Vuelta a Espana 2019: 5 key stages

2 days to go: A closer look at the days that could decide the race

Anything can happen on any given day at the Vuelta a España, making it the most unpredictable and so often most dramatic of the three Grand Tours.

This year, there is ample room for invention on the long road that links the opening team time trial in Torrevieja on Saturday with the concluding procession in Madrid on September 15.

Ahead of the Vuelta, Cyclingnews casts an eye over five stages that might weigh particularly heavily on the final result.

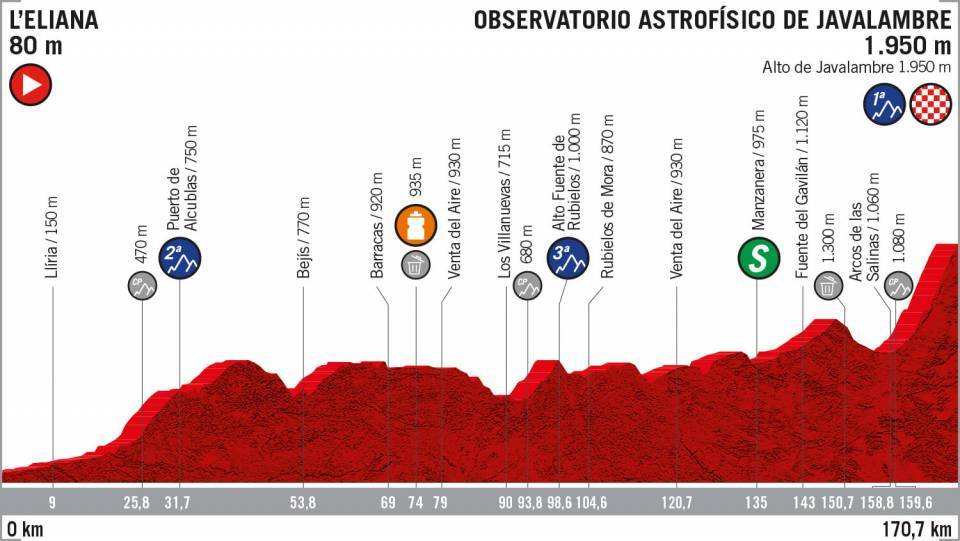

Stage 5: L'Eliana - Observatorio Astrofísico de Javalambre, 170.7km

Unlike the Giro d’Italia or the Tour de France, the Vuelta a España tends to start off with a rather nebulous list of favourites. By this point of the season, riders of lofty reputation and ability can understandably fall prey to deficits of motivation and freshness, allowing room for some rather left-field contenders – and winners – to emerge.

Thus, while the Vuelta organisation has invited a selection of favourites to its 'top rider' press conference on Thursday – for the record: Alejandro Valverde, Richard Carapaz, Nairo Quintana (Movistar), Esteban Chaves (Mitchelton-Scott), Primož Roglič, Steven Kruijswijk (Jumbo-Visma), Miguel Ángel López and Jakob Fuglsang (Astana Pro Team) – there are no guarantees that all of this octet will be competitive across the three weeks of the Vuelta. And that adds an interesting twist to the race.

Wednesday’s first summit finish at the Observatorio Astrofísico de Javalambre is where the fog should begin to dissipate. A mountain stage this early in the Vuelta may well catch out any riders who arrive in Spain still lacking in condition.

Vuelta technical director Fernando Escartin has described this stage as one that “will begin to separate the men from the boys”. The 170.7km leg takes in a winding and rugged route through Aragon, climbing the category 2 Puerto de Acublas and the category 3 Alto Fuente de Rubielos along the way, but the GC men won’t come to the fore until the final category 1 haul to the finish, which has never been tackled before on the Vuelta.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The ascent towards the observatory on the Pico del Buitre is 11.1km in length, though the average gradient of 7.8% is a deceptive one. After a very benign opening section, the gradient gradually ratchets upwards, and flits between 10 and 12% for much of the final five kilometres. There are far tougher mountain stages to come later in the race, but few will reveal quite as much about the contenders as this early test in Aragon.

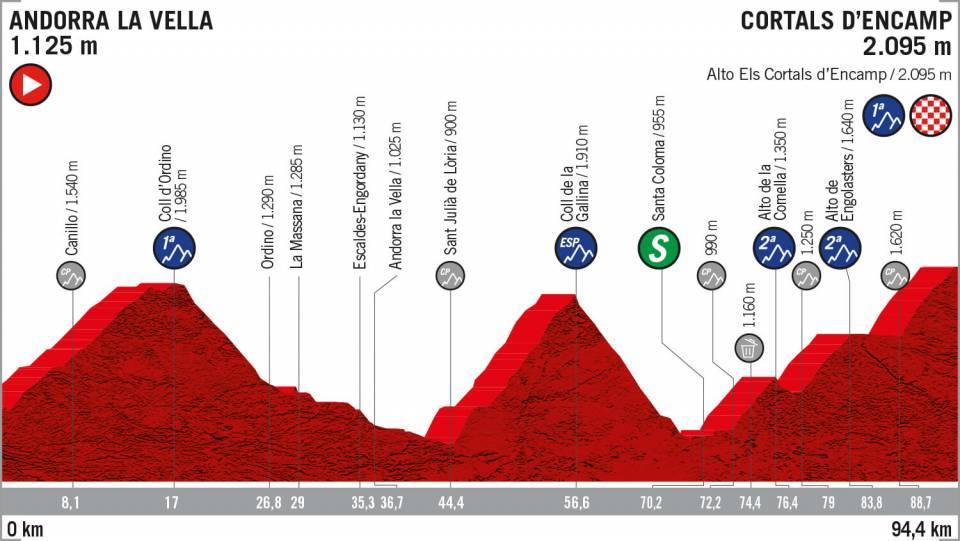

Stage 9: Andorra la Vella - Cortals d'Encamp, 94.4km

The idea has taken hold at the Tour and even on the Giro in recent years, but the modern penchant for short and explosive mountain stages started in earnest on the Vuelta in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The shift from late Spring to early Autumn meant that the Vuelta needed to reinvent itself in order to thrive, and stage distances were shortened accordingly.

In 2000, for instance, when the Vuelta was wedged between the Tour and the Sydney Olympics on the calendar, the race was just 2,904km in length. While the total distance would gradually rise again over the following decade, the abbreviated mountain stage remained a calling card of the Vuelta.

The most dramatic recent example of the genre was the 118km miniature epic to Formigal on the 2016 Vuelta, when Alberto Contador attacked from the gun and Nairo Quintana took full advantage of the ensuing chaos to gain a race-defining 2:40 on Chris Froome. The terrain on stage 9 in Andorra is more obviously difficult than that afternoon in Aragon, which limits the prospect of an ambush, but the brevity of the stage still lends itself to aggression. After all, a slightly longer stage in this part of the world in 2015 was perhaps the second most dramatic day of racing on the Vuelta of this past decade.

There are some five classified climbs shoehorned into just 94.4km of racing during the Vuelta’s short but wickedly tough stay in Andorra. The climbing begins immediately on leaving the start in Andorra La Vella with the category 1 ascent up the Coll d’Ordino (8.9km at 5%). The special category Coll de la Gallina (12.2km at 8.3%) follows before the seemingly interminable three-part haul towards the finish at Cortals d’Encamp, which brings the race above 2,000 metres for the first time.

A short descent links the category Puerto de Comella (4.2km at 8.6%) to the Puerto de Engolasters (4.8km 8.1%), while there is only a brief plateau on which to recover before the finishing, category 1 climb to Cortals d’Encamp (5.7km at 8.3%).

Mikel Landa won here on the Vuelta’s last visit, but as in 2015, the stage winner will not be the only man with a story to tell.

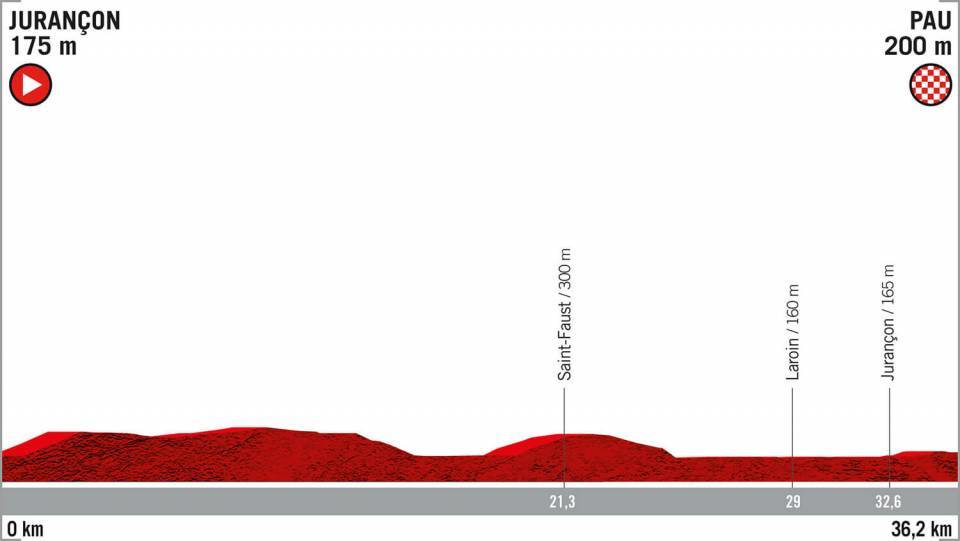

Stage 10, Jurançon - Pau, 36.2km Individual time trial

There may be eight summit finishes dotted around the parcours of this Vuelta, but the pivotal day could come on the rolling roads north of the border in France.

There is just one individual time trial on this year’s route, but its length and its positioning immediately after the first rest day means that it could take on outsized importance in the final outcome of the race.

The route is a technical and rolling one, but those characteristics will hardly deter the man most likely to shine on the road from Jurançon to Pau: Primoz Roglic (Jumbo-Visma). The Slovenian has quickly positioned himself among the world’s best in the discipline and the test comes early enough in the race that accumulated fatigue shouldn’t overly impinge on his performance.

His future teammate Tom Dumoulin built his 2017 Giro d’Italia win around an imperious display in the Montefalco time trial at the same point in the race, and if Roglic is to carry the red jersey to Madrid, he will likely need to produce something similar here – and then manage the second half of the race better than he did on this year’s Giro, where he was gradually diminished by illness.

Pau is hosting a Grand Tour time trial for the second time this summer, and men like Rigoberto Uran and Steven Kruijswijk will expect to match or better their Tour de France displays here. The climbs on the Vuelta parcours are longer and steadier than the punchier fare in July, and the pure climbers will hope simply to limit their losses before the race hits back into Spain and towards friendlier terrain.

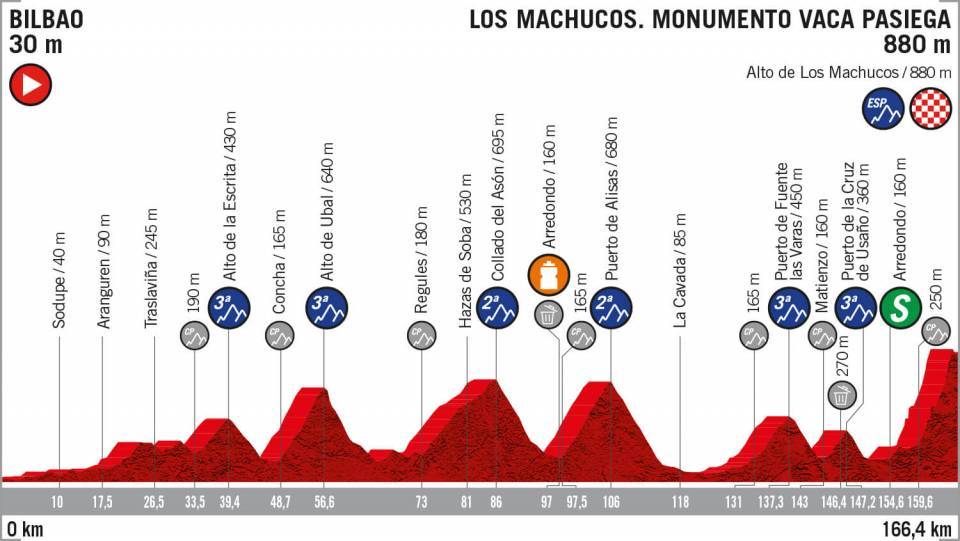

Stage 13, Bilbao - Los Machucos, 166.4km

The Vuelta’s passage through north-western Spain is punctuated by three mountain stages in four days, all of which could prove pivotal in the final reckoning.

Stage 15 brings to the race to the Sanctuario del Acebo, a summit familiar from the Vuelta a Asturias, but approached from a new and demanding side. The following day, the special category finish atop the Alto de la Cubilla provides a most robust test.

It is impossible, however, to overlook the first of this troika, which routes the Vuelta through the Cantabrian mountains ahead of a summit finish on the viciously steep ascent of Los Machucos. The Cantabrian answer to the mighty Angliru first featured on the Vuelta route in 2017, and one imagines that it will become a regular fixture in the years ahead. The since-suspended Stefan Denifl was first to the top on that occasion – the win was later assigned to Alberto Contador – while Chris Froome was distanced by Vincenzo Nibali on its vertiginous slopes.

After a relatively gentle preamble in 2017, Los Machucos this time comes as the seventh climb of an already demanding afternoon, which takes in the Alto de la Escrita (5.9km at 4%), Alto de Ubal (7.9km at 6%). Collado de Asón (13km at 3.9%). Puerto de Alisas (8.5km at 6%). Puerto de Vuenta las Varas (6.3km at 4.5%) and Puerto de la Cruz de Usaño (4.2km at 4.7%).

Los Machucos has its origins as a cattle herding track, and the Vuelta road book denotes the finish line as being near the ‘Monumento al Vaca Pasiega’ meaning the ‘Monument to the Pasiega Cow.’ Indeed, as Alasdair Fotheringham noted in his stage preview two years ago, “there is a metal version of said bovine at the top of the Machucos climb."

Los Machucos is ‘only’ 880 metres high and 6.8km long, but its special category status is nonetheless richly deserved.

The average gradient of 9.2% tells only part of the story, as the road pitches up to a dizzying 25% inside the opening two kilometres. After a short descent, another section at 15% follows, before the gradient drops a couple of percentage points after the midway point. The respite is both relative and temporary – there is another lengthy segment of 25% ramps inside the final 2km, before the road finally and mercifully flattens out on the final approach to the line. The potential for rain in this corner of Spain in September only adds to the difficulty of the stage.

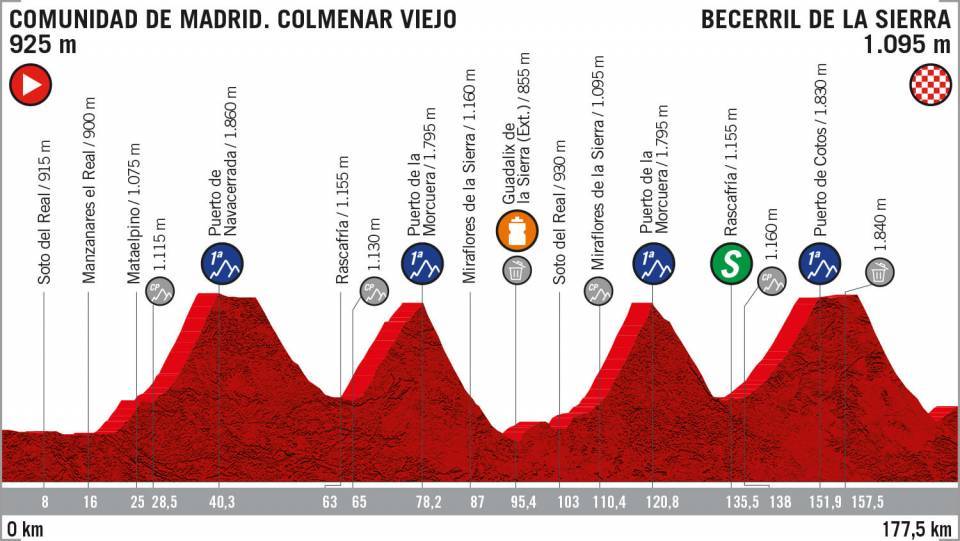

Stage 18, Colmenar Viejo - Becerril de la Sierra, 177.5km

The Sierra de Guadarrama’s proximity to Madrid means that the Vuelta’s forays into these mountains tend to come late in the race and they usually provide compelling drama.

Pedro Delgado snatched the maillot amarillo from Philippa York in controversial circumstances in 1985, for instance, while four years ago, Tom Dumoulin’s surprise Vuelta challenge suddenly ran out of steam on the final weekend, allowing Fabio Aru to ride into Madrid in red. In 1998, a fog-shrouded finish on the Alto de Navacerrada saw the late José Maria Jimenez briefly divest Banesto teammate Abraham Olano of yellow, only to give the jersey back in the final time trial the next day.

These roads, in short, are part of the DNA of the Vuelta. Together with the penultimate stage over the Peña Negra to Plataforma de Gredos, stage 18 to Bererril de la Sierra has the potential to force some rewrites to the race’s script.

The stage features four category 1 ascents, albeit on a rather tortuous route that doubles back on itself, as was the case when the Vuelta came this way in 2015.

The Puerto de Navacerrada (11.8km at 6.3%) is first on the agenda, followed by the Puerto de la Morcuera (13.2km at 5%). After a short loop by way of Soto del Real, the riders then climb back up the Puerto de la Morcuera by way of the road they had just descended for another category 1 ascent (10.4km at 6.7%). The route continues along the road already travelled thereafter by tackling the category 1 Puerto de Cotos (13.9km at 4.8%), otherwise known as the earlier descent of the Navacerrada.

The summit of the Cotos comes 25km from the finish in Becerril de la Sierra, but, if history is any guide, there might be precious little opportunity to recoup the ground lost on the climbs on that drop towards the line.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.