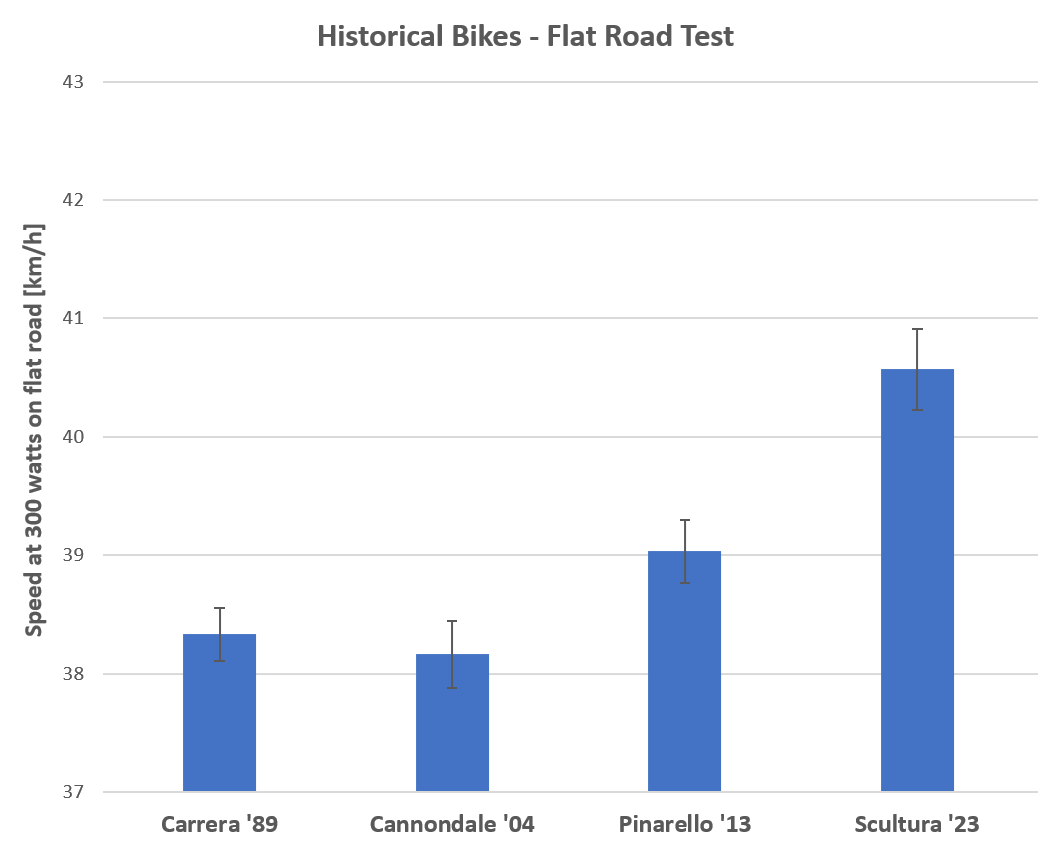

Testing was completed on two sections, one flat and one hill. The flat test was ridden at a set wattage on as flat a road as could be found, measured by a set of power pedals so that could be standardised across each bike.

The segment was ridden out and back at least three times to take into account any wind interference and to provide more data. It was timed as a rolling start rather than a standing start, with 300m or so to get up to speed before the virtual timing gates. Speed was measured using a Garmin bike computer, effectively in the same way as it would measure a Strava segment, rather than using real timing gates. As well as a timed section, speed and power data were amalgamated to produce a coefficient of drag (CdA) for each setup.

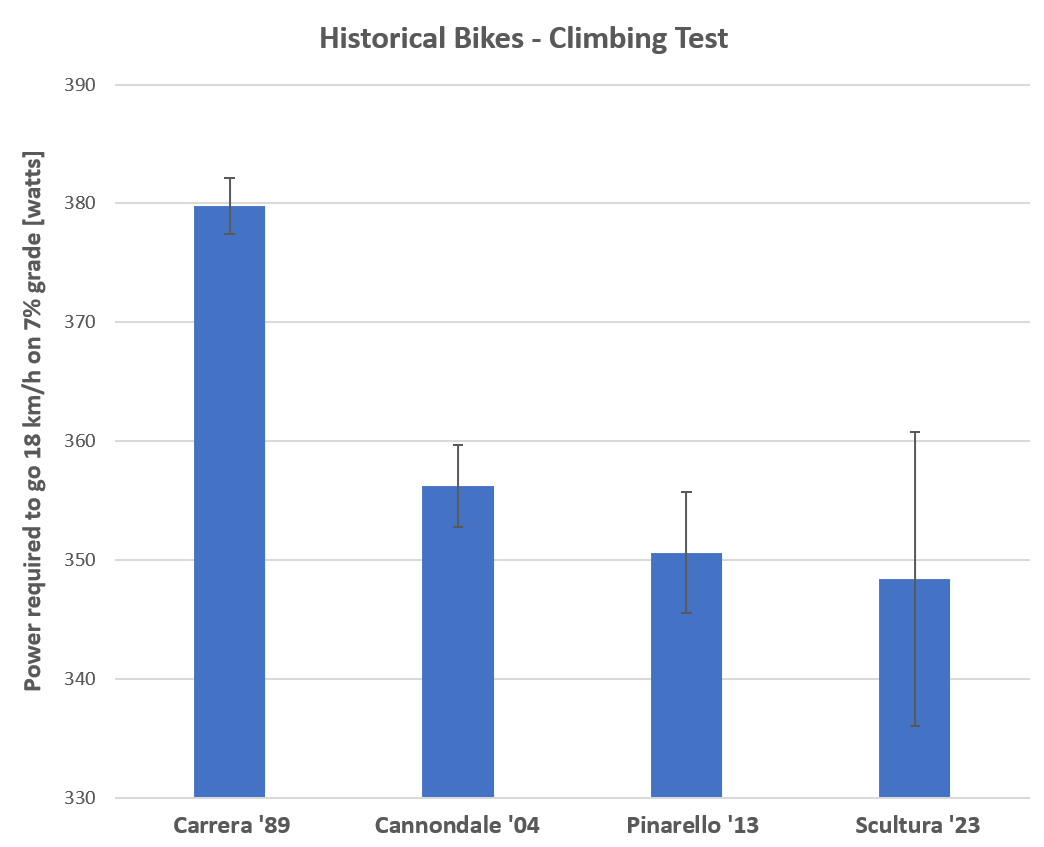

A second test was then conducted on a hill of around 6-7% for around 1km under the same conditions to see if the same differences on the flat also rang true uphill.

The results

Episode 21 of season seven of The Simpsons, titled “22 short films about Springfield”, featured a moment when Chief Wiggum gets his tie caught in a hot dog roller at a gas station. “Oh boy”, he utters as he is pulled inexorably towards his demise, “This is going to get worse before it gets better!”. The same seems to ring true for these bikes.

Taking things in the round it’s no great shock that the Merida Scultura of today is faster in every way than a 1989 Carrera with downtube shifters. What is interesting is that the Cannondale from 2004 required a greater power output to go 40kmh on the flat, and was slower at 300 watts on the flat than the oldest bike on test.

Given the advancements in aerodynamics, and the focus on it especially in recent years, it’s also no great surprise to see the modern Merida, with its fully integrated setup (and also perhaps a bike that Colbrelli has optimised his position on) is leagues faster on the flat that the Pinarello of 2013, requiring over 30 watts less to tick along at 40kmh, and at 300 watts it was a full 1.5kmh faster. Over the least efficient bike and kit combo on the flat, the Merida was over 50 watts more efficient at 40kmh.

However, things are a different story uphill, with the starkest difference in performance between the Carrera and the Cannondale. Around 25 Watts more to go 18kmh on an 8% gradient, or just shy of 1.5kmh slower at 360 Watts. It seems that, before aero had become a big influence, the differences that a lower weight could make uphill were stark.

When bikes were already light, butting against the UCI weight limit, the differences aero makes uphill was more marginal. Between the Pinarello and the Merida for example there’s only a fraction of a kilometre per hour gain, within the error range, for the same test.

With the graphs above, you can interrogate the data further, and it does go without saying that this is a small sample size, but it does pose some interesting questions.

We’re seeing wattage gains diminishing as the years go by, so is the next frontier going to be more introspective; optimising the body rather than the rider. Perfect nutrition, optimised rest? We see it with altitude camps and hotels with hypoxic rooms to allow riders to perform better in the high mountains. Given what’s on the line it’s going to be interesting to see where the next advancements will be made, and how much gain they actually offer for the effort involved.

Will joined the Cyclingnews team as a reviews writer in 2022, having previously written for Cyclist, BikeRadar and Advntr. He’s tried his hand at most cycling disciplines, from the standard mix of road, gravel, and mountain bike, to the more unusual like bike polo and tracklocross. He’s made his own bike frames, covered tech news from the biggest races on the planet, and published countless premium galleries thanks to his excellent photographic eye. Also, given he doesn’t ever ride indoors he’s become a real expert on foul-weather riding gear. His collection of bikes is a real smorgasbord, with everything from vintage-style steel tourers through to superlight flat bar hill climb machines.