Logistics, money and career sustainability - Why some US riders are saying 'no' to UCI Gravel World Championships

Lauren De Crescenzo explains why riders place priority on Life Time Grand Prix series and races

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Once again, I’ve said 'no' to an invitation to represent Team USA at the UCI Gravel World Championships. Instead, I’m focusing on the final two events of the Life Time Grand Prix (LTGP).

For many US gravel pros, the choice between the UCI Gravel World Championships and the LTGP isn’t just about prestige. It’s a question of logistics, money, and career sustainability.

I weighed in with fellow riders on this subject, as all three women on the US Gravel National Championships podium opted not to accept roster spots for this year's World Championships - three-time US champion Lauren Stephens, silver medalist Sarah Lange, and I, the bronze medalist. Also passing on a spot was Alexis Skarda, who was seventh at the UCI Marathon MTB Worlds.

Skarda, Lange, and I are fighting to stay in the top 10 of this year's LTGP as well, which takes place across the next two weekends. Other riders will wear the red-white-and-blue colours for Team USA for elite and age group categories from October 11-12 in the Netherlands, and the final start lists will be confirmed on October 8.

The calendar

First things first. The timing of UCI Worlds is incredibly inconvenient for LTGP riders. This year's UCI Gravel World Championships were initially planned for Nice, France, on October 18-19, which conflicted with Big Sugar Gravel, the LTGP series finale and mandatory tiebreaker for overall prize money eligibility. Nice pulled out in the spring and was replaced by Zuid-Limburg region of the Netherlands, October 11 and 12. The revised dates, just a week earlier, still conflict with LTGP, now in discord with Little Sugar MTB, which shares the same weekend as UCI Worlds.

It's not just a schedule conflict for many elite riders, but a conflict for earning opportunities. A significant number of pro riders plan to participate in the Little and Big Sugar races, offering $30,000, split evenly among men and women, per race. The top 10 in the LTGP men's and women's competition will share a $200,000 prize purse after Big Sugar.

I won’t be racing Little Sugar MTB this year, but I wondered if it would be wise to fly overseas for the UCI World Champs, then scramble back to Bentonville, Arkansas, and try to prepare for a brand-new Big Sugar Gravel course? That’s not a recipe for success.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Big Sugar is high stakes. The course is entirely different from years past, and I want to ride every inch of the 100 miles ahead of time, and hold, or go better, than my current eighth-place position in the series. I’ll be arriving six days early in Arkansas, traveling from Colorado, not from the Netherlands.

There’s a lot on the line financially, and unlike Worlds, the LTGP is designed to support riders who consistently perform. It’s a much more sustainable model, contributing to the growth, if not the long-term viability, of the sport.

The Worlds course

The UCI Gravel World Championships course doesn’t suit me, or really any of the US gravel racers. The distances are shorter than the LTGP gravel races, and the elevation is minimal:

- Elite Women: 131 km (81.4 mi), 1,190 m (3,904 ft)

- Elite Men: 181 km (112.5 mi), 1,650 m (5,413 ft)

In the US, gravel is defined by long, exposed and mentally grueling courses. At Unbound Gravel 200, the real racing usually doesn’t kick off until at least mile 80 (this year being an exception). By comparison, UCI Worlds feels more like a criterium on bike paths.

When I raced the first edition of Worlds in Veneto, Italy, in 2022, that’s exactly how it felt. Constant twists and paved connectors, I called it “the Bike Path World Champs". Exciting? Yes. But anything resembling gravel as we know it in the US? Not really. That is unfortunate, given that the US is the birthplace of the discipline.

The money (or lack thereof)

The caveat is that UCI Gravel Worlds cost athletes money - flights, ground transportation, food, national kit ($400 per US athlete), and in some cases, accommodations as well. It all adds up fast. Wearing red, white and blue is undoubtedly an honor, but it’s an expensive privilege.

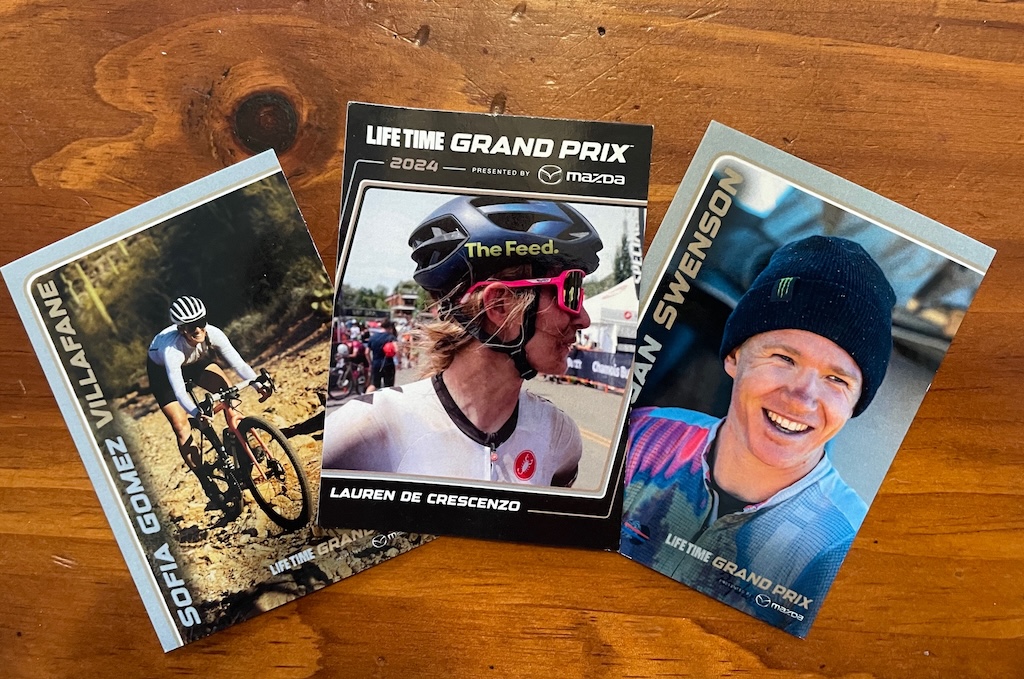

Meanwhile, the LTGP offers financial and career incentives. The series provides a storyline for fans to follow from April to October, and we even get our own trading cards. Sponsors are interested in having riders in the series. We’re competing for a $200,000 series prize purse, split evenly between the top 10 for men and women. This is another thing I love about gravel and the LTGP’s commitment to gender equity, both financially and in terms of visibility.

Ironically, we had a $20,000 prize purse at the 2025 US Gravel National Championships ($40,000 in 2024), split equally among the top 5 men and women (top 7 in 2024). Yet, we had zero funding for American riders to attend the World Championships. Even with the payouts, the funds do not fully cover flights, lodging, mechanics, or any other expenses associated with representing Team USA.

Contrast that with Worlds: a guaranteed financial loss. If you’re not on the podium? Your result barely registers.

Riders weigh in

Fellow US pros Stephens, Lange, and Skarda shared many of the same realities when deciding whether to make the trip to the Netherlands this fall. They weighed the prestige of wearing the national jersey against the financial and logistical strain that comes with racing overseas.

Stephens, a seven-time Road Worlds veteran, told me she’s long understood what to expect from the federation.

“USA Cycling has always been transparent about what expenses fall on the riders,” she said. “They do their best, but full support usually goes to Olympic disciplines.”

When USA Cycling offered funding for the 2023 Gravel World Championships, Stephens said she valued the team experience. But this year, the event is moving from Nice to the Netherlands, so she opted out.

“The change in location, from Nice to the Netherlands, was a big factor,” she said. “I’ve raced there (Netherlands) dozens of times already.”

MTB pro and fellow LTGP competitor Skarda described a similar equation when she lined up for the UCI Marathon MTB World Championships earlier this season.

“It cost about $2,500 for the plane ticket and $400 for the USA kit,” Skarda said. “None of it was covered. If I hadn’t already been in Switzerland for another race, the trip wouldn’t have been feasible.”

Like many privateers, she also pointed out that racing in a national kit offers little return for personal sponsors.

“My clothing sponsors invest in me, but when I wear a national kit, they get no return,” she explained. “That makes it hard for brands to justify supporting Worlds.”

Lange balances an off-road pro cycling career with a full-time job as a dietician with a private practice in New Hampshire. She told Cyclingnews that the opportunity to represent Team USA, earned on September 21, came too late as she had already set her patient schedule for October.

"The gravel national race was the end of September, and then Worlds less than a month away. So travel logistics for me would be pretty tricky. My patient schedule was already set a month in advance. My work, the cost [to travel] and I didn't think the course in the Netherlands was going to be a good one for me. It was a little of all [of these factors]."

These riders framed the decision as one between experience and sustainability. “For experience, Worlds. For my sponsors and my livelihood, the U.S. races,” Skarda said.

Stephens suggested that Gravel might need to explore new funding models.

“In cyclocross, there’s a privately funded project called the Dirt Fund that helps riders get to Worlds,” she said. “Maybe it’s time to consider something similar for gravel.”

Now, these riders are racing where the experience and impact feel most meaningful. Stephens continues to make her own calendar and fund her travel, this time heading to Gravel Burn in South Africa (Oct 25-31).

“I used to be so focused on racing that I didn’t prioritize the experience itself,” Stephens added. “Now I’m looking for new experiences, and this trip will check off my sixth continent of racing.”

The bottom line

While US riders often self-fund their international races, athletes from nations like Italy, Belgium, and the Netherlands receive more substantial backing. The rainbow jersey carries immense cultural weight, and World Champions are celebrated as national heroes.

However, not every federation is flush with resources. Canadian cyclist Magdeleine Vallières, despite her recent world championship title at the UCI Road Championship, financed her own trip to Kigali, Rwanda. Cycling Canada called the situation “complicated”, promising reforms.

Category | UCI Gravel Worlds | LTGP Events |

|---|---|---|

Travel Cost (US Rider) | $4,000–$6,000 (self-funded) | $20–$1,000 (domestic) |

Prize Purse | $0 | $300,000 overall; $25k–$30k per event |

Kit & Sponsors | National kit → little/no sponsor visibility | Own kit → maximum sponsor visibility |

Media Coverage | Global press focused on European podiums | Extensive U.S. coverage all season |

Support Staff | Often none for U.S. riders | Self-organized; simpler logistics |

Financial Outcome | A loss unless on the podium | Top 10 overall payouts; better ROI |

The current UCI World Championship setup requires US elite athletes to sacrifice financially and professionally for very little in return. For many, competing in the World Championships means spending $4,000–$6,000 out of pocket just to be there, while wearing a national kit that offers minimal sponsor visibility and no prize purse. Some athletes accept this as a unique opportunity, and that is fine.

By contrast, the Life Time Grand Prix has become North America’s cultural equivalent of Worlds. The series offers a prize purse, with additional purses at all six events, including Unbound and Big Sugar. Riders race in their own kits, maximize sponsor exposure, and, for domestic riders, travel at a fraction of the cost. More importantly, the LTGP has become a season-long storyline for fans, media, and brands.

While the rainbow jersey carries unmatched historical prestige, the financial reality for US riders tells a different story. So this October, I won’t be lining up in the Netherlands. I’ll be in Bentonville. It's a significant decision to prepare for Big Sugar, which aligns with my professional career goals.

Get unlimited access to all of our coverage of the 2025 UCI Gravel World Championships and the final rounds of the Life Time Grand Prix - including breaking news, interviews and analysis reported by our journalists on the ground in Limburg as the action unfolds. Find out more.

Lauren De Crescenzo is an accomplished gravel racer, having gained fame as the 2021 Unbound Gravel 200 champion and racking up wins at won The MidSouth (three times), The Rad Dirt Fest and podiums at Crusher in the Tushar and Big Sugar Gravel. In 2016, she suffered a nearly fatal, severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) in a professional road race. While the bike almost took her live, she says the bike saved her life as a rehabilitation tool in the following years and she found a new love– gravel and off-road racing. She now wants to be a role model of tenacity, grit, and hard work to promote the vital message of TBI awareness, positively impacting the lives of those affected by TBIs.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.