Giro d'Italia 2020: Five key stages

The days that could decide the Corsa Rosa

The first Giro d’Italia 2020 presentation in Milan was held in October 2019. Since then, major disruptions across the globe due to the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic brought revisions to the date and courses for the 103rd edition of the Corsa Rosa.

Traditionally the first Grand Tour of the season, the Giro is now pressed between the Tour de France and Vuelta a España, and mixed in are a few of the Classics, trading the early summer May dates for cooler autumn colors and temperatures October 3-25.

The 2020 Giro was originally slated to start in Budapest as well, but race director Mauro Vegni later confirmed that Hungary would not host the Grande Partenza of the rescheduled race. The first four days will now be held in Sicily, meaning the Giro will be an all-Italian race, with only a brief visit to France during stage 20 to climb the Col d'Izoard. The final weekend features a tough mountain stage to Sestriere before the race concludes on October 25 with a 16.5km time trial in Milan.

There are three individual time trial stages, including a 15.1km race against the clock to start the three-week event from the hill-top village of Monreale on stage 1.

The stage profiles highlight the 40,000 metres of climbing across 50 classified climbs and five summit finishes. The October date could bring the risk that the highest mountain passes might fall foul of the weather but the autumnal colours will be unique for the Italian Grand Tour.

Here is a look at some of the stages that leap off the page as being pivotal to the final destination of this year's maglia rosa.

Stage 3: Enna-Etna (Piano Provenzana), 150km (October 5)

Same same but different. For the third time in four years, the Giro climbs Mount Etna in the opening week but race organiser RCS Sport have at least tried to ward of the nagging sense of déjà vu by bringing the race up the volcano by yet another new route.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In 2017, the Giro finished at Rifugio Sapienza after climbing the exposed route from Nicolosi, while twelve months later, the race followed a different, more sheltered approach via Ragalna. A brisk headwind in 2017 meant that the GC contenders were reluctant to attack one another behind stage winner Jan Polanc, but the fare was more combative in 2018, when Simon Yates bridged across to his teammate Esteban Chaves near the top.

This time out, the Giro will scale Mount Etna from Linguaglossa, climbing to a new finish location at Piano Provenzana, 1,775m above sea level. The final climb is 18.2km in length and though the average gradient of 6.8 per cent isn’t the most daunting, the final 3km pack a considerable punch. The gradient rarely drops below 9 per cent in the finale, and the ramps of 11 per cent with a kilometre or so to go lend themselves as an obvious springboard for late attackers in the manner of Yates in 2018.

Etna will loom on the horizon from the moment the race leaves the start in Enna, and while the finishing climb is the stage’s only mountain pass, the road rises and dips all day long as the gruppo skirts around the base of the volcano and through familiar spots such as Nicolosi and Zafferana Etnea.

Ordinarily, a mountaintop finish this early in a Grand Tour doesn’t provoke big differences due to the relative freshness of the peloton, but this Sicilian chapter is subtly different to the Giro’s recent trips to the island.

It’s also worth noting that, on paper at least, the haul up Etna is the toughest ascent of the Giro’s opening stanza. In 2017, the race’s second weekend featured the Blockhaus, while the Giro tackled Montevergine and the Gran Sasso d’Italia at the same point a year later.

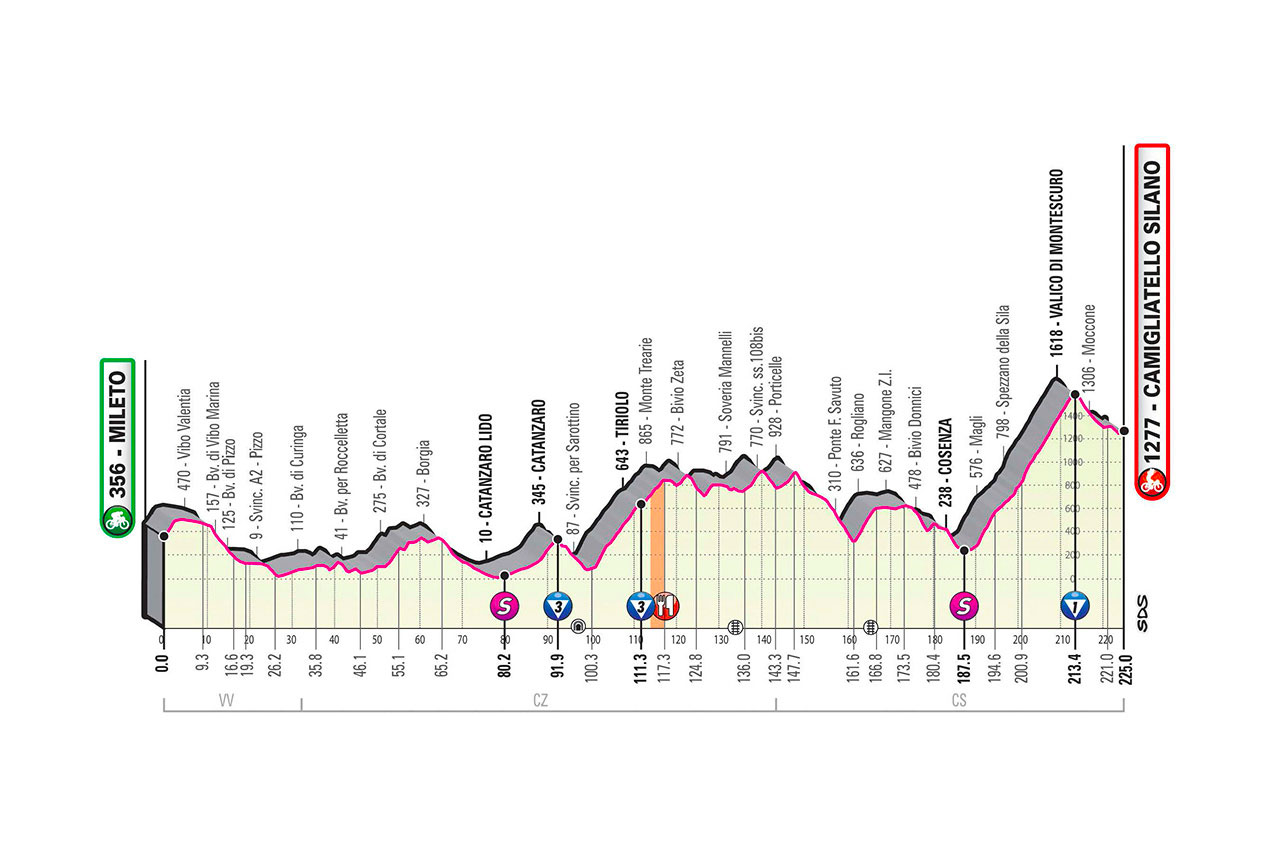

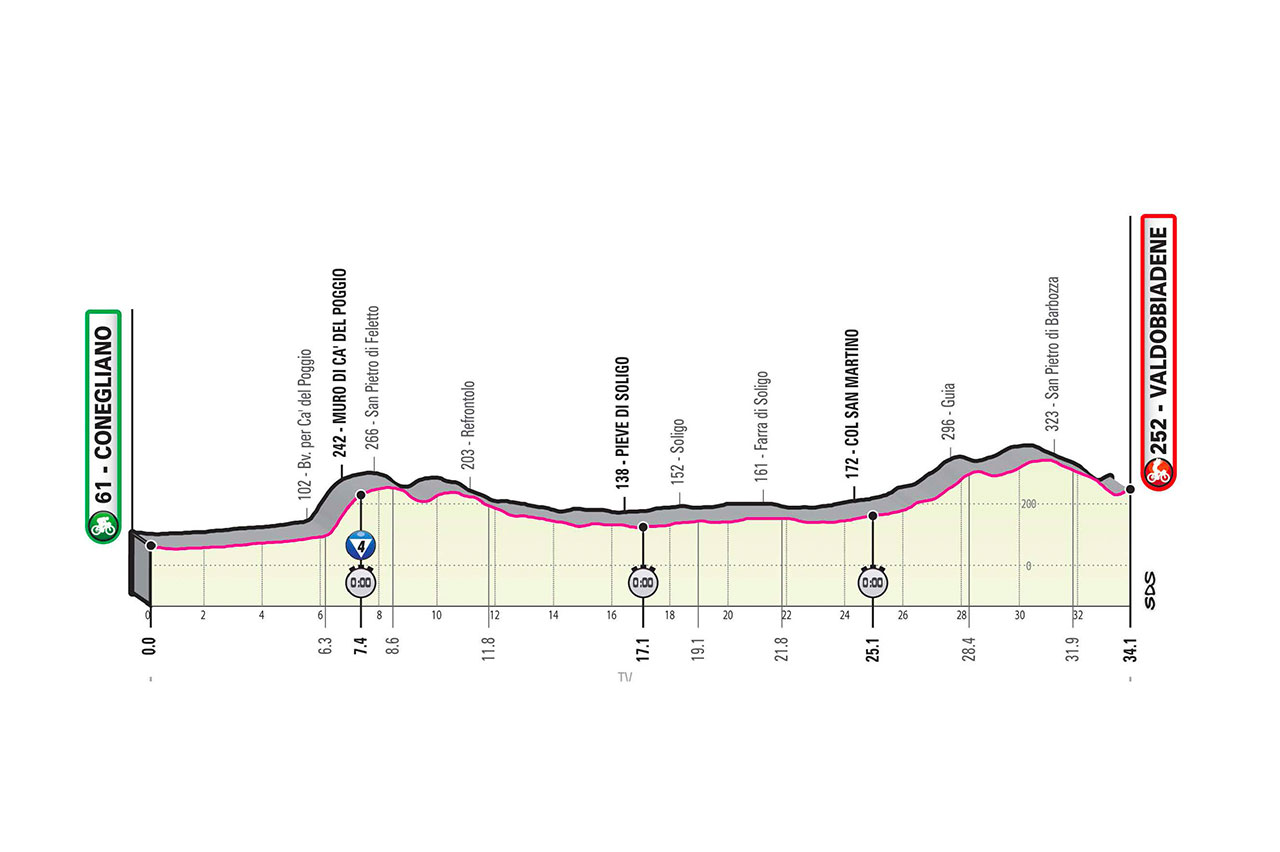

Stage 14: Conegliano-Valdobbiadene, 34.1km individual time trial (October 17)

This 33.7km test in Prosecco country calls like a siren to men like Tom Dumoulin and Primož Roglič of Jumbo-Visma, who built their Grand Tour wins around stages precisely like this, namely a time trial through rolling terrain that lends itself to opening big gaps.

Dumoulin set the tone for his 2017 Giro by dominating the Montefalco time trial, while Roglič produced something similar in Pau on the recent Vuelta a España. It’s also worth noting that – his later travails on the Finestre notwithstanding – Alberto Contador effectively won the 2015 Giro thanks to the gains he made on Fabio Aru in a strikingly similar Valdobbiadene time trial, which also took place on the race’s third weekend.

On that occasion the stage was almost twice as long. Indeed, at a distance of 59.4km, it was the longest time trial in any Grand Tour in the past decade.

The discipline has been afforded rather less space in three-week races ever since, though this undulating test to Valdobbiadene, together with the short opener in Sicily gives the rouleurs a chance to amass a buffer on the pure climbers ahead of an arduous final week at high altitude. It remains to be seen, however, how much the time triallists can (re)gain in the concluding 16.5km leg to Milan.

The Valdobbiadene time trial demands several changes in rhythm, starting with the early climb of Muro di Ca’ del Poggio, centre-piece of the 2010 Italian Championships, which is classified as fourth category climb. The first time check at the summit should be a reliable indicator; those who fail to settle early could find themselves incurring big losses come the finish.

As in 2015, the finale brings riders along rolling hills through Guia and San Pietro di Barbozza, before a final kick to the line Valdobbiadene.

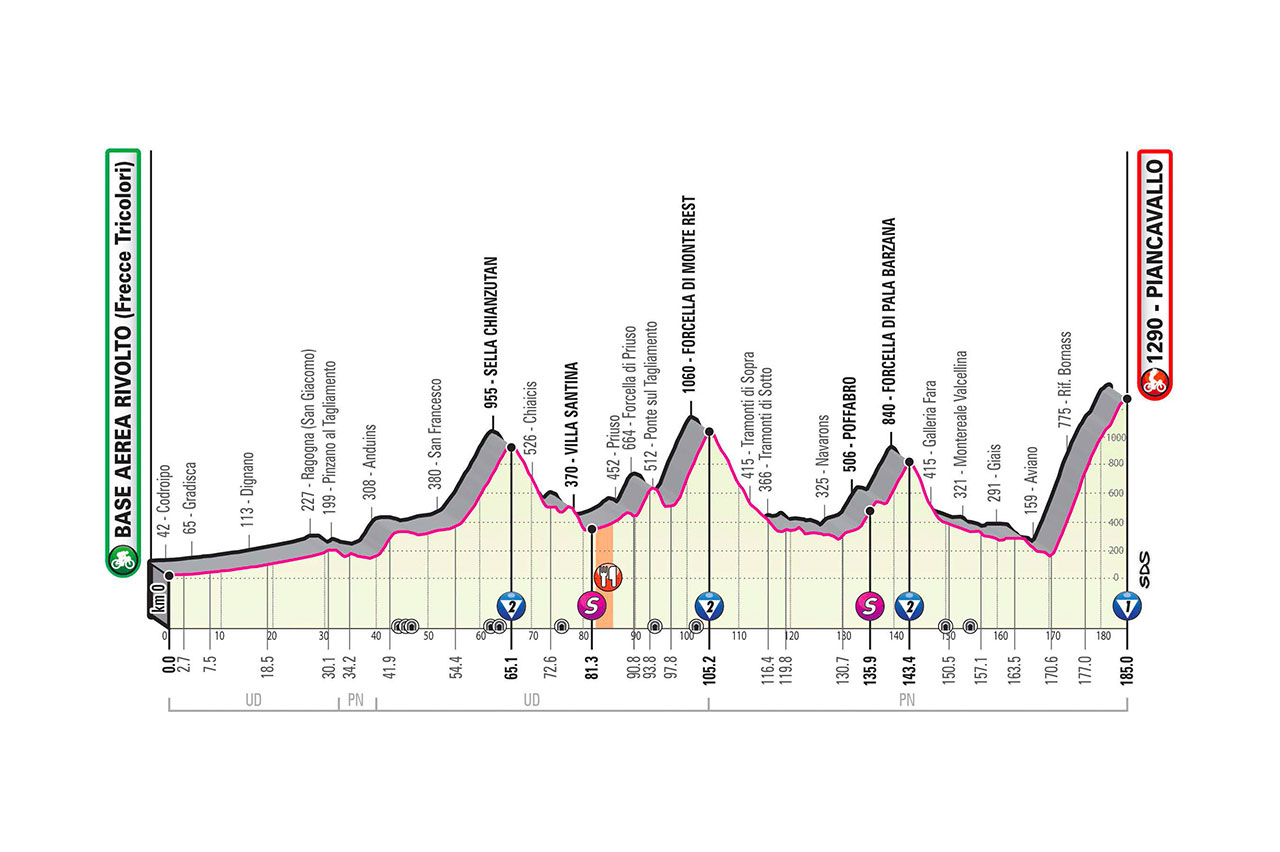

Stage 15: Base Area Rivolto-Piancavallo, 185km (October 18)

Stage 17 to Madonna di Campiglio is undeniably more demanding on paper, with some 5100m of total climbing including Monte Bondone, but this leg through the Carnic Alps might yet prove to be of greater strategic importance, especially if the high-altitude final week ends up being curtailed due to inclement weather.

On a stage sandwiched between the Valdobbiadene time trial and the second rest day, the men with designs on overall victory must make the abrupt transition from pushing large gears to climbing in the little ring, and it will be a surprise if some lofty GC challenges don’t lose momentum here.

At first glance, the stage profile isn’t especially daunting. Only two of the day’s four classified climbs exceed 1,000 metres in altitude, but in this corner of Italy, the uneven gradients and twisting roads can provoke some breathless racing.

In 2018, Simon Yates claimed the pick of his hat-trick of Giro stage wins at the end of a gripping leg to nearby Sappada, while this stage also features terrain covered on the tumultuous day in 1987 when Stephen Roche divested his Carrera teammate Roberto Visentini of the maglia rosa.

The day’s first ascent is the 955-metre-high Sella Chianzutan, which is followed by the Forcella di Monte Rest, scene of Roche’s attack on Visentini all those years ago.

This time around, the Giro tackles the pass from the opposite side, climbing the sinuous road from Ponte sul Tagliamento and dropping to Tramonti di Sotto. The Forcella di Pala Barzana is next on the agenda before the final haul to Piancavallo, which is included on the Giro route for third time.

Mikel Landa won at the summit in 2017, while Marco Pantani triumphed in 1998. The ascent has been designated as the race’s ‘Cima Pantani’ as RCS Sport continues its policy of celebrating the myth of the climber while blithely ignoring the part professional cycling and its culture played in his tragic and senselessly premature death.

The road from Aviano to the 1,290-metre-high summit of Piancavallo is 14.5km in length at an average gradient of 7.8 per cent. While there are tougher climbs to come in the final week, this ascent was demanding enough to see Dumoulin temporarily concede the pink jersey to Nairo Quintana in 2017.

The steepest section comes after 4 kilometres, when the gradient reaches 14 per cent and stays in double digits for more than 2,000 metres.

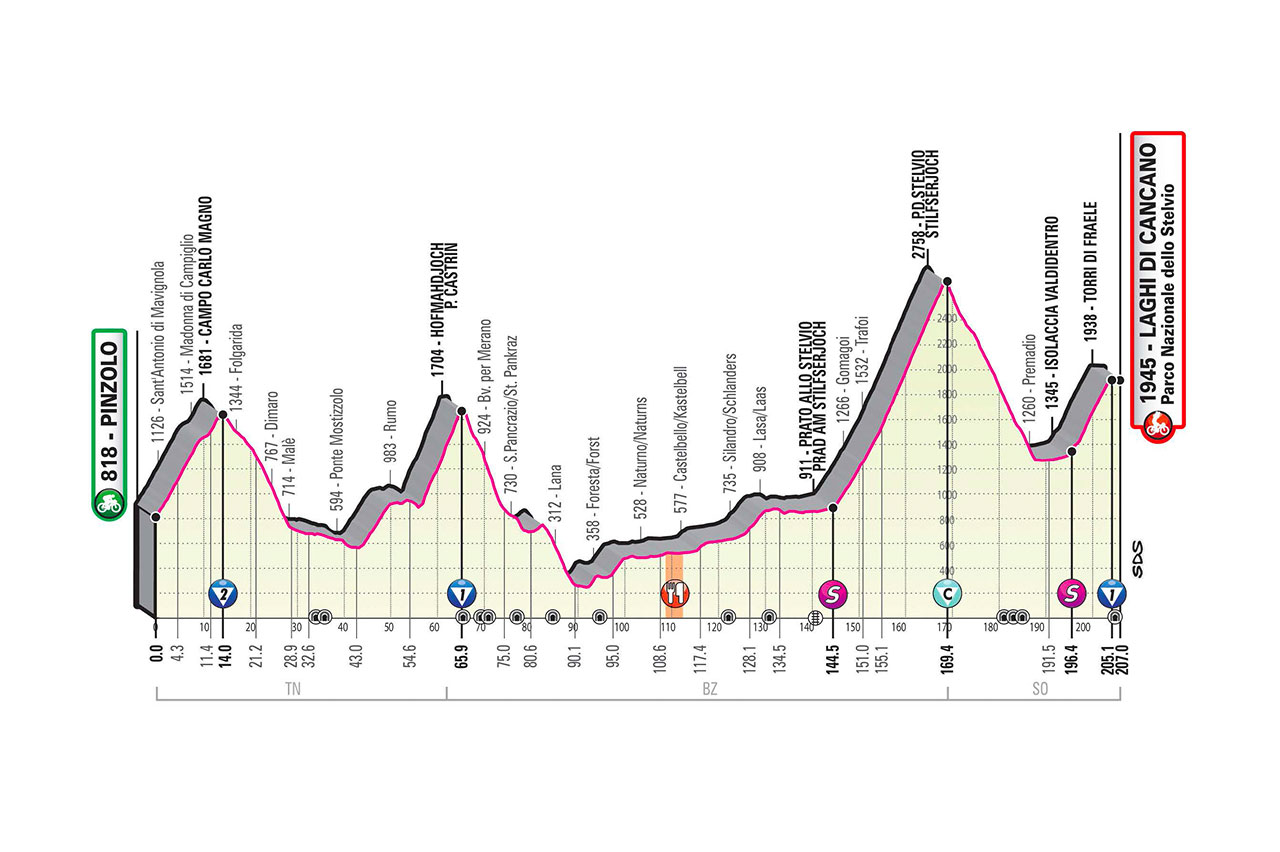

Stage 18: Pinzolo-Laghi di Cancano, 207km (October 22)

As in 2019, the Giro shoehorns the bulk of its mountainous stages into the third week of the race, though in May last year the race’s finale arguably proved less arduous in practice than it had initially appeared on paper, and not only because the Gavia was removed from the route.

The proof will be in the racing, of course, but three stages of more than 5,000m of climbing apiece add up to a most testing finale in 2020.

After the previous day’s summit finish at Madonna di Campiglio, the Giro heads for its highest point on stage 18, with the Passo dello Stelvio – all 2,758m of it – serving as the Cima Coppi for the 10th time.

It should be noted, however, that the Stelvio was also due to be the Cima Coppi in both 1988 and 2013 but had to be removed from the route due to heavy snow, a constant hazard in May and early June at that altitude.

Assuming it goes ahead as planned, the stage looks set to be a brute. The climbing starts from the moment the flag drops in Pinzolo, as the race immediately tackles the Campo Carlo Magno (14.3km at 6 per cent), followed shortly afterwards by the lengthy Passo Castrin. The 23.7km haul from Rumo has an average gradient of just 4.7 per cent, though those figures mask its true difficulty as the slopes pitch up towards 10 per cent in the final 8km and scarcely relent all the way to the top.

The centre-piece, of course, is the mighty Stelvio, which is tackled from its most celebrated side, the hairpin-garlanded grind from Prato allo Stelvio. It makes for a seemingly interminable ascent of 24.7km at an average gradient of 7.5 per cent, and it gets harder as it goes on, with long stretches in excess of 9 per cent nearer the summit.

A 20km descent follows before the final ascent of Laghi di Cancano, which features on the Giro for the first time having been the site of a stage finish at the Giro Rosa last summer.

The 10km haul to the finish is on a narrow, twisting road that cuts through the rocks via a series of tunnels and turns to gravel in the final kilometres, making it far more than a mere epilogue to the Stelvio.

All told, the day features 5,400m of altitude gain.

Stage 20: Alba-Sestriere, 198km (October 24)

The Giro’s Alpine coda is broken up by a flat and long stage to Asti before the gruppo enters the fray one last time with this tappone that snakes its way across the Franco-Italian border and back.

The start is in Alba, amid the gentle hills of the Langhe, but the road is climbing from the outset and the terrain grows increasingly rugged on the approach to the day’s first classified climb, the soaring Colle dell’Agnello, whose 2,744m summit marks the French frontier.

The Agnello is 21.3km long at an average of 6.8 per cent, but it grows steeper as the air gets thinner, and riders will face pitches of 15 per cent on the final approach to the top.

Although the Agnello only made its Giro debut in 1994 and has appeared sparingly in the intervening period since, it has the feel of a classic ascent, not least because of the drama that unfolded on the corsa rosa’s last visit in 2016. When Vincenzo Nibali went on the offensive over the top of the climb, maglia rosa Steven Kruijswijk was initially able to follow only to crash on the descent as he strained to follow the Sicilian’s line. Nibali soloed to stage victory at Risoul and sealed overall victory the next day at Sant’ Anna di Vinadio, while Kruijswijk had to settle for fourth place.

The Col d’Izoard follows immediately afterwards at 14.2km in length and 7.1 per cent average gradient. The pass and the haunting Casse Desert have appeared in the Giro on seven previous occasions, most notably in 1949, when Fausto Coppi was first to the top during his famous solo raid between Cuneo and Pinerolo. It returns after a 13-year absence from the corsa rosa – Danilo Di Luca led at the summit in 2007 – though more recently, it was a stage finish on the 2017 Tour de France.

On the Giro’s last three visits to the Izoard, in 1996, 2000 and 2007, the stage has finished over the other side in Briançon. This time, there are still 32 kilometres and two more mountain passes to go for the gruppo. The last section of the stage follows the exact same route as the Briançon-Sestriere time trial that decided the 2000 Giro in favour of Stefano Garzelli.

The Col de Montgenèvre (8.4km at 6 per cent) brings the race back into Italy, before a short and fast descent leads to the base of the final haul towards Sestriere, the ski resort developed by the Agnelli family to service nearby Turin.

The final climb is not the steepest, but its demands (11.4km at 5.9 per cent) will inevitably be accentuated at the end of a stage – and Giro – like this one.

The ascent has witnessed some late drama on the Giro, after all. In 2005, Paolo Savoldelli salvaged his maglia rosa here after scrambling down the Finestre, while a decade later, Mikel Landa crossed the line in tears after being ordered to desist from attacking to help his Astana leader Fabio Aru.

In 2018, meanwhile, Chris Froome led over Sestriere during the startling 86km solo attack that won him the Giro.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.