The anti-doping frontier: How the biological passport has changed pro cycling - part 1

It's 15 years since WADA rolled out the Athlete Biological Passport, regarded as the greatest development in anti-doping history. But in 2024, does it remain fit for purpose? Over two parts, Cyclingnews investigates

“Look at the climb of Alpe d’Huez in 2022. [Geraint] Thomas, [Tadej] Pogačar, [Jonas] Vingegaard, they were all there and over three minutes slower than [Marco] Pantani in 1995. And he was on a 9kg steel bike. Over the last 10 years, the sensitivity of doping and analysis has increased by a factor of 1,000, which means that you’re able to detect substances with a concentration that’s 1,000 times less than before. We are still improving the system, but I would say that if there is a doping substance in the body of an athlete, it will be found.”

These are the words of Raphael Faiss, research manager at the Centre of Research and Expertise in Anti-Doping sciences (REDs) at the University of Lausanne. The cause of Faiss’ optimism? The Athlete Biological Passport, or ABP, this year celebrates 15 years since WADA, the World Anti-Doping Agency, rolled out its “new testing paradigm”.

Over two parts, we speak to experts in the know to chart the strengths and weaknesses of the ABP, discovering why old-school EPO is favoured over the new, why blood bags remain problematic and why estate agents often look upwards when selling to cyclists. We’ll look at the present and the future, but start by looking back to see what stimulated the development of the passport…

Beating anaemia… and the competition

While an aerodynamic Greg LeMond flew past Laurent Fignon’s old-school TT set-up to win the 1989 Tour de France by eight seconds, a development in the medical world looked set to transform the lives of severe anaemics as FDA (the USA’s Food and Drug Administration) approved the use of exogenous EPO (erythropoietin). EPO is a hormone naturally produced by the kidneys that stimulates the production of red blood cells. Vis-à-vis, the recombinant version would benefit those who couldn’t generate sufficient levels on their own. And, it soon transpired, cyclists and their teams seeking a competitive edge.

While amphetamines were historically the cyclist’s drug of choice, EPO was next level as suddenly world-class climbers morphed into world-class time triallists. Athletes whose haematocrit levels – the percentage of red cells in your blood – came in at 44% could now raise it to more than 55%, even 60%. Great for endurance performance but mightily dangerous. Tales circulated of cyclists awakening in the middle of the night to perform press-ups to prevent their hearts from stopping due to high blood viscosity.

The UCI (cycling’s international governing body) took note, primarily for health (and arguably PR) reasons, and blood tests were eventually rolled out alongside a haematocrit cut-off of 50% for men and 47% for women with the first ‘no-start rule’ applied at the 1997 edition of Paris-Nice. The price of their misdemeanour? A two-week suspension. That still proved long enough to upset riders and teams who tagged phlebotomists the ‘vampires of the peloton’.

But already the teams were ahead of the game as in 1998, it became clear that the plasma expander hydroxyethyl starch (HEL) was being used to decrease haematocrit concentrations; in fact, many teams had purchased Coulter ACT haematology analysers at the beginning of the season to ensure haematocrit values measured on the morning of each race dipped under the threshold.

A year later, in 1999, Pantani was thrown off the Giro d’Italia when leading due to haematocrit levels of 51.9%. Indeed, this year's race marks another anniversary in the history of cycling doping, as it has been 25 years since that exclusion.

This, coupled with the 1998 Festina affair, left cycling’s reputation in tatters. Something more needed to be done, and it arrived thanks to a direct test for EPO developed by a French lab with the first two adverse findings in 2001.

Look indirect rather than direct

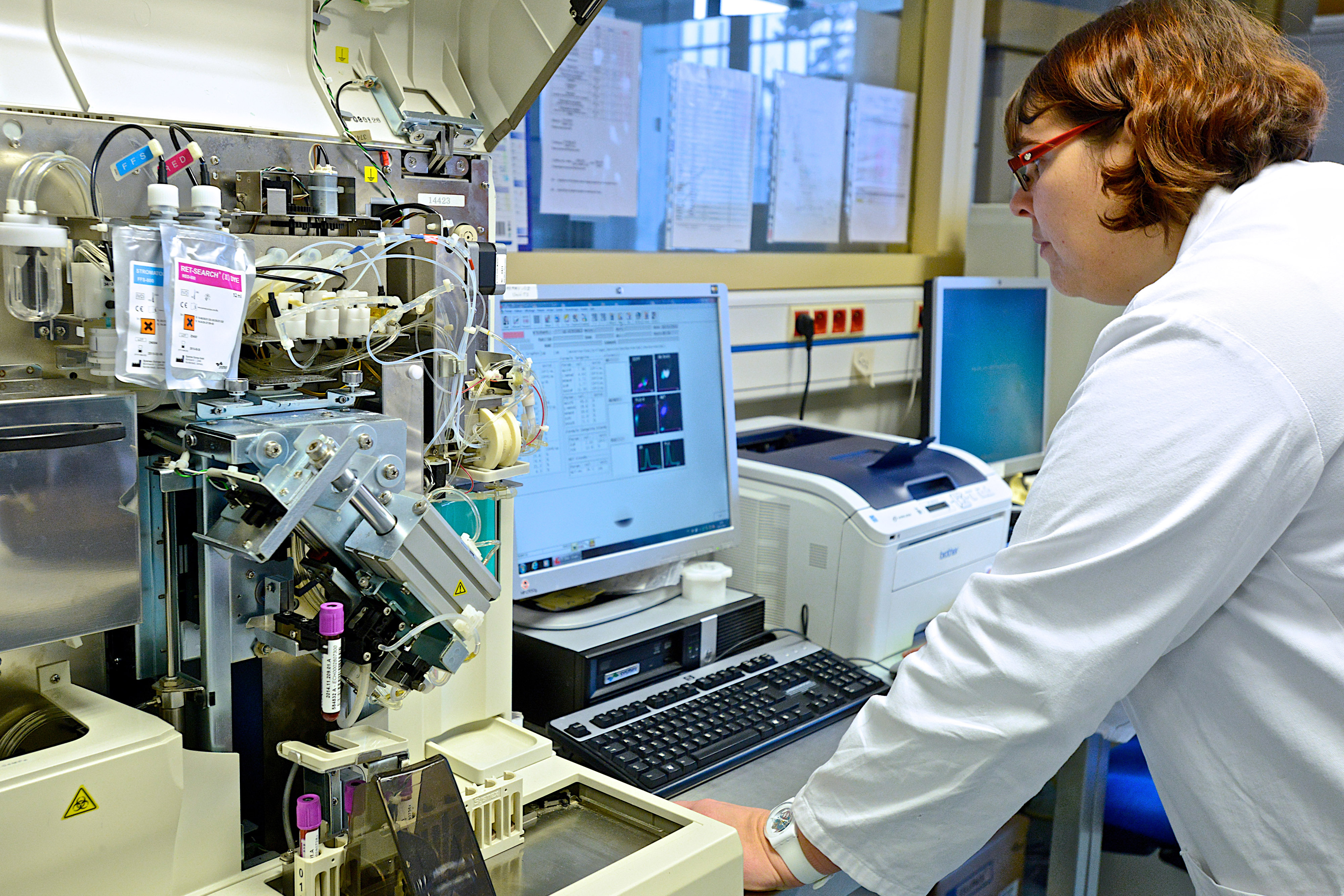

The defence had been bolstered. But there remained clear cracks. The problem with the EPO test, which is used to this day, is that for each new drug, a new test must be developed. This creates a significant lag, ensuring the cheats kept well ahead. The solution? What if instead of looking directly for drugs, you looked indirectly? To measure the physiological impact of drugs by observing trends? By examining longitudinally an athlete’s blood? This led to the development of the ABP, first used in battered-and-bruised cycling in 2008 and then rolled out by WADA a year later. Reid Aikin, deputy director of the Athlete Biological Passport at WADA, explains how it works.

“When you take EPO, you generate more reticulocytes or new red blood cells. This can skew your results above line,” says Aikin. “But there’s also an ‘off-phase’ component. When an athlete stops taking EPO, the body responds to this supra-physiological dose by shutting down the normal production of red blood cells in search of homeostasis. You then have lower reticulocyte values than normal. So, you have this booster and off-phase that the ABP picks up. When the ABP started, you were having so many athletes turn up with low levels of reticulocytes because everyone stopped taking it during competition.”

By this time, out-of-competition had cranked up, too. Both these anti-doping advancements had an immediate impact upon a rider’s blood profile, illustrated by a 2010 paper by Mario Zorzoli and Francesca Rossi entitled ‘Implementation of the biological passport: The experience of the International Cycling Union’. They observed that from 2001 to 2007, around 10% of the samples taken exhibited reticulocytes in the extreme range of either below 0.4% (off-phase) or over 2% (on-phase). On introduction of the ABP, this dropped to 2-3%. The category defined as ‘very extreme’ – below 0.2% for off-phase and over 2.4% for on-phase – disappeared entirely.

No such paper has been published since though there’s compelling evidence that the ABP has had an impact. In 2007 there were 643 positive tests. That had dropped to 146 in 2021. In 2004, around 4.6% of anti-doping samples tested were positive; in 2022, that had dropped to less than 1% (you can see the full breakdown of test volume and AAFs in WADA's published testing figures).

Evolution of the ABP

Of course, history challenges the notion that an absence of a positive test means a clean athlete. “I’ve been tested 500 times and never failed a drug test,” Lance Armstrong repeated. Often. But the ABP has evolved to target a wider gamut of performance-enhancing drugs. Originally, the ABP featured solely a haematological module. “But in 2014, a steroid module was added to the ABP that’s detected in urine samples,” says Aikin. “Then last year, we launched the endocrine module, which profiles markers of growth hormone or IGF (Insulin-like Growth Factor 1) use. This is via blood, albeit it’s a serum sample, so each module requires its own separate sample collection, though follows the same basis of observing trends over time.”

The ABP also now accounts for the performance evolution of an athlete. “It’s a project we’ve worked on with Professor James Hopker of the University of Kent, England, where we can observe ‘normal’ career progression compared to outlier efforts,” says Faiss. “This includes looking at power data. There’s much conjecture about technology fraud and motor doping. But we can look at the figures, look beyond the leading riders of a race to those who might feel they can hide in the peloton and notice that they might have needed 100 fewer watts to reach the end of the stage, meaning that they might have used a motor. Essentially, this system shines a light on any given athlete at a given time point. We don’t have infinite resources, so it’s all about pointing the light in the right place at the right time.”

The athlete system behind the passports evolved, too. WADA introduced the Whereabouts system in 2004, and it requires athletes to update their ADAMS (Anti-Doping Administration and Management System) app to state where they are one hour per day, seven days a week.

“This has been refined,” says Aiken. “We used to give details of the blood data from the lab tests but it turned out certain ‘projects’, including Aderlass [which we delve into shortly], were using this data to fine-tune their doping programmes. It’s a restriction of athlete data but they understand why.”

A costly exercise

This evolution comes at a cost. As of the end of 2021, each men’s WorldTeam and ProTeam contributed around €185,000 and €96,000, respectively, to the International Testing Agency (ITA) International Testing Agency’s, an independent body that’s led anti-doping operations on behalf of the UCI since the start of 2021. According to Iwan Spekenbrink, CEO of Team DSM-Firminech PostNL and vice president of the MPCC, aka Movement Pour Credible Cycling, this isn’t enough. The MPCC created an educational video entitled ‘Keeping the light on’, in which they raise awareness about the fight against doping.

“We as teams contribute less than 1% of our budget to anti-doping,” Spekenbrink says in the video. “Thanks to the MPCC, we’ve increased the budget so made a step but need more. Teams spend more on digital content and hospitality than doping. The biggest thing for our sport is to be credible to the world – sponsors, fans. We must increase funding.”

The UCI has increased its financial backing for its anti-doping programme by 35% in 2023 and 2024 to €10 million. Further money comes from the Tour de France ($214,000), while the Giro and Vuelta contribute $181,900 each. WADA’s annual budget is just under $50 million.

That increased budget is needed as testing isn’t cheap. At the beginning of the programme in 2008, the UCI planned to collect a total of 10 blood and four urine samples for each athlete both in- and out-of-competition. In 2009, this would remain for new riders entering the programme, while the older ones would undergo a reduced number of tests (six blood and three urine tests), unless other reasons (i.e. abnormal profiles, sport performance) dictated otherwise.

Now, the aim of the ABP is an average of three tests per year, with some riders tested once, some more than 10. This tends to vary depending on success, with the leading riders tested at least three times during a Grand Tour. Complete two Grand Tours in a season, and that’s already six without taking into account other in-competition and out-of-competition tests. If you’ve raced for many years at the top level, your passport will have ballooned to over 130 samples that are then kept in storage, albeit a bugbear of many in anti-doping is that GDPR stipulates the data can only be stored for 10 years.

With the passport, it takes a long time to see if there’s something wrong, to spot trends. It can take several seasons to see if a rider’s profile potentially says that he or she is cheating

Testing frequency also depends on which country you’re based, says Aiken. “When we talk about 15 years of the passport, there's still a real gradient of experience with some countries only implementing improved anti-doping measures in the last few years,” he says. There are 30 WADA-accredited laboratories worldwide but only one apiece in South America and Africa, meaning unless a rider is training in Rio de Janeiro or Bloemfontein, their sample will have to travel a significant distance at great expense.

Then again, if a rider is training in a remote location, this arouses suspicion at the UCI, whose ‘Regulation for Testing and Investigations’ lists a number of factors where riders should be tested more frequently, including “moving to or training in a remote location”. Other factors include “nearing the end of a contract” and “withdrawal or absence from expected competitions”.

Understandably, what it doesn’t list are the weaknesses of the ABP. Roger Legeay is president of the MPCC, creating the organisation in 2007 off the back of ‘another’ doping scandal, Operacion Puerto. “The passport is a great tool for the fight against anti-doping but has one clear problem,” he says. “With the passport, it takes a long time to see if there’s something wrong, to spot trends. It can take several seasons to see if a rider’s profile potentially says that he or she is cheating.”

It’s a criticism Aiken counters: “You can flag outliers even on the first test as you can compare with that athletic population and say, this is highly abnormal. In fact, we often flag up an athlete’s data after their first test because they don’t think they’ll be under scrutiny. In general – and this is published WADA stats – almost 45% of EPO positives are with the first EPO test of an athlete. Of course, when it comes to the ABP the athlete’s limits narrow more over time and it becomes more personalised to them, becomes more sensitive.”

Importance of Aderlass

Of course, like any tool, the ABP is only as effective as the experts who use it. And that means learning. Which is why Aderlass provided much insider material for the anti-dopers to pore over. Operation Aderlass was one of the highest-profile doping scandals of recent years and was an investigation in Austria and Germany into doping practices carried out by German physician Mark Schmidt. Numerous cyclists and cross-country skiers were implicated.

On March 3, 2019, Stefan Denifl, who last rode for Aqua Blue Sport the season before, confessed to blood doping under the assistance of Schmidt, while a day later, Georg Preidler, who was riding for Groupama-FDJ at the time, also confessed to having had two blood extractions with Schmidt in late 2018 but denied ever actually doping. Both were handed four-year bans.

The abiding image of the Aderlass scandal, however, is one of Schmidt’s clients, cross-country skier Max Hauke, caught red-handed by the Austrian police in the middle of a blood transfusion. One of the police filmed the episode.

“Hauke recently presented at an anti-doping conference where he explained some of the tactics employed by doping athletes to beat the testing,” says Faiss.

“One of the simplest involved living on the top floor of a high-rise apartment block. When a doping officer rings the bell, you have more time to rapidly drink saltwater that impacts your plasma volume [of which we’ll elaborate on shortly]. You then play dumb to buy more time and try to charm the officer before telling them that you’ve just trained hard, which means you need to wait for two more hours as hard exercise can impact the results.”

“Hauke also told us that he was using blood transfusions and growth hormone rather than EPO because Dr Schmidt told him he’d be caught if he took EPO,” Faiss adds, stating that this was before the endocrine module of the ABP was brought in last year.

Faiss also revealed that there’s evidence that athletes using EPO are reverting to the original product as the latest generation’s designed so that severe anaemics would require fewer injections so it lasts longer in the body. Great for them, not for dopers.

One of the simplest involved living on the top floor of a high-rise apartment block. When a doping officer rings the bell, you have more time to rapidly drink saltwater

How they take EPO can vary, too. “Athletes take the same substances but in different forms,” the head of science and medical at the ITA, Neil Robinson, explains in the ‘Keeping the light on’ video. “When I began my doctorate, athletes were taking EPO subcutaneously. It’s the best and cheapest way to make sure it works. But it’s detectable. So, dopers went from subcutaneous to intravenous. It’s less effective, offering fewer benefits but also less detectable.”

Blood transfusions seem medieval compared to EPO, but, says Faiss, there’s a good reason they’re still used. “Taking your blood out, putting it in the fridge and reinfusing it, compared to the quantity that you have in your own body, that’s not much, so that’s a challenge. Historically, we’d look for plasticisers, which are small plastic particles from the pouch that were detectable in the blood. But then athletes started using pouches that didn’t release any plastic particles.”

The major challenge: micro-dosing

That 2010 paper by Zorzoli and Rossi revealed the behaviour change stimulated by the ABP. Which brings us to micro-dosing, more specifically, micro-dosing of EPO. As the name suggests, this simply involves injecting smaller quantities of EPO that are harder to detect by the ABP but still high enough for a performance boost. A 2022 paper, ‘Altitude and Erythropoietin: Comparative Evaluation of Their Impact on Key Parameters of the Athlete Biological Passport: A Review’ by a team led by Jonas Saugy, showed that traditional EPO resulted in haemoglobin and reticulocyte levels that were 1.7 times higher than micro-dosing while haemoglobin mass was four times higher. Despite that, one Danish study showed a 5% increase in time-trial effort after micro-infusion.

“In a sense, I’d say the ABP’s working because it’s forcing athletes to change their attitude towards doping, which is certainly less dangerous,” says Faiss. “Imagine you’re in a car travelling from A to B. You know there are never police on that road so you can drive really fast. But what happens when you know there’s a road with a speed camera on? You know you must reduce your speed. Okay, you may drive slightly over the limit, but not fast enough to be flashed. It’s safer and ultimately health of a rider is the number one concern.”

Both Aiken and Faiss concede that micro-dosing EPO is problematic for anti-doping organisations, especially as its blood profiles are very similar to an environment increasingly inhabited by the world’s finest cyclists. That 2022 paper by Saugy showed that an athlete’s blood profile when micro-dosing was “hardly distinguishable from those identified after hypoxic exposure”. In other words, when an athlete hits altitude (legal), the endurance-friendly adaptations are at a similar level to micro-dosing (illegal).

“It’s true that differentiating the two is absolutely a challenge in anti-doping,” says Aiken, “so when athletes combine the two, it can cause confusion. We've invested heavily into research in this area. It’s high priority for WADA.” A series of papers spearheaded by Nikolai Nordsborg of the University of Copenhagen is investigating different markers to separate the two, including genetic markers. “But it’s worth speaking to Laura Lewis,” says Aiken. “She’s an expert on the haematological module.”

And so we did. What Lewis told us left us feeling reassured and concerned in equal measure. Find out next time about the nefarious performance benefits of extracting blood at altitude, why the future of anti-doping is artificial intelligence and how DNA testing lay behind the case of the Kenyan doppelganger.

Thank you for your Cyclingnews subscription. We use our subscription fees to be able to keep producing all our usual great content as well as more premium pieces like this one. Find out more here.