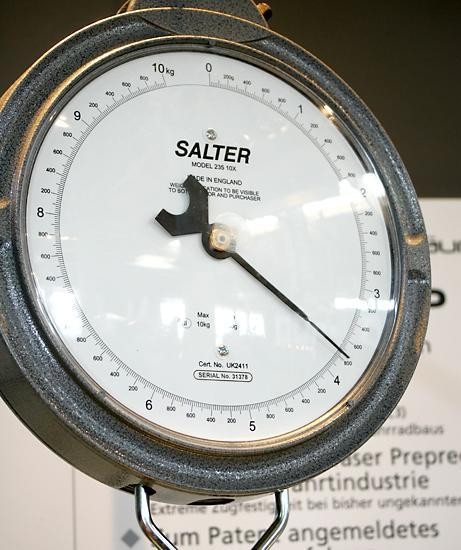

How light is too light?

The UCI considers that the answer to that question is "less than 6.8kg", which is the minimum...

Tech analysis, November 13, 2004

How light is too light?

The UCI considers that the answer to that question is "less than 6.8kg", which is the minimum permitted weight for a bike used in UCI-sanctioned races. But as bikes that weigh less than the UCI limit start to appear in the shops, John Stevenson asks a number of manufacturers whether it's time for a rethink.

In our daily battles to go faster and further on our bikes, cyclists face two main natural enemies: the air and the force of gravity. It's hard to do much about the air, aside from heading to Mexico City or La Paz for record attempts. You can't avoid gravity either (it's not just a good idea - it's the law) but you can give it less to act on: a lighter body or a lighter bike. Lighter bodies require work: training and self-sacrifice. But a lighter bike, ah, a lighter bike you can just buy. Walk into a bike shop, drop a couple or three months' salary and you can roll out on a rig that weighs the same as Lance Armstrong's or Ivan Basso's; or even less.

This is why cyclists are so obsessed with bike and component weight - it's a factor that makes a direct difference to performance, especially when you're talking about climbing hills, and it's something you can improve without any effort beyond the pain of the eventual credit card bill.

Seeing the way bikes were getting lighter and lighter and more and more expensive, the UCI in 2000 passed a rule limiting the weight of bikes that could be raced in UCI-sanctioned events. That limit still stands: 6.8kg, or 14.96lb. At the time, it wasn't an unreasonable measure. It was possible to build a bike that light, but it involved either spending silly amounts of money or cutting corners on component durability that also cut corners on safety.

The rule was also justified on the grounds of the philosophy of sport, as laid out in the UCI's 1996 Lugano Charter . "The UCI wishes to recall that the real meaning of cycle sport is to bring riders together to compete on an equal footing and thereby decide which of them is physically the best," the organisation wrote in 1996. In imposing the weight limit the UCI evoked this philosophy, saying "the Management Committee wants to avoid any trend towards excess which would not be in line with the policy stipulated in the Lugano Charter."

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

That was then

The problem is that what was once excess is now close to being mainstream. For 2005 several manufacturers are offering off-the-peg bikes at or below the UCI weight limit, and those bike manufacturers that sponsor racing teams find themselves in the peculiar position of being able to sell bikes to the general public that their sponsored riders can't race.

It's a situation that has caused considerable frustration and mystification among bike manufacturers in the last couple of years. Several pro team bike sponsors we contacted would like to see the limit lowered, abandoned altogether or replaced with tests that determined a bike's safety based on more than a seemingly arbitrary number.

Scott, bike sponsor of the Spanish Saunier Duval team is one of the companies at the forefront of pushing the weight limit. Scott makes one of the few sub-900g frames, the CR-1. While you still need to spend significant money to build a sub-6.8kg bike from a CR-1, you don't have to go insane with one-piece saddle/seatpost combos or wheels that require a second mortgage on their own.

Nevertheless, Scott is extremely confident of the safety of the CR-1. Scott Montgomery, head of the recently reopened US division of Scott, told Cyclingnews, "We at Scott wish the UCI would adjust the weight limit downward as we know a 14lb bike is lighter and thus faster and - under our unique process - is also extremely safe. We think faster racers are more exciting for fans, and most appreciated by riders. Though, we do think there are bike companies out there who have no idea about the requirements, demands, torques, and needed standards for carbon, so we understand the UCI's go heavy - and slow approach. As long as the weight stays at the current level we will do the necessary steps to add weight to the bikes to stay at the 15lb. level."

Legalise my...

As sponsor of the Saeco team, Cannondale has been practically waging a one-company campaign against the weight limit for the last couple of years. In 2003 Saeco riders sported 'Legalise my Cannondale' jerseys at the Giro and Tour de France, and Gilberto Simoni started a stage of the Tour with weights attached to his bike to bring it above the limit. Saskia Stock, Cannondale's European VP of marketing at the time, said "we'd like the UCI to consider changing the basic regulation. We'd certainly support a rule that protected riders by requiring frames of any weight to meet sensible strength and durability standards. But to select an arbitrary minimum weight requirement discourages innovation, and it does little to protect the riders."

More recently, Cannondale's Rory Mason told Cyclingnews, "The current weight limit really hinders the development of new technology, as it creates a perception that if the world's top racers can't use it, then the public will not buy it. However, it is Cannondale's sincere belief that testing of products is what really matters and not just an arbitrary weight limit. The UCI's wheel approval tests and helmet restrictions are in fact proof that the UCI understands the importance of product testing and approval."

And so it goes on. None of the bike sponsors we contacted was wholly in favour of the current limit, though Specialized's Sean McLaughlin said he could see both sides of the argument. "On one hand, I think that the establishment of a minimum weight is reasonable," said McLaughlin. "It helps somewhat to level the playing field and arguably promotes a certain degree of safety."

While there are now bikes out there that dip under the limit, Mclaughlin pointed out that they're not exactly common. "The current limit is still pretty light. A 15lb / 6.8kg complete bike that can withstand "real world" riding remains a rare and expensive animal. It's one thing for a professional team to equip a bike for one stage of a given race. It's another for a paying customer to part with five, seven, ten thousand dollars or euros for a bike that will potentially (and hopefully!) see tens of thousands of miles or kilometres of use."

Nevertheless, for Specialized, customer demand - the power of the market - will determine the bikes the company develops and sells, and not the UCI's rules. "As a bike manufacturer, we'll continue to develop the lightest possible frames that deliver the ride qualities, performance, and durability that our athletes and our customers desire," said McLaughlin. "To stop innovating because we've approached or breached an arbitrary limit would be both counter to our desire for continuous improvement as well as a rather large business blunder."

Trek's "random number"

Business considerations no doubt also motivate Trek Bicycles, whose sponsorship of Lance Armstrong's US Postal Service team has been hugely successful for the company. Trek has been part of a concerted effort to provide Armstrong and the team with the best possible, lightest bikes for the last few years. Trek hasn't made a big fuss about its bikes being illegally light, but has quietly got on with meeting the regs and - rather successfully - giving Armstrong and the team the bikes they need.

Nevertheless, Trek's not happy with the situation. Scott Daubert, Trek's team liaison, told Cyclingnews, "Trek would like to see a change in the minimum bike weight and we question if it needs to exist at all. Having a minimum weight seriously impedes product advancement. Also it seemingly is based on a random number and is in no way a reflection of bicycle safety."

Is it safe?

Daubert isn't the only one to question the equation of weight with safety. One company that has been pushing the weight envelope in recent years is Cervélo, but as well as building light bikes, Cervélo has worked hard to ensure its bikes are also durable and testing by the German EFBe lab confirms that the Cervélo R2.5 used by CSC this year is plenty tough.

"Cervélo would welcome a system where bikes need to pass certain durability and strength tests instead of a simple weight test," Cervélo's Gerard Vroomen told Cyclingnews. "In the 2004 Tour, there were frames with double the weight and half the strength of the Cervélo R2.5 Bayonne, yet somehow the Bayonne was not allowed to be used."

T-Mobile's bike sponsor Giant has also found itself probing the weight limit in the last couple of years. "Our TCR 100 special edition of 2003 was 6.5kg in a medium and we only used normal commercially available components - so it's a valid point," said Giant's Tom Davies. Davies also wants to see the UCI tackle quality rather than quantity, as it were. "I think there needs to be a standard 'quality' certificate (like the DIN Plus standard)," said Davies, "so that as long as you have this then the weight can be lower."

One concern for Davies is the less-experienced composite bike makers that are currently popping up. "I fear with so many new composites coming onto the market we may soon face a durability problem," he said. "A stringent quality certificate (which tests for strength both vertical and lateral forces on a bike frame) would be a starting point. Since 6.8 kilos is really an arbitary number; a bike can very safe at 5.5 kg and equally very unsafe at 8.5kg if it is constructed of sub standard material."

Man on the moon

Orbea's Joseba Arizaga is puzzled that the weight limit only applies to road, track and cyclo-cross bikes and not to mountain bikes. "If the weight limitation concerns safety, what about mountain bikes? I follow our MTB team and nobody is taking care of MTB bikes," he said. "These races are much more dangerous than road and mountain bikes contain much more technical elements that a road bike, so safety is more important than on road."

Aside from safety concerns, the issue for Arizaga is less one of being able to sell the bikes his sponsored riders use as the way that "development is limited by the UCI. Look at Hour Record bikes. How is possible to ride traditional bikes in the 21st century? Man can get to the moon, but not use a revolutionary bicycle!"

The UCI view

In the face of an increasingly unpopular regulation, then, with bike sponsors of no fewer than seven of next year's Pro Tour teams unhappy with the weight limit rule, what's the UCI's position? Perhaps surprisingly, it's not as uncompromising as you might expect.

The UCI's technical consultant Jean Wauthier told Cyclingnews, "A technical rule is not only technical. It also has elements which take into account higher interests. Technology is subordinate to a project and not vice versa."

Wauthier took the time to explain how the rule came about. "We have had talks with the most representative of manufacturers, namely those that have study and research centres and who use ISO quality systems for their products," he said. "They have given us a weight of 7kgs below which it was becoming difficult to go any further because of technical considerations like rigidity, road-holding and stability, ultimately concerned with safety. We allowed a slight margin of tolerance by fixing the minimum weight at 6.800 kgs. We have also consulted users and riders in competition."

Wauthier added that a UCI survey when the rule was introduced had found that most bikes use in road and track racing weighed above 7kg and that surveys at the last track and road world championships had found the same. "Apart from exceptions (like a mountain time-trial) the usage value does not suggest a lowering of the weight of bicycles."

"Nonetheless," said Wauthier, "our rule is not a dogma. If there are objective elements that can justify a lowering of the minimum weight, we need to be shown what now invalidates what was inconceivable before, although to my knowledge we have not yet recorded any significant technological advances."

Although bike weights have crept down over the last few years, it's been a result of the gradual application of existing materials technologies - and especially composite technologies - to more and more areas of the bicycle, so it's true that there has been no great leap. Wauthier added, "technological progress (if there is any progress) is not only measured by the reduction of the weight of a bicycle. It includes other more important criteria. In 1999, two or three manufacturers could already produce bicycles weighing 6.500 and 6.400 kgs but what prevented them then, to their credit, was not a UCI rule (which did not exist at the time) but technical considerations."

Time for a change?

However, the UCI does have a mechanism for rules such as the weight limit to be changed. The relevant regulation is UCI rule 1.3.004, which says:

No technical innovation regarding anything used, worn or carried by any rider or other license holder during a race (bicycles, equipment mounted on them, accessories, helmets, clothing, means of communication, etc.) may be used until approved by the UCI Executive Committee. Requests for approval shall be submitted to the UCI before 30 June of any year, accompanied by all necessary documentation. If accepted, the innovation will be permitted only as from 1 January of the following year.

In other words, if you want to introduce a technical innovation such as a sub-6.8kb bike, you have to apply by June 30 of one year for a successful application to cause a rule change for the following year. While the policy of the Lugano Charter and the UCI's equipment philosophy as manifest in the Hour Record bike regulations would seem to make an application unlikely to succeed, the ball is very much in the court of bike sponsors and teams to get the rule changed.

Have your say

Should the UCI weight limit be changed, abolished or replaced with a safety certification system? Or is it a good thing that keeps competition between riders and stops technology from taking over? Tell us what you think.