- 2, 2.5, and 3-layer

- Breathability rates (MVTR)

- Cam-locked zip

- DWR

- Double zip

- ePE

- ePTFE

- ePU

- Face fabric

- Gore-Tex

- Gore-Tex fabrics

- Gore-Tex Infinium

- Helmet compatible

- Hydrostatic head

- Membrane

- Packability

- Pertex and other fabrics

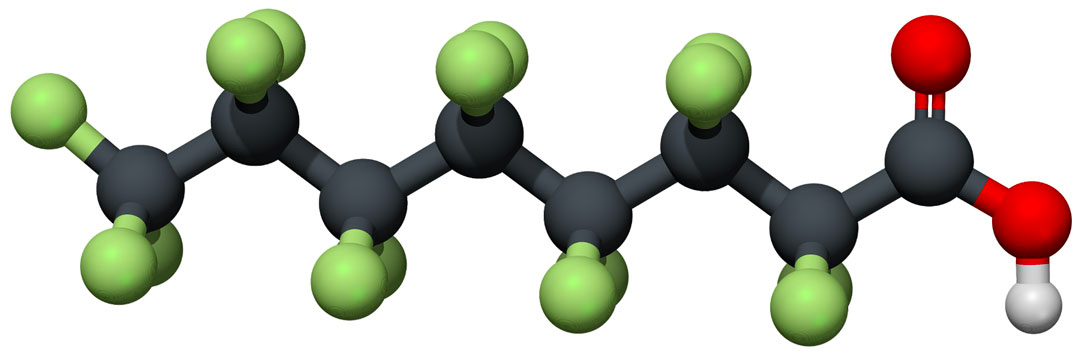

- PFAS

- Pfas-free

- Pit-zips

- Reflective detailing

- Shakedry

- Taped seams

- Welded seams

- Wetting out

Sit me and one of my riding buddies within earshot of a non-cyclist in a local cafe and I’d wager our chat would slip completely under the radar. Not because it’s dull - although perhaps not everyone wants to hear about the best waterproof cycling jackets - but because it would be laced with enough jargon to totally baffle any casual listener.

The world of cycling is absolutely stuffed with specialist terminology. That’s all well and good for a tech journalist like me, or my equally nerdy mates, but it can make the sport feel a bit impenetrable - especially when you’re shopping around for tech-heavy kit. Weather you’re looking for the best winter cycling jacket, a new groupset, or maybe the best winter cycling gloves, you’re going to be greeted with a whole host of jargon.

Take waterproofing, for example. What on earth is “PFAS”? And how can a single waterproof jacket somehow boast a three-layer membrane? With so many fabric brands, coatings, and design features competing for attention, it can be tricky to make sense of it all. So, to help stop you drowning in the jargon, I've put together this waterproofing terminology buster, in alphabetical order. Come back to it whenever you need, and as brands add more jargon to the pot I'll update it.

2-, 2/5-, and 3-layer waterproof fabrics

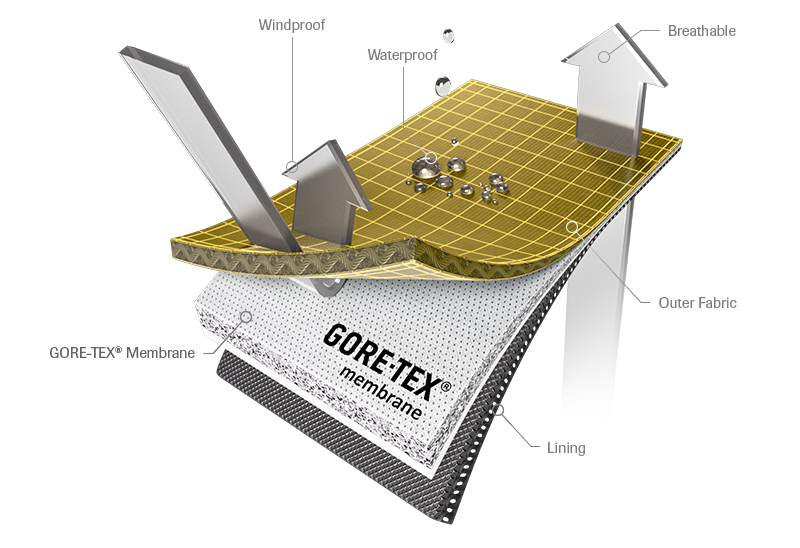

Waterproof jackets tend to consist of three layers: A face fabric, a membrane, and a liner.

The outer two layers, those being the membrane and the face fabric are bonded together. The presence and form of the third layer, usually the liner, is what determines that kind of fabric you're dealing with.

3-layer jackets are usually bonded to a slightly thicker inner layer. This is what most 'normal' waterproof fabrics consist of, especially when dealing with cycling clothing.

2.5-layer jackets combine the two outer layers with an ultrathin laminate lining. This drops weight and makes things more packable, but can reduce durability.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

2-layer jackets in general are cheaper and feature no internal lining to the fabric itself, with the mesh being 'backed' by a floating mesh sewn into the lining of the jacket as a whole.

Somewhat confusingly, some 2-layer fabrics, like the old Gore-Tex Shakedry, dispense with the face fabric instead, and are simply a waterproof membrane exposed to the elements with a backing fabric bonded on. These are superlight, tend to be extremely expensive, aren't that durable, but have the advantage of extremely good breathability and often no need for a DWR treatment.

Breathability rates (MVTR)

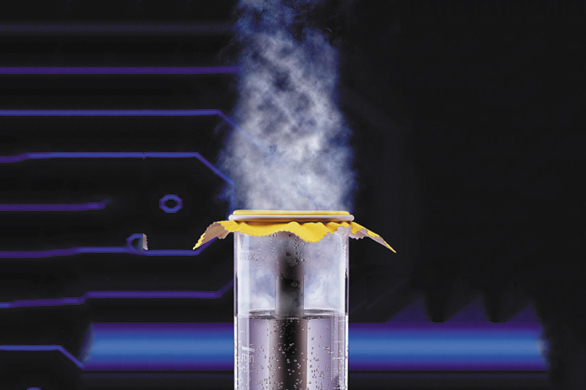

How breathable a jacket is is usually expressed as MVTR (moisture vapour transmission rate) or RET (resistance to evaporative transfer). In plain English, it’s a measure of how well sweat vapour escapes through the fabric. Higher MVTR or lower RET equates to better breathability. Sadly, different brands test differently, so take the numbers with a pinch of salt, and always refer to real world testing too.

For reference the MVTR is a measure of how much water vapour can pass through a square metre of fabric over a 24hr time period. Higher figures (20-30,000g/m²/24h) are going to be more suited to intense riding than those at the lower end (around 5,000g/m²/24h)

Cam-locked zip

A zip that stays put when you flip the puller down, preventing it from creeping open as you ride. It’s a small detail, but very handy when you’re hammering along in the drops and don’t want your jacket gradually unzipping itself. Most zips will be cam-locked on cycling clothing, but it's worth making sure.

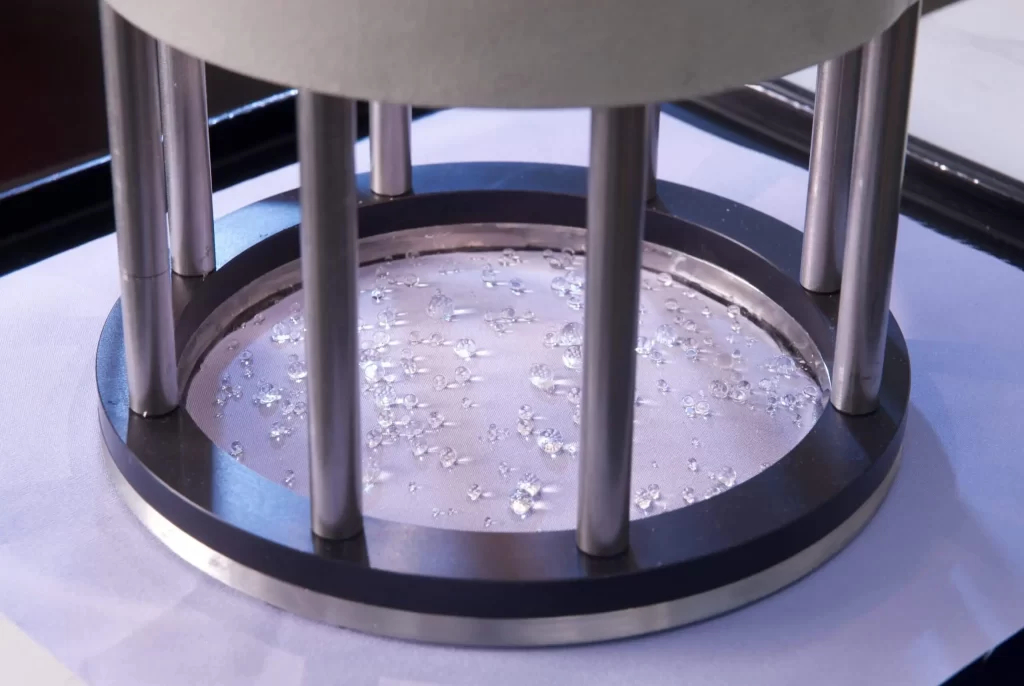

DWR

In most cases, waterproof garments are topped off with a DWR or Durable Water Repellent. It’s a chemical treatment applied to the face fabric to make rain bead up and roll off. It’s not what makes the garment truly waterproof (that’s the membrane’s job), but it keeps the face fabric from soaking up water and wetting out, which allows the garment to breathe better and stop you getting wet from sweat condensing on the inside.

A DWR is what you apply when you reproof your waterproof gear at home.

Double zip

A double zip is one that opens from both top and bottom, and in my opinion, one of the best features any jacket or gilet can have. It's incredibly useful on the bike for venting heat or reaching into jersey pockets without flapping your jacket wide open.

ePE

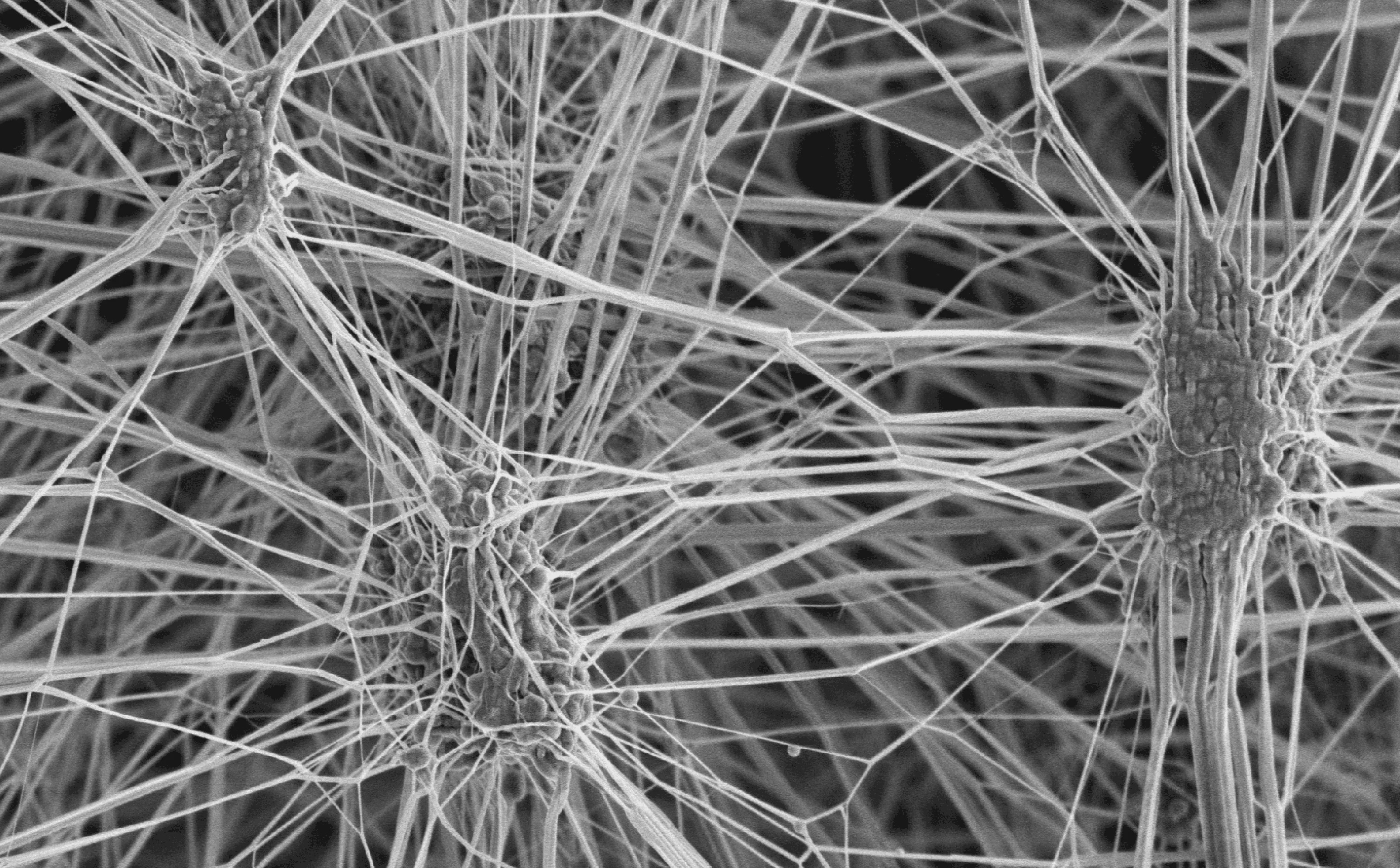

Expanded polyethylene, a newer alternative to ePTFE waterproof membranes. Brands including Gore are turning to it because it offers similar waterproofing performance without relying on PFAS that have come under environmental scrutiny.

This is what Gore uses in its latest generation waterproof fabrics.

ePTFE

Expanded polytetrafluoroethylene. The classic material used in older Gore-Tex membranes, as well as Teflon pans and plumber's tape. It’s full of microscopic pores that block rain ingress but let water vapour (sweat) out.

However, what was once the benchmark for waterproof membranes has effectively now been phased out due to the environmental and health concerns surrounding PFAS, which are used in the manufacture of PTFE.

ePU

Expanded polyurethane. Much like expanded polyethylene it offers a PFAS-free alternative to ePTFE waterproof membranes.

This is used in Pertex membranes.

Face fabric

The face fabric is the outermost layer of a waterproof fabric that you can see. Bonded to the waterproof membrane, the face fabric adds durability to a garment, and also provides the base for which a DWR treatment can be applied to.

Gore-Tex

Gore-Tex is the trade name for W.L. Gore & Associates (the parent company) waterproof membrane. It is applied to the older ePTFE membrane and the brand's latest generation ePE membranes too, and is used colloquially as a shorthand for any waterproof fabric the brand produces.

Gore-Tex fabrics

A catch-all term for waterproof fabrics which utilise a Gore-Tex waterproof membrane. There are plenty out there, though many have been discontinued since the advent of the brand's new ePE membrane. Gore-Tex Active and Gore-Tex Shakedry are probably the most commonly used in cycling applications, though there is also Gore-Tex Pro (primarily used in hiking and mountaineering applications) and Gore-Tex Paclite, a very lightweight fabric for emergency shell layers.

Gore-Tex Infinium

Confusingly, W. L. Gore & Associates also produces Gore-Tex Infinium, which used to be called 'Windstopper'. It is not waterproof, but it is windproof, and is found primarily on things like gloves and gilets.

Helmet compatible

A hood (if the jacket has one) that’s cut large enough to fit over a cycling helmet. While these are less common in the road cycling sphere, they can be handy in torrential rain, particularly on slower rides such as commutes. They are far more common on MTB-oriented jackets, as well as those geared towards climbing, hiking, and mountaineering.

Hydrostatic head

All waterproof clothing will tend to come with a hydrostatic head rating, the most common way waterproofing is measured. A lab test sees how tall a column of water the fabric can withstand before it leaks - i.e. the higher the column of water, the higher pressure of water a fabric can repel. A rating of 10,000mm (i.e. a 10m column of water can be supported without leaking) is considered 'waterproof'; 20,000mm and above means you’re well covered, even in a biblical downpour.

Mountaineering jackets can go as high as 30,000mm, but as a general rule as the hydrostatic head figure goes up, the breathability goes down, so don't fall into the trap of just opting for the largest number. Balancing both is key or you'll just end up wet from sweat.

Membrane

A waterproof membrane is essentially an ultrathin fabric which prevents water from passing through it – the starting point of any waterproof garment. They generally fall into two types: microporous and nonporous.

The former, is generally associated with modern-day jackets (ePTFE, ePE, and ePU are all microporous membranes), those that feature microscopic holes allowing air to pass through, yet stop water from penetrating.

Nonporous membranes are still waterproof, but don’t let air through either. They are literally plastic barriers like trash bags, and don't feature much outside of true emergency items and things like tents.

Packability

How small and light a garment – usually a jacket – can stuff down, usually into a jersey pocket. For us cyclists, this is often the deciding factor. A packable shell is the difference between carrying it everywhere “just in case” and leaving it at home.

There's no defined unit for this, just a sliding scale from 'extremely packable' for things like the Maap Atmos, to 'not very packable' for burlier jackets like the Albion Zoa Rain Shell.

Pertex and other fabrics

Gore-Tex doesn’t necessarily rule the roost when it comes to waterproof fabrics. Pertex manufactures 3 different waterproof fabrics: Shield, Shield Air, and Shield Pro. Polartec has it’s PowerShield fabric, which is also PFAS free, and Hyvent is often seen in cycling clothing too.

So is a Jacket made with Gore-Tex fabric better than one made with Hyvent or visa versa? Not exactly – a garments performance is governed not only by its base fabric, but by the quality of the seams, and other design features. That’s why real world testing is still so important.

PFAS

Short for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. These are man-made chemicals that were once the magic ingredient in waterproof coatings and membranes, thanks to their ability to repel water and even oil. The problem? They don’t break down in nature and have been linked to health risks, leading the EU and others to ban or restrict their use for all non-essential applications. Sadly 'staying dry on a bike ride' isn't considered essential.

The PFAS ban is a huge topic that encompasses things far beyond the fabrics used in the outdoor industry, affecting things as disparate as non-stick cookware to medical implants. If you want an very enjoyable, if somewhat bleak explainer without a load of jargon then the 2019 film Dark Waters, starring Mark Ruffalo and Anne Hathaway covers a lot of the backstory.

PFAS-free

Jackets labelled this way avoid using those problematic PFAS. It doesn’t mean they’re necessarily less waterproof, but rather means the manufacturer has switched to alternative coatings or membrane materials. A good thing for both the environment and your peace of mind.

Be aware that some products may still contain trace amounts, or can even be labelled 'Free from PFAS of environmental concern', which doesn't mean they are truly PFAS-free.

While these fabrics are certainly better for the planet, and the production of them is better for human health, they don't perform as well out on the road.

Pit-zips

Exactly as the name suggests, pit zips are extra zips under the arms that let you dump heat fast without stripping layers. They are a useful addition, especially on jackets with lower breathability ratings, but don't feature too often on cycling jackets. They reduce packability, too.

Reflective detailing

Panels, logos, or trims made from reflective material to help you be seen in low light. A small but important safety feature, especially during winter training or dark commutes.

Shakedry

Shorthand for Gore-Tex Shakedry, a 2-layer waterproof fabric widely considered to be the pinnacle of waterproof technology in terms of cycling jackets. It's ultralight, extremely breathable, incredibly packable, and as it is a PTFE membrane exposed to the elements with just a backing fabric it never needs a DWR treatment; water simply beads up and falls off it indefinitely.

Sadly it was the first fabric to be discontinued in advance of the ban on PFAS, so there are plenty of cyclists nursing Shakedry jackets year after year terrified of falling and putting a great big hole in them.

Taped seams

Even the best waterproof fabric needs help at its weakest points - the seams. While waterproof fabrics are great, to be turned into a jacket they have to be joined together in panels, and these seams can end up leaking. Taped seams seal the tiny stitch holes with waterproof tape, preventing leaks. Essential if you want your jacket to survive more than a passing shower.

Lighter jackets, or those that prioritise breathability and flexibility like the Castelli Perfetto RoS 3, will often only tape key seams on the leading edges like the shoulders and arms.

Welded seams

Instead of stitching, panels are fused together with heat or adhesive. This saves weight, removes bulk, and means fewer holes for water to sneak through. It’s the sleek, modern way of building lightweight shells and is often associated with higher end waterproof jackets as well as things like waterproof panniers and bikepacking bags.

Wetting out

Ever owned a jacket which used to bead water beautifully and now just seems to absorb it? That’s wetting out. The waterproof membrane still keeps water from coming through, but once the face fabric becomes totally saturated then your sweat cannot pass through it, meaning it condenses inside and you get wet.

This is most often what happens when people assume their jacket has 'let water through'. It hasn't, but the end result is indistinguishable.

Maintaining a quality DWR coating at home using re-proofing agents is key to your garment performing at its best. Modern DWR treatments, lacking PFAS, don't work quite as well, but with regular upkeep they still hold their own, but with enough rain there isn't a fabric out there that won't eventually wet out... except for Shakedry.

Joe is a former racer, having plied his trade in Italy, Spain and Belgium, before joining Cycling Weekly as a freelancer and latterly as a full time Tech Writer. He's fully clued up on race-ready kit, and is obsessive enough about bike setups to create his own machine upon which he won the Junior National Hill Climb title in 2018.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.