Vuelta a España iconic stages: Loroño, Bahamontes and Spain's bitterest duel

Stage 10, Vuelta a España 1957: Valencia - Tortosa

Even over a half century later, It's still possible to feel a little sorry for Bruno Tognaccini and what happened after he won stage 10 of the Vuelta a España in 1957. The Italian rider had just captured what proved to be the second biggest triumph of his career (the first being a Giro d'Italia stage in 1956). But there was a catch. Nobody - at least in Spain - really cared.

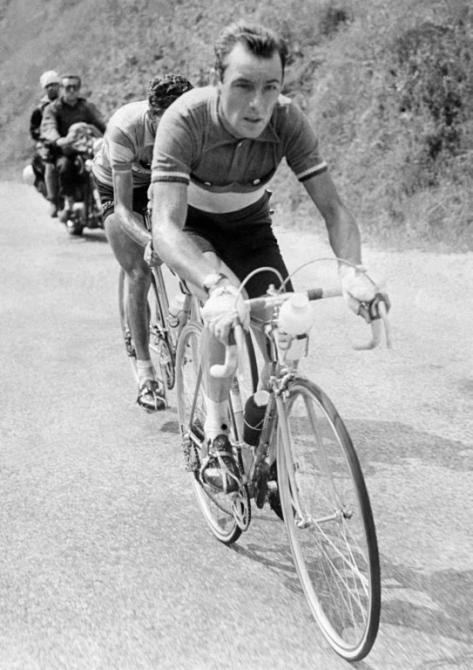

Tognaccini's win, unfortunately, came on the same day that the conflict between Basque rider Jesus Loroño and 1959 Tour de France winner Federico Bahamontes - arguably the bitterest sporting duel Spain has ever known and which divided the country throughout the 1950s - reached its apotheosis. In fact the only story that day that mattered to any newspaper covering the Vuelta was how Loroño had just managed to wrench the lead from Bahamontes in a single stage by gaining 21 minutes on his team-mate. And in the process Loroño had gone from being 15 minutes down on Bahamontes to six minutes ahead - an advantage which Loroño managed to maintain all the way to the finish in Bilbao.

Loroño's spectacular turning of the tables not only wrecked what was Bahamontes' best chance ever of winning the Vuelta: it enabled Loroño to take his only Grand Tour victory in the teeth of Bahamontes' domination of the race and rising popularity. Loroño's greatest triumph came at the expense of ripping down the illusion of team solidarity inside Spain's top squad in the Vuelta and caused a scandal that has become legendary amongst Spanish cycling fans.

Stories about Loroño and Bahamontes' rivalry and how it spread to their fans are numerous - and make later spats between Chris Froome and Bradley Wiggins, say, seem risibly low-key in comparison.

A personal favourite is the time Loroño had apparenty wanted to indicate to 1950s star Charly Gaul - with whom the Basque did not share a common language - over a team dinner one night what he thought of Bahamontes: he picked up a large knife and slammed it into the dining room table. (Bahamontes, sitting on the other side of the same table as Gaul and Loroño, was presumably none too impressed.) Another is that of a diehard Loroño supporter breaking the Spanish coach's fingers and setting fire to the Spanish federation building when he selected Bahamontes, rather than Loroño, for the Tour de France team.

Whether the stories were true or not - and establishing evidence now is all but impossible - barely mattered. What they indicated was while off the bike and out of the public eye the two actually got on fairly well, on the bike and whenever the media were paying attention, their relationship was one of total war. So in the 1957 Vuelta, when Bahamontes was selected by the national coach, Luis Puig, to lead a team packed with Spanish riders who were allies of Loroño, it was a recipe for total anarchy.

The ding-dong battle between Bahamontes and Loroño, the two top Vuelta favourites, began as early as stage one, where Loroño gained a couple of minutes of an advantage. 48 hours later, Bahamontes regained the upper hand with a solo attack in the mountains of Asturias that netted him both a stage win and the leader's jersey.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Loroño tried to strike back with an attack in a snowstorm on stage three to León. And it might have worked, had it not snowed so hard on the Pajares pass that the organisers cancelled the stage: Loroño was so furious that he had to be hauled off his bike.

Bahamontes lost the lead briefly in Madrid, but then another attack en route to Cuenca after forming a working alliance with the French put him back in yellow again. Loroño, meanwhile, was nearly 16 minutes behind yet just as it looked as if Bahamontes would secure his first Grand Tour win, it all went horribly wrong.

The poetic version of how Bahamontes was betrayed is that Bernardo Ruiz - another top Spanish rider fuming because he'd been supplanted by Bahamontes in the 'A' team, and supposedly responsible for engineering Bahamontes' downfall - whispered in Loroño's ear 'Come with me' at the start of stage 10. And although the image is an appealing one, in fact the reality of how it all started was rather more mundane.

Ruiz and two other riders had powered away on the coastroad from Valencia to Tortosa as soon as the starter's flag had dropped, and when they got a 20-second gap, Loroño came across with four others. As 1950s pro Luis Otaño recalls it, there was no doubt that the move was directed against Bahamontes. Otaño recalls Loroño telling him that "During the break Ruiz was yelling 'go, go Jesus, Bahamontes is dropped and you're going to win the Vuelta. You're better than him, fuck it, go, ride!'"

As if that was not clear enough, Bahamontes claims that several of his teammates held onto his shorts (yet another legend that is impossible to prove) when he tried to bridge across in person. In any case, with no support for Bahamontes materialising behind as his teammates revealed their true colours, the stage boiled down to Bahamontes versus eight riders ahead, and the climber had no chance of defending his lead. The only question was how much he would lose it by.

There was certainly no chance of stopping Loroño. Team director Luis Puig, in person, tried to stop Loroño by placing the jeep he was using as a team car across the road. Loroño's response was to ride around the side of the jeep and continue onwards, shouting to Puig as he did so that he would not stop "even if the Civil Guard [Spain's militarized police force] were coming to get me."

On the other hand, the last Bahamontes' group saw of Puig was when the gap was at two minutes and he drove off making signs to them that they shouldn't bother to chase the front group and that he would handle the situation. In fact, he proved woefully incapable of doing so.

Yet more factors contributed to the mystery of the debacle, such as Bahamontes' failure to find any allies at all in the chasing group, even outside his team. Bahamontes has explained this by claiming that Jose Antonio Elola, at the time the Minister of Sport, had sent him a telegram telling him to throw the race in Loroño's favour, an order he could not ignore, bearing in mind that Spain was a military dictatorship at the time. He has, however, never produced the infamous telegram in question, although even if it did exist - and this is where the plot thickens to the point of incomprehensibility - Bahamontes' racing strategy did not make sense.

El Mundo Deportivo's cycling correspondent wrote: "I've been told Bahamontes was under orders not to counter-attack, and I admit it may be true. [But] I can't understand what happened, though, and why a rider who fought so hard to get the jersey in Madrid was so prepared to sit back and let it go out of his reach so calmly."

What makes Bahamontes' explanation about Elola more unconvincing is how hard he fought to get the jersey back after losing it to Loroño. If he had 'thrown' the race, then in a spectacular u-turn the day after Tortosa, Bahamontes attacked on the road to Zaragoza, with Loroño chasing him down. The two slowed down and argued so much that they ignored the fact five other riders, including French contender Jean Mallejac, were in the process of gaining a minute on them by the finish.

Rather in the manner of a boss sending a worker an email even when they are sitting opposite one another, the Spanish Federation then opted for a telegram to tell both Bahamontes and Loroño that they would be kicked off the race if they continued fighting. The two shook hands, said they had settled their differences and Bahamontes promptly tried to quit the race in the middle of the night under his own steam, only for his agent, Evaristo Murtra, to stop him.

And so the war broke out again. As Ruiz later said of the final three days of the Vuelta: "They kept on insulting each other all the time, though. It was incredible. Like something out of a film."

On the stage to Bayonne, Loroño chased down each and every charge off the front by Bahamontes, "who attacked and attacked and attacked," El Mundo Deportivo reported, "turning around to see each time what Loroño could do.

"But Loroño went from strength to strength, hammering on the pedals every which way in order to be totally sure he was gaining the maximum distance possible. When he brought back Bahamontes to 50 metres, Bahamontes sat up, looking at him with a mixture of hatred and admiration.

"Loroño kept on showing his white teeth, as if to show that even if he ran out of physical strength, he'd defend himself by biting."

He did not have to go to such an extreme, though, instead taking his first and only Vuelta in Bilbao in front of an adoring home crowd.

And Tognaccini? His backstory, even now, is worth re-telling. Touchingly, he said after the Vuelta stage that to celebrate his win, he would send one postcard to his wife to let her know and another to Gino Bartali, the Italian star, who had kickstarted his career.

Tognaccini had been a penniless woodcutter in his teens, and he recounted that some of his childhood friends had been laughing at his efforts to save up for a racing bike when, by chance, Bartali was passing by and overheard the conversation between the youngsters. So Bartali wrote out a postcard for Tognaccini, which said simply 'give the bearer of this card one racing bike and send the bill to me, G. Bartali.'

Tognaccini duly got his bike, later went on to have a professional career and even later netted his Vuelta stage, but he didn't forget the man who had made it all possible in the first place. That day in Tortosa, however, his story was completely overshadowed.

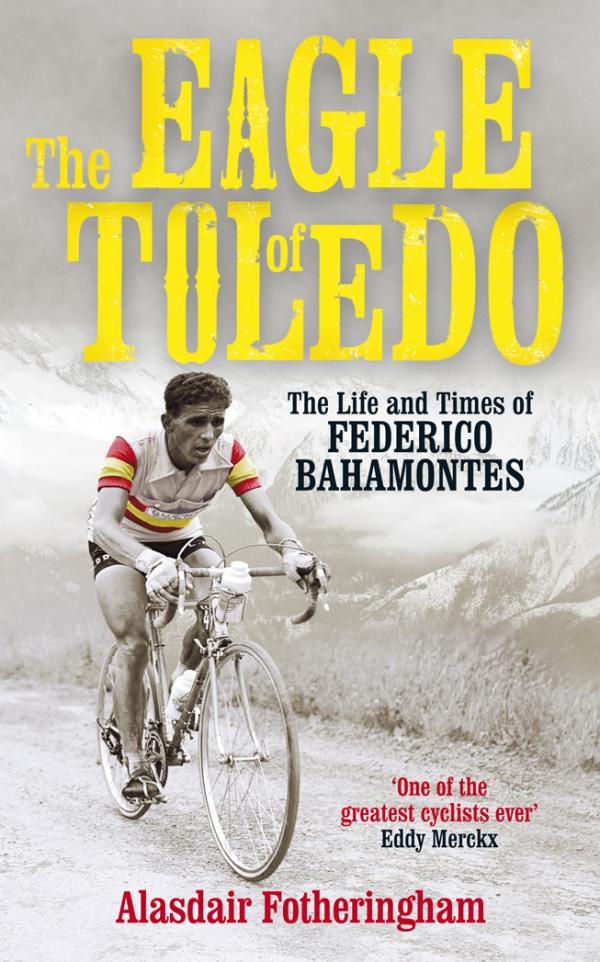

Alasdair Fotheringham is the author of 'The Eagle of Toledo: The Life and Times of Federico Bahamontes.'

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.