Jonathan Vaughters: The Sleek Geek

Part I: When I was young and carefree

As a young bike racer, he was up against some of the best graduates American cycling has ever produced. When he turned pro, he was scorned by many of his peers for not being "part of the program" - then soon found himself caught within that insidious circle.

He left cycling because he got tired of not using his brain and sick of where the sport was and where it was headed.

But now, in a team where results matter second to the method used to achieve them, ironically, he heads one of cycling's most successful squads, which upon its Tour de France debut in 2008 was called "the Clean Team"... and very much still is. Anthony Tan charts the rise and fall and rise again of Jonathan Vaughters.

When I was young and carefree

Do not scorn the weak cub; he may become the brutal tiger.

The Mongolian proverb appears at the start of the 2007 film Mongol, the first in a planned trilogy about the life of Temüjin, the name given to the young Genghis Khan, who began life as a slave but at the height of his reign had conquered half the world, including Russia.

Jonathan Vaughters' life does not mirror that of Khan's by any means. But in terms of his life in cycling, the proverb holds some truth.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

His is the story of a naive, geeky, bespectacled guy who, as a bike racer in Europe, often found himself ostracised despite his obvious talent - but seven years after retirement, owns and operates one of the most formidable teams in cycling, and if one judges a squad by its success, popularity and clean image, successful also.

"Our objective really, is to become the number one ranked team in the world," says Vaughters, whose team was ranked seventh-best among 18 ProTour teams (now called ProTeams) at the close of the 2010 season. "To do it while continuing the anti-doping program of Don Catlin that we've always had in place, and meeting the ethical guidelines that we've set for ourselves from day one.

"Our goal would also be to have the best development program in the world and the best women's team in the world. So I think those are the three things that we aspire to at this point in time. I don't know if those require us growing - they just require us to do what we're doing better than what we're doing right now."

A frame like Fausto Coppi

Born and raised in Denver, Colorado, just east of the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains, and the only child of an attorney father and speech pathologist mother, Vaughters' stringy boyhood frame appeared not at all suited to a career in sport, admitting to being hopelessly uncoordinated.

In his teens, however, he discovered a knack for go-karts and then bicycles. Blessed with the body of a climber, a tactician's cunning and a pair of lungs that make his chest protrude like the great though tragic post-war cycling hero, Fausto Coppi, he was soon thriving as a racer.

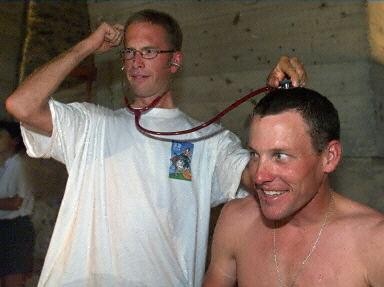

But as a member of the junior US national team he was in elite company: Bobby Julich, Kevin Livingston, Lance Armstrong, Tyler Hamilton, Fred Rodriguez and George Hincapie were a few of his enormously talented peers. "People come up to me and say: 'I guess you won a few junior national championships'," Vaughters told me in an interview in 2002, soon after he decided to turn his back on a cycling career in Europe because "the financial rewards of it weren't enough for me to keep beating myself up to do something I'd already done before".

"I never won a junior championship!" he protested. "The best I ever did was third in the time trial - and if you look back at it, you can see why - the competition was unbelievable, and it was a really talented generation."

Here is perhaps where the Mongolian proverb and the life of Jonathan Vaughters intersect.

At the start of 1994 season, Vaughters, 20 years old at the time, began his professional cycling career with a Spanish-based outfit called Santa Clara and run by Jose-Louis Nunes; a devout Roman Catholic and member of Opus Dei, which essentially funded the team. For the three years he was there, Nunes would deliver sermons on the evils of doping - paradoxically, at a time when the practice was never more rife - believing this small upstart could 'change cycling'.

"But we got killed!" Vaughters said. "All the time - I mean, we were the worst team by far!"

"When I look back on it, I guess it could be one of the reasons why I lost some of the motivation because my first three years were such an intense struggle. I was never even remotely competitive... the only thing that I was competitive with was myself, trying to better what I had done two weeks before.

"I was always at the risk of getting dropped so early in the race or trying to make the time cut - it was always such a constant struggle, hanging on for dear life."

1996: Not a great time to conquer doping

Some 15 years later, on the eve of the 2008 Tour de France, his first outing at the race as general manager of what was then Team Garmin-Chipotle, considered by many to be the staunchest anti-doping crew on the block, he told Paul Kimmage from the London Sunday Times: "He [Nunes] was out to conquer doping... Well, I don't think '96 was a really great time to do that.

"My teammates thought it was absolutely ludicrous that we didn't dope on this team. We got made fun of, quite frankly, by some of the other riders. Mentally, the saving grace for me was that I still had nothing better to do with my life. I was the infinite optimist. 'I'm going to improve. Things will get better. They will soon develop a test for EPO'."

He would have to wait; it wasn't until the 2000 Olympic Games in Sydney that a urine test to detect EPO became available, and four years later at the Athens Games till a validated test for homologous blood transfusions was used. Still no check exists for detecting an athlete that has taken then re-injected their own blood, yet evidence of autologous blood doping dates back as far as 1984.

(In Francesco Moser's successful 1984 world hour record attempt, cycling trainers Francesco Conconi, Aldo Sassi and Michele Ferrari 'prepared' Moser using autologous blood transfusions. In an interview with La Gazzetta dello Sport this October, Sassi said of his actions: "According to the codes and procedures of the time, that wasn't doping but it did modify fair play and could have been a health risk. We knew that it was a short cut, a trick. At the time, the autotransfusion was considered an application of science in sport." He also told US magazine Bicycling: "The ethical perception of doping then was not the perception we have today. What today is doping, was in that period, science.")

When Santa Clara went belly-up, Vaughters returned to the US in 1997 and racing domestically, found it to be "a thousand times easier. I won everything that year... the national time trial championship... the national racing calendar points series... I was the star rider of the domestic racing scene."

Hints he may have dabbled

His string of performances earned him a two-year contract at US Postal, team of the post-cancer Lance Armstrong. During that time, there were moments he excelled: in 1998, first overall in the Redlands Classic, including two stage wins; in 1999, first overall in the Route du Sud, the Mount Evans hill climb, and second overall in the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré including the win he's best known for, a time-trial victory to Mont Ventoux.

But for the most part, Vaughters told me in that August 2002 interview, it was still a struggle. And while he's never publicly admitted to doping (although he's admitted to seeing such practices first-hand) there are hints he may have dabbled.

"It wasn't just me [who struggled]. Kevin [Livingston] and Bobby [Julich] started out on Motorola, which was a bigger team, but they would be in the same situation I was; I can remember one of my first Tours where it was just Bobby and I - we were the last two guys - and this is the guy that ended up coming third in the Tour de France four or five years later (Julich finished third in 1998).

"But it was always like that - Kevin and I would always be struggling, struggling, struggling, but," he said perhaps somewhat tellingly, "I don't know what happened over the years - either the racing got slower or we got faster."

Then this rather, take-it-how-you-want-it sentiment to Kimmage, who suggests in the face of the devious practices going on around him, his win atop the Ventoux in '99 was extraordinary - "massive", he says.

"I felt okay. I wasn't ecstatic," he demurred. "Well, for sure, it was the best form of my life as a bike rider, but I wasn't... I was just sort of... I will leave it at this; I wasn't overly pleased with that victory. It was interesting to me. It answered a lot of questions. But it wasn't the most ecstatic moment of my life by any means."

Sting in the tale, but a long time coming

Things become blurrier still when Vaughters joined French team Crédit Agricole at the start of 2000.

Kimmage wrote: "For the first time in six years, Vaughters had found his natural home. He liked the manager, Roger Legeay, and his way of doing business. The 18 months that followed were the happiest of his career... until the sting in the tale at Pau," the latter in part referring to his infamous wasp sting, which swelled his right eye to golf ball proportions, a week before he was due to finish his first Tour de France in 2001, and being told by the team doctor that if he took a cortisone injection and was tested, he'd be declared positive. He chose to quit the race.

(The spelling of 'tale' is not an error; as Kimmage wrote, it refers to an incident with an unnamed though "famous rider" the morning following his decision to abandon: "Poor Jonathan and his stupid little team," the rider spat. "What the f*** are you like? If you were on my team this would have been taken care of, but now you are not going to finish the Tour de France because of a wasp sting."

Said Vaughters: "I thought, 'F***! Here I am, on this team that is really trying to stick by the books and this guy is making fun of us for playing by the rules'. My heart just left me after that. It just made me sad, just irrevocably sad. I raced [the following year] in 2002 but that was the moment that effectively ended my career. Phew! I was done. I didn't want to race any more. It just didn't seem to matter to me after that.")

But the way Vaughters told his experiences at Crédit Agricole to me, just weeks after leaving, goes against the grain of Kimmage's 2008 story.

Asked if was to do with the entrenched, old-school European culture of the team, having come from two years at US Postal, he said: "I never minded the foreign culture part... But the only guy I really had a friendship with was Chris Boardman, and he left after my first year there.

"It [Crédit Agricole] was a team where everyone kinda showed up, did their job and went home. I mean, the communication between the French riders and the foreign riders is really minimal and the environment to really perform was never really there. There was never a pathway saying, 'If you do this, you'll do really well'.

"It was Roger [Legeay] saying: 'We've got to do well, hurry up and do well', and getting really stressed about the results not being there and not defining a clear method to follow to enable us to do well. So it was kind of a stagnant environment - I felt like my last couple of years there was a matter of waiting for my paycheck and the end of every month, and that was the only thing that was making me turn up."

Vaughters also told me his angst had been grinding at him long before he joined Crédit Agricole. "I spent nine years in Europe as a pro, and I also spent nine years being homesick," he said.

"Every once in a while, I would just completely flip out and realise all I've been doing is riding a bike for the past three or four months, and when everyone was heading out to do their six-hour training ride I would say, 'I'm not going today'.

"I'd head down to the local art supply store and start whippin' out oil paintings for three or four days in a row to just settle my mind back down to sanity... And I think Christian [Vande Velde] always thought that was funny but at the same time he'd realise, well, that it was also completely understandable."

An inkling of what lay ahead

In 2002, he also recalls having many conversations with Kevin Livingston - "he and I talked all year" - but the thing was, whenever they talked, they almost never spoke about cycling. "Whenever we were in a race talking, we were talking about things outside of cycling, like, 'If I started this company, or went into this or whatever,' - we were constantly talking about how to make a living after pro cycling was done; I don't think we ever discussed how we were actually doing in the race!" he laughed.

"That's what kills you. Your brain goes stagnant for so long that eventually you just can't handle it anymore and you go, 'I've just got to do something intellectual', as opposed to just physical."

Notably, though, jaded as he was, Vaughters appeared to know where his strengths lay. "I don't know why, but I have an interest teaching a little bit in the near future. Coaching really appeals to me. I think I've got a unique combination of actually having done it and done well, as well as the intellectual and analytical capacity with my knowledge of anatomy, biochemistry, and endocrinology - and I've been able to successfully combine those two worlds.

"And I don't know if that's ever been done before. You've got some top sport scientists out there who are training some big teams, but they don't really have a true feel of what it's like to ride a 220-kilometre race at 48 kilometres an hour. I do - and it's something that I really hope for when I make the transition out of racing to do well in.

"I've got big ambitions as far as training goes and like I said, with that combination, I may not have been able to have been the best professional cyclist in the world, but I really do think I could become the best coach."

In Part II, Vaughters talks about what has happened since 2002: the establishment of his team from fledging development squad to cycling superpower and the environment in which it now exists.