Who is Miguel Indurain?

All you need to know about the first, and to date only, rider to win the Tour de France five times in succession

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

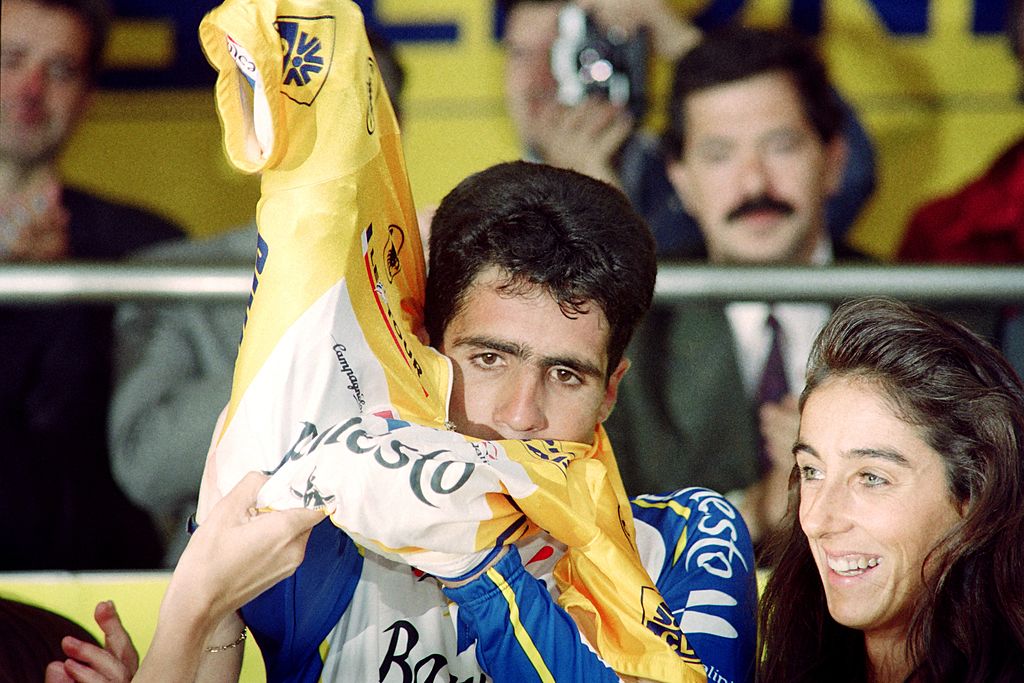

Shy and modest almost to a fault, Spain's greatest-ever athlete Miguel Indurain has never been one to search for a place in the limelight. However, the 60-year-old from Navarra in northeast Spain has an undisputed place in his country and his sport's history.

Indurain is best known for being the model of consistency, being the only ever racer so far to win the Tour de France five times in succession, from 1991 to 1995. Not even Eddy Merckx managed to do that, nor yet - so far - Tadej Pogačar.

Indurain also remains one of just two Spaniards, together with Alberto Contador, to win the Tour more than once, too and he was also, like Contador, the only Spaniard to date ever to conquer the Giro d'Italia, in Indurain's case in 1992 and 1993. (This makes him the only racer in history, too, to do the 'double-double', or win both Giro and Tour in two consecutive years).

The Vuelta a España, however, remained completely beyond his reach, with a second place in 1991 his only podium finish in his home Grand Tour. This dearth of results was partly due to his team opting to prioritize the Tour de France over any other event for Indurain and also partly due to one of his key vulnerabilities: Indurain used to like to say he functioned on solar power and in an era when the Vuelta was held in April, not September, he was certainly much more vulnerable to suffering badly in cold weather.

Then in 1996, his only autumn participation after the Vuelta changed dates the year before and he was obliged by his team to take part, Indurain abruptly drifted out of the back of the bunch and abandoned the Spanish Grand Tour mid-race. Although he then flirted with the idea of switching from his lifelong team, Banesto, to archrivals ONCE, on January 2 1997 Indurain announced he finally opted to retire from racing completely, at the comparatively early age of 32.

Indurain's consistency and calm, cool personality no matter the circumstances and stress levels - it was said he only got angry at the Tour de France three times during his entire career - proved invaluable as a time triallist, his greatest strength as a stage racer. While that skill against the clock also enabled him to conquer such other major titles as Olympic gold in 1996 - his last victory and one of his biggest - the World Time Trial Championships in 1995 and the Hour Record in 1994, undoubtedly the most devastating success he had was in Luxemburg, 1992, in the Tour de France.

Luxemburg, 1992

One of the most jaw-dropping successes against the clock in the history of the race, in the space of 65 kilometres Indurain pushed his own teammate, Armand de las Cuevas, into second place at a massive 3:00. For the rest of his rivals, the distances were even more staggering, with Gianni Bugno the closest, at nearly 4:00 behind. Needless to say, barring accidents or surprises, after Luxemberg's performance - where he was compared, not entirely favourably, as being 'an Extra-Terrestrial' by L'Équipe - Indurain had his second Tour de France firmly in the bag, and not even a spectacular long-distance mountains attack by Italy's Claudio Chiappucci to Sestriere managed to trouble Indurain seriously in the final ten days of the race.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

While Indurain's time trialling was the main foundation stone for all his Grand Tour success, he was a canny operator in other fields and occasionally in the Tour - such as at La Plagne in 1995, Luz Ardiden in 1994 or Val Louron in 1991 - he would deliver a knock-out mountain performance that proved almost equally important towards netting him the final yellow jersey in Paris. Indurain was also a past master at the 'Divide and Rule' strategy, gifting numerous stage wins to smaller teams in order to ensure that when there was a rare, major challenge, to his authority - such at Mende in 1995, thanks to a collective move by the ONCE team - rival squads came rushing to his aid.

Yet by 1996, what seemed like a smooth, almost unstoppable pathway to being the first racer ever to take a sixth Tour abruptly disintegrated. A wet, wild first week of racing left Indurain on the back foot, and at Les Arcs in the Alps, Indurain suddenly was left reeling. Danish race Bjarne Riis delivered hatchet blow after hatchet blow and at Luz Ardiden, the scene of one of Indurain's greatest high mountain triumphs only two years before, the Spaniard gave up all hope of another Tour de France win.

The next day, out of the Pyrenees and through his hometown of Villava, only underlined the scale of his defeat, and a second place in the last time trial of his career at Saint-Emilion at the hands of Jan Ullrich was yet another sign that the writing was on the wall. Five months later, Indurain quit road racing altogether, remaining an occasional commentator for newspapers and television, and doing offroad events like long-distance MTB races.

Having taken up cycling because of the free sandwiches and soft drinks offered to young members of his first club, CC Villaves, after each race, Indurain's build-up to success was a comparatively lengthy one: although he was, until 2023, the youngest ever leader of the Vuelta a España back in 1985, his progress in the Tour de France only picked up after he shed several kilos a few years later and focussed more specifically on his stage racing goals.

Racing as a protege of teammate Pedro Delgado, Banesto's conservative approach with Indurain arguably cost them the 1990 Tour, where they failed to switch leaders when it was clear that Indurain was on the rise and Delgado was cracking. But once Indurain managed to get a clear grip on his best strategy for winning the Tours - essentially, but by no means exclusively, using his time trialling to build an unassailable lead - for five years he was unstoppable.

Born into a conservative, religious family in rural Navarre, it's one of the great paradoxes of Indurain's career that he became the figurehead in 1990s Spain for its modernisation. His time trialling skills were seen as representative of the country's technological, economic and social development into a fully-fledged member of the European Union, and away from the country's more agricultural, backward past. This was helped by his greatest-ever Tour win, in 1992, coinciding with other top international events like the Olympic Games in Barcelona and Universal Expo in Seville. But Indurain himself was never entirely comfortable with such labels and he remained faithful to his rural roots, never moving away from Navarre and staying close to his family home in Villava. Even now, he can be spotted in the area, training on the roads where he forged his pathway to becoming one of the greatest figures of the sport - without ever quite seeming aware that he had done so.

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.