How did watching cycling become so expensive, and what does it say about the business of pro cycling?

As the cost of watching cycling on TV increases, Cyclingnews analyses the driving forces behind the change and where all the money ends up

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The summer is fast approaching, and for cycling fans in 2025, that means one thing: facing the increased cost of watching the sport's tentpoles, the three Grand Tours. Across Europe, Canada and the US, watching cycling is only becoming more expensive.

The situation in the UK has made the headlines because this summer’s Tour de France will be the final edition to be free to air on ITV4, and after that fans will need a £31-a-month TNT Sports subscription to watch most events, with the currently-running Giro d'Italia already behind that paywall – but it's not unique to Great Britain. Whether it's Eurosport, Max or FloBikes, cycling is increasingly going to subscription-only services, which are getting more expensive.

For ardent fans, it's a cost that many have little choice but to absorb, save for missing out on watching the key events of the calendar. But what is behind the changes, and where does TV subscription money go?

Though TNT Sports owners Warner Bros. Discovery are now the sole owners of Tour de France rights in the UK, ITV's decision not to renew their contract with the Tour was not directly related to that, and the loss of free-to-air coverage was a long time coming.

Ned Boulting, who has been part of ITV’s coverage of the Tour de France since 2003 and will commentate alongside David Millar in July for the last time on the channel, says the more casual audience has been ebbing away for many years.

"For 99% of the British public, the Tour de France is the only cycling race that exists, and even that is of secondary importance compared to the Olympics. The audience peaked with the Grand Départ in 2014 [when the race began in Yorkshire] and ever since then it’s been in slow decline, while the cost of re-signing the rights has grown much faster," said Boulting.

As a result, ITV failed to make a bid for the new contract, and neither the BBC nor Channel 4, which initially brought highlights of the Tour to the UK in 1986, were interested, as the audience is provably small.

“I know that the BBC have from time to time quite coveted the idea of showing the Tour, but they simply don’t have the bandwidth or the channels to stick up an event that happens every day for three weeks," Boulting added.

Although the rights holder, the European Broadcasting Union, is a club for public service broadcasters, it opted to sell the rights to TNT Sports, a pay channel created by a merger of BT Sport and Eurosport. It made a loss of £34m in the year to July 2023, according to Companies House filings. The actual race footage will be provided by France Television, as before.

Warner Bros. Discovery, the parent company of TNT Sports have been working on streamlining their offering in recent years, shutting down GCN+ and Eurosport in the UK, and this consolidation is part of the reason why cycling is now in the main TNT subscription, rather than a cheaper Eurosport package.

Of course, in other sports, subscription fees of £20-40 a month are not rare. When the Premier League took the plunge into pay television at its birth in 1992, the £304m paid by BSkyB was the first step in its march to worldwide popularity, but for cycling broadcasters, the imposition of an expensive paywall is a sign of weakness, not of strength.

Rupert Murdoch, who had satellite dishes to sell, bet correctly that football fans were prepared to pay way more as subscribers than the rate bid by the incumbent broadcaster, ITV. The number of matches on air soared, and the quality of the coverage was transformed. There is, unfortunately, no such buzz around cycling.

Darach McQuaid, chief executive of Oakbrew Swiss, who brought the start of the Giro d’Italia to Ireland in 2014, knows a thing or two about the delicate art of creating and funding cycling events. He has also brought Saudi Arabian funding into a WorldTour team - with Team Jacyo AlUla sponsored by the Royal Commission for AlUla, an arm of the Saudi Arabian government.

McQuaid entered the business during the lean times of the 1980s, when cycling was largely dismissed as an activity for people who could not afford to drive. He says: “Now cycling fans are famous for paying £10,000 on a new bike, but when they go into a bike store after that, they are sometimes very measly.” Is it possible that cycling fans are in denial about the realities of following a minority interest sport?

A tough sport to monetise

Around 12 million fans line the route of the Tour de France, one of the biggest sporting events of the year, watching it for absolutely nothing. That's magical in its own way, but a free day out for road race spectators is of little help to promoters of lesser events, struggling to make the numbers add up. Industry sources say that only a handful of other races, including the Giro d’Italia and Paris-Roubaix, run at a profit, thanks to things like lucrative sponsorship deals and sportive entry fees.

For comparison, the average price of a Premier League season ticket varies between £345 at West Ham and £1,073 at Arsenal and matchday receipts account for around a quarter of revenue.

With no income from ticket sales, race organisers need to make money somewhere, and this is where host cities (which we'll come to later) and selling television rights come into play.

It should be noted that the teams who take part in the Grand Tours do not receive a slice of the television rights, but must fund themselves through sponsorship or rich benefactors. The increased subscription costs to watch cycling funnel first to the service provider, then the production team creating the coverage, then the race organiser – none of the extra money a fan will pay will end up in the pockets of a team. Conversely, lower viewing numbers may even impact the appeal of major team sponsorship.

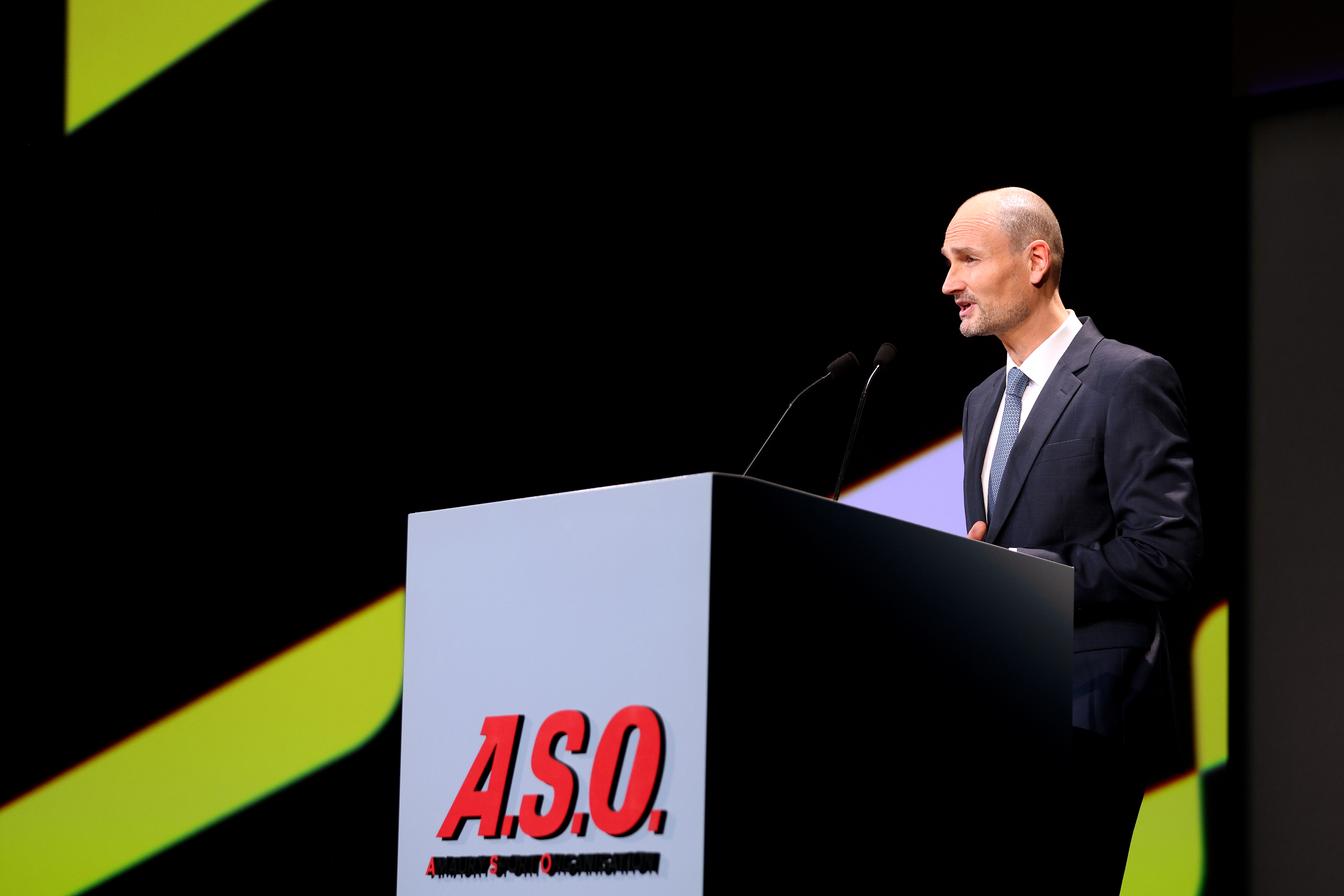

The organiser of the Tour, ASO, does not declare its television revenue, which makes up the largest share of the revenue, but the published figures for cycle racing are modest compared to other sports. A single game in the Premier League generates more in broadcast revenue than the annual media rights earned by the UCI, which administers the UCI World Championships, with Tadej Pogačar the reigning elite men’s world champion and Lotte Kopecky the elite women’s title holder. The UCI declared that it generated £5.1m in income from media rights and distribution before costs in 2023, a sum dwarfed by the £167m received by Manchester City for Premier League rights alone.

ASO will make a lot more money than the UCI from selling the rights to the Tour, which is shown in hundreds of countries worldwide and even just in racing volume, eclipses what the UCI owns. But that is still just one income stream, and not enough to cover the cost of running the event. This is where sponsorship and hosting fees come in.

The Tour was born in 1903 of unabashed commercialism - to boost the flagging sales of the sports newspaper, L’Auto, the predecessor of L’Equipe- and, to put it politely, ASO, in charge since 1965, extract what it can along every twist of the 3,320km course. At its most boisterous, this means the cavalcade of publicity vehicles, which precedes the riders, bearing models of galloping horses and giant plastic smurfs. Showers of free trinkets and samples are hurled into the roadside crowds.

The Amaury family, who own ASO, shares little financial information, but in 2023 it disclosed that it typically received payments of €90,000 from towns hosting the start of a stage, and €130,000 for those hosting a finish. It declines to discuss this further, but the commercial benefits are significant when the travelling circus that accompanies the Tour comes to town. That means the race's route depends on what towns are willing to pay a fee, but in general, there's high demand from local authorities to bring the Tour to town. There are further negotiations on the precise location of the finish line, where there may be tensions between telegenic shots and the safety of the riders.

Some stages are so integral to the appeal of the Tour that negotiations are more complex. Take the ski resort of Alpe d’Huez, which has hosted a stage on 32 occasions and can expect up to one million spectators on its notorious 21 hairpin bends. The finale on the Champs-Élysées has also been woven into the fabric of the nation over the course of half a century: it is understood that ASO has to pay for the hefty costs of policing the event.

The big money for ASO comes from countries prepared to host the Grand Départ, at the start of each Tour, because the hotel and restaurant trade can count on up to a week of bookings. Since 2007, when it departed from London, the race has started more frequently abroad than within France. It launched from Yorkshire in 2014 and will return again to the UK in 2027, with stages in Scotland, England and Wales.

The impact of losing free-to-air cycling

The timing of the announcement that the Tour would return to the UK, just months after learning that free-to-air Tour coverage would end in the country, draws attention to a big question: what is the impact of losing free, accessible coverage of events like the Tour?

It remains to be seen, but there are certainly concerns that higher barriers to viewership might result in smaller audiences for the already fairly niche sport, and less eyeballs could mean less return on investment for sponsors, and eventually less sponsor interest. The next few years in the post-paywall era will show if this has an impact.

What's more, putting a barrier in front of the sport can limit the wider social impact of events like the Tour.

When the Tour visited Yorkshire in 2014, UK Sport contributed £10m towards the event, and the official impact assessment claimed that it attracted 2.3m “unique” spectators along two stages in Yorkshire, apart from the third stage between Cambridge and London. It said the economic impact on the host regions was £128m, with a further £33m for the UK as a whole. [Three years later, in 2017, Boris Johnson, then serving as mayor of London, refused to pay ASO £4.7m to host another Grand Départ because the full organisational cost worked out at £40m].

Though those numbers are about who turned out on the road and in the host towns, the large interest was undoubtedly mainly there because people in the UK could watch the Tour for free in previous years. It was not a niche, paywalled event, and it was something many people have tuned into on a July afternoon over the years. They may not all be hardcore fans, but there's an awareness of the event.

It was therefore awkward that in the midst of ASO's negotiations with the UK government to commit millions of pounds to the 2027 Grand Départ, it emerged that the television rights were being sold to a pay TV channel, very likely putting a huge dent in the public interest in the event.

Christian Prudhomme, director of ASO, made emollient sounds in March about the prospect of an ad hoc agreement for TNT to air the first three stages, starting in Edinburgh and then travelling through England and Wales, to a broader audience. That could involve placing it on WBD's free-to-air channel, Quest – which is showing free highlights of the Giro – or more helpfully, sharing it via one of the three main terrestrial networks, BBC, ITV or Channel 4.

There are precedents for this: for example, Sky Sports shared its coverage of Emma Raducanu’s triumph in the 2021 US Open with Channel 4, and other major sporting finals have been given to free channels in recent years when the national interest and importance are high enough.

The EBU said in a statement to Cyclingnews that ASO had “guaranteed” free-to-air coverage for all three UK-based stages of the men's and women's Tours in 2027.

Moreover, the British authorities have cheerfully promised a similar legacy to that of 2014, “tackling inactivity, improving mental wellbeing, boosting economic growth and supporting communities”- oh and also “to inspire a new generation of cycling fans and riders while boosting cycle tourism right across the country”. But can this be achieved if much of the public won't get to watch the race?

TNT, the EBU and ASO all declined to talk on the record on how they intend to deliver this legacy and cement the impact of the race's visit, but McQuaid points out that everyone involved with cycling in the UK will need to be much more ambitious if the Grand Départ is to enthuse a new generation.

Might new markets in the Middle East and South East Asia come to the rescue, as they have for other sports, including golf, football, and Formula 1, which has added circuits in Qatar and Saudi Arabia? Cycling as a sport has retreated in the USA, but is growing in parts of the Middle East and in Singapore. The Giro d’Italia started in Jerusalem in 2018, but Summer temperatures make it highly unlikely that the Tour could hold a Grand Départ in the Gulf. The emergence of One Cycling - a project backed by the Saudi Arabian SURJ Sports Investment fund - could bring cycling more prominently to the Middle East. With broadcast proposals still unclear, perhaps it could even make it more accessible. However, the future of this project is far from certain despite the enormous capital investment being discussed.

For now, it seems that there is no option but for cycling fans to put their hands in their pockets, which may well mean fewer people watching the sport as many simply can't or won't pay the inflated costs.

As McQuaid puts it: “Cycling sport has a terrible business model unless you own the Tour de France. The sport is luckily populated by people who are so passionate about the sport that it somehow works.”

Nicholas Hellen is a lifelong news journalist who has spent his career at the Sunday Times, where he has served as media editor, news editor, assistant editor and social affairs editor and transport editor.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.