How hard is the Tour de France?

We look at power, speed, calories, recovery, fuelling, durability, sweat data and more to compare a Tour de France rider's efforts to those of an everyday cyclist

Watching the Tour de France from the comfort of your own home, many of us have questioned if it'd be possible to ride the race ourselves. The world's best cyclists at peak fitness can make it look almost too easy at times, which could lead to a skewed perception of how hard the Tour de France really is.

Deep down, we are all very well aware that the race is light-years away from a Sunday coffee ride with your local cycling club; otherwise, we’d all be lining up at the start. But when you watch the likes of Tadej Pogačar (UAE Team Emirates) powering up an Alp, it’s hard not to feel inspired.

It's a logical step to then wonder how we might compare, and whether we could keep up with the pro peloton, especially on those easy sprint days when the commentators continually remind us they're "taking it easy." Any cyclist who is familiar with power numbers such as watts per kilo, FTP, and so on, will likely have wondered at some point how their numbers would stack up when compared with Wout Van Aert and co.

The questions on our minds often boil down to just one: How hard is the Tour de France?

Spoiler alert: it’s hard. Very hard. Of course it’s hard, it’s the Tour de France, arguably the pinnacle of any pro rider’s career. What we really want to know is 'how hard?'

Over the course of this article, we will try to quantify just that: how hard the pros work during the three-week race and compare that, roughly speaking, with the efforts we mere mortals are capable of.

To provide you with meaningful answers, we dived into race road books from the last few editions of the race, dug through the power files of some of the riders to try and fathom their efforts, along with taking a look at their recovery files to gauge the relative strain that their bodies endure. Then, we gathered data from the general public – ‘normal’ cyclists such as you and I – in an attempt to gain some perspective on the difference.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The terrain

At its close, the riders in the 2021 Tour de France covered 3,414 kilometres (2,121 miles) – not including the riding they did on the two rest days. The 2022 edition of the race was actually ever so slightly shorter with a total of 3,328km (2067 miles) of racing.

Put plainly, if you were to get in a car in New York and head west, that'd get you as far as Salt Lake City. If you were to get onto a plane in London, you could get to Paris and back again five times. If you were in Australia you'd make it from Melbourne right over to Perth on the western coast.

Throughout this distance, riders face a whole host of climbs, from small hills to enormous mountain passes. For the 2023 edition this year, riders will cover 3,404km (2,115 miles) including ascents of the Puy de Dôme and the Grand Colombier in the Pyrenees.

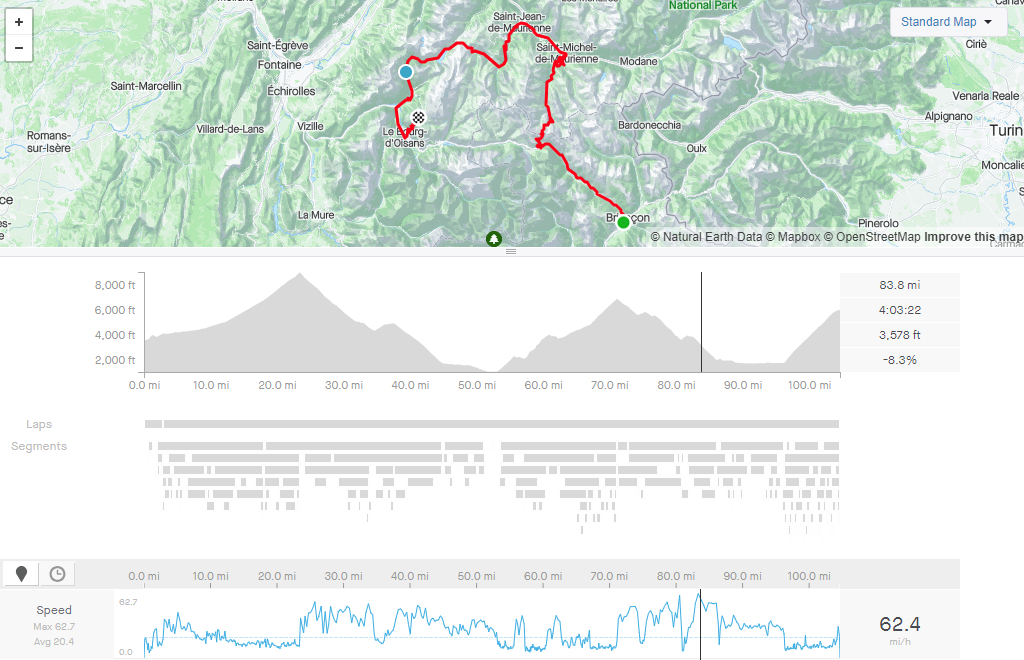

According to data published to Strava by Tour debutant Tom Pidcock (Ineos Grenadiers), in the 17 stages leading up to his impressive Stage 18 victory atop Alpe D'Huez last year, he had ascended a total of 43,110m. That's almost five times the height of Mount Everest.

In addition, while it's easy and obvious to focus on the difficulty of going uphill, there's a level of difficulty involved in coming down the other side too.

For us average Janes and Joes, coming downhill might seem like the easy part – you can often stop pedalling and simply let gravity do the work – but let's not forget these riders are in a race so will be sprinting out of corners and pushing the limits of physics to go as quickly as possible, which in itself takes an enormous amount of mental energy and focus.

As an example of this, according to that same data from Pidock, the maximum speed he hit during Stage 18 of last year's Tour was 62.7mph (100.91km/h). Stage 18 will long be remembered in particular for the jaw-dropping descent of the Col Du Galibier that Pidcock executed on the way to a solo win atop Alpe D'Huez. Although he actually clocked his maximum speed later on in the stage on the descent of the Croix de Fer / Glandon. He also hit a huge maximum cadence of 200rpm during the stage. Descending like this takes a large amount of skill and concentration, it is hard to begin to imagine the amount of focus this requires and the cognitive load it creates.

The training

The Tour de France is ridden by the world's best road cyclists, all of whom are full-time professionals that ride for around 20 to 30 hours per week. But wait, before you quit your nine-to-five job and start cycling all day, know that these riders aren't just riding their bike for fun, they are completing highly tailored structured training programs designed by some of the best physiologists and coaches in the world.

Sadly, even if we did have that expertise at our disposal, most of us still couldn't quit the day job, because professional cyclists are also blessed with the right mix of genetic potential that enables them to respond to such a high training stimulus and recover quickly enough to go again the next day, day after day, week after week.

To try and quantify this, we reached out to TrainerRoad – a popular training-based indoor cycling app turned all-around training platform that boasts a dataset of over a million users – to get a sense of the amount of structured training that the 'average' cyclist tackles.

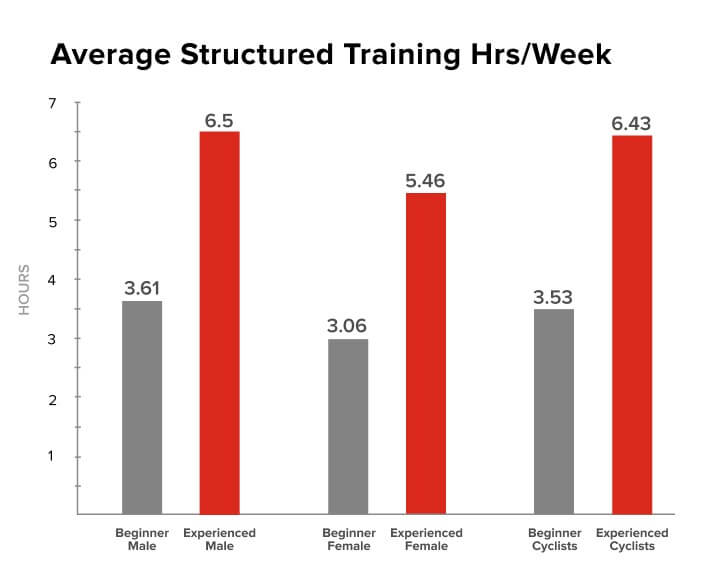

According to TrainerRoad's data, an average 'beginner cyclist' performs 3.53 hours of structured training per week, split at 3.61 hours for men and 3.06 hours for women. While 'experienced cyclists' perform 6.43 hours per week (6.5 hours for men, 5.46 for women).

What this means is that your average beginner is performing just 10% of the training hours of a Tour de France cyclist.

The time cut

To complete the Tour de France, you cannot simply commit to finishing the route, you'll need to do so within the constraints of a time cut on each stage.

According to rule 2.6.032 of the UCI rulebook, exactly what that time cut will be is defined as follows:

"The finishing deadline shall be set in the specific regulations for each race in according with the characteristics of the stage.

“In exceptional cases only, unpredictable and of force majeure [unforeseeable circumstances], the commissaires panel may extend the finishing time limits after consultation with the organisers."

So in layman's terms, the organisers will decide the time cut based on the difficulty of the stage. We won't go into the details of how they then calculate it, but depending on the difficulty of the stage and the pace of the fastest rider, it will usually be the winner's time plus anything between 4% and 18%.

To turn that into an example, if a stage took the winner exactly four hours to complete, the time cut would be anywhere between 9m36s and 43m12s later.

It was a hotly discussed topic last year, with sprinter Fabio Jakobsen fighting on every mountain stage, and in particular on Stage 17, where he pushed himself to the very limit to make the time cut by a mere 15 seconds.

This essentially means that to complete the Tour de France, you need to not only finish the route, you need to be able to do so within a percentage of the winner's time, which leads us nicely onto speed.

The speed

In trying to work out how hard the Tour de France actually is, you will need to know what speed you'll need to be able to ride in order to keep up. The 2022 edition of the Tour was the fastest in the race's history. The average speed of winner Jonas Vingegaard for the 21-stage race set a new record at 42.03km/h (26.12mph)

Combining every edition of the Tour since 2007, the average pace of the winner has been 40.07km/h (24.89mph). Anyone who has ridden a local time trial will know that it's difficult to maintain this pace for 10 miles, let alone the 2000-plus miles covered in the Tour.

However, of course, anyone who's ridden in a group will also know that there's an enormous benefit from being in the draft. That is, of course, until the road points up and gravity does its best to slow you down.

After Ben O'Connor's victory into Tignes on stage 9 of the 2021 Tour, we analysed his performance and saw just how strong the AG2R Citroën rider had to be to win a stage of the Tour de France. The final climb on this stage was Montée de Tignes, which is 31.1km long with an average gradient of 4.1%. This climb took O'Connor 1 hour and 12 minutes, during which he rode at an average speed of 26kph (16.15mph), naturally taking the Strava KOM along the way.

But even if you're not vying for a win, and you're simply trying to make it to the finish line within the time cut, you'll still need to maintain a very high pace. In 2020, Roger Kluge finished at the very bottom of the GC standings, at 6:07:02 behind Tadej Pogačar's winning time of 87:20:13. With that, Kluge still maintained an average speed of 39.09km/h (24.29mph).

The power

A commonly used and widely understood assessment of a rider's ability is FTP, or Functional Threshold Power, which is said to be the maximum amount of power that a rider can sustain for an hour. It is often tested with a sustained 20-minute effort, with the average power from this effort multiplied by 0.95.

Measured in watts, this can be quoted in an absolute figure, or in 'watts per kilogram' where the absolute figure is divided by the rider's weight. So for example, a 75kg rider with an absolute FTP of 300 watts would have a weight-adjusted FTP of 4w/kg.

In our analysis of O'Connor's data, we calculated his absolute FTP to be 395 watts, and according to ProCyclingStats, his weight is 67kg, meaning he boasts an FTP of 5.89w/kg.

Similarly, during the 2020 Tour, we analysed the power file of Tadej Pogačar after his record-breaking ascent of the Col de Peyresourde and calculated his FTP to be 410 watts, or 6.2w/kg.

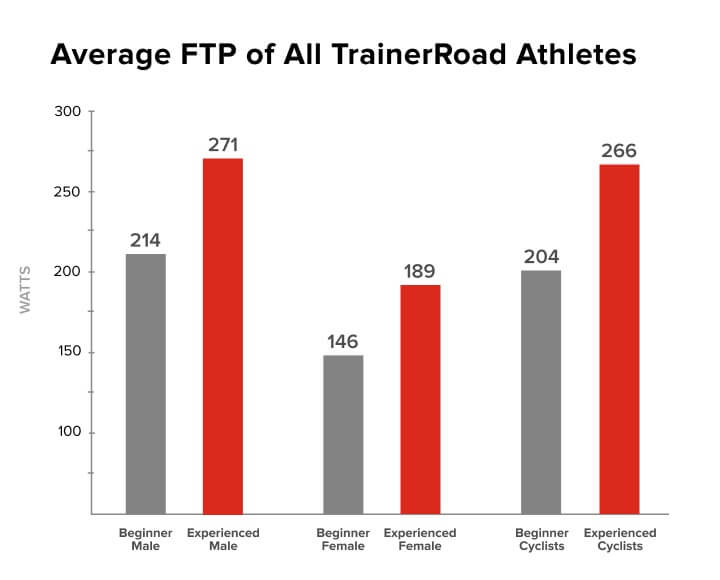

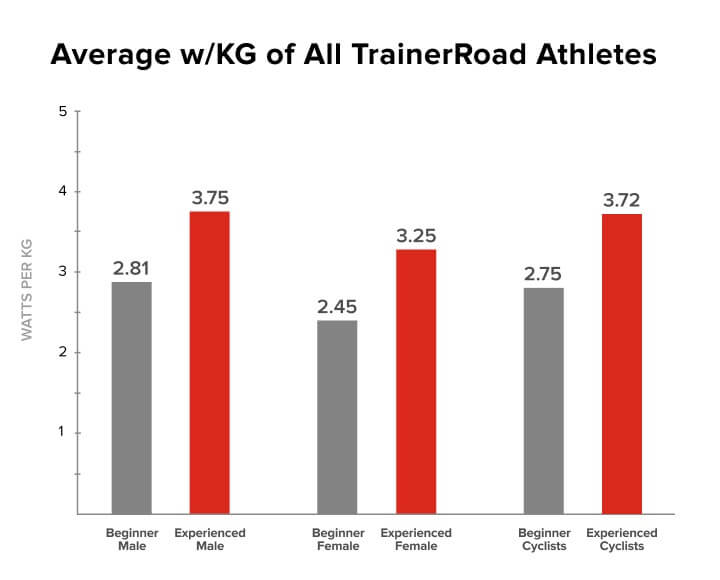

To compare this to an average cyclist, we went back to TrainerRoad, who supplied the average FTP of its entire database.

- Male beginners, the average FTP sits at 214 watts (2.81w/kg)

- Experienced male cyclists, the average jumps to 271 watts (3.75w/kg)

- Female beginners, the average FTP sits at 146 watts (2.45w/kg)

- Experienced female cyclists, the average jumps to 189 watts (3.25w/kg)

- All beginner cyclists combined, the average FTP sits at 204 watts (2.75w/kg)

- All experienced cyclists combined, the average FTP sits at 266 watts (3.72w/kg)

That means Pogacar's 410w FTP is more than 50% better than the average experienced cyclist (266w), and more than double that of the average beginner cyclist (204w).

Of course, beyond this simple metric, there are a lot of other factors at play too. Not least fatigue resistance, which is the ability to output the same high power numbers at the end of a long day or at the end of three weeks of back-to-back racing.

For his ascent of Montée de Tignes in 2021, O'Connor needed to put out an average of 345 watts (5.1w/kg) for the 1h12 duration, on a day where, in total, he averaged 311 watts (4.6w/kg) for over 4.5 hours.

And for Pogačar's ascent of the Col de Peyresourde in 2020, which came on stage 8, he averaged 429 watts (6.7w/kg) for 24h08 at the end of a four-hour stage that included three mountains.

For a reference of just how good this is, anyone who's spent time racing on Zwift may be familiar with the five Zwift Power categories (A+, A, B, C and D). A+ is the highest here, and to get yourself into this category, you'll need an FTP of 4.6 W/kg.

The energy

To maintain all this effort, a rider needs to eat. A lot.

Going back to Tom Pidcock and adding up his calorie expenditure up to stage 18 during last year's race, the Brit had burnt a total of 59,609 calories. That's the equivalent of about 232 McDonald's Big Macs.

So how hard is it for the professional riders?

By now we have a pretty good idea of just how hard the Tour de France is, but these are professional athletes, they're the best road racing cyclists in the world and this is their job. So while it might be an impossible task for us mere mortals to even consider getting round, surely it's just another day at the office for them. Not exactly.

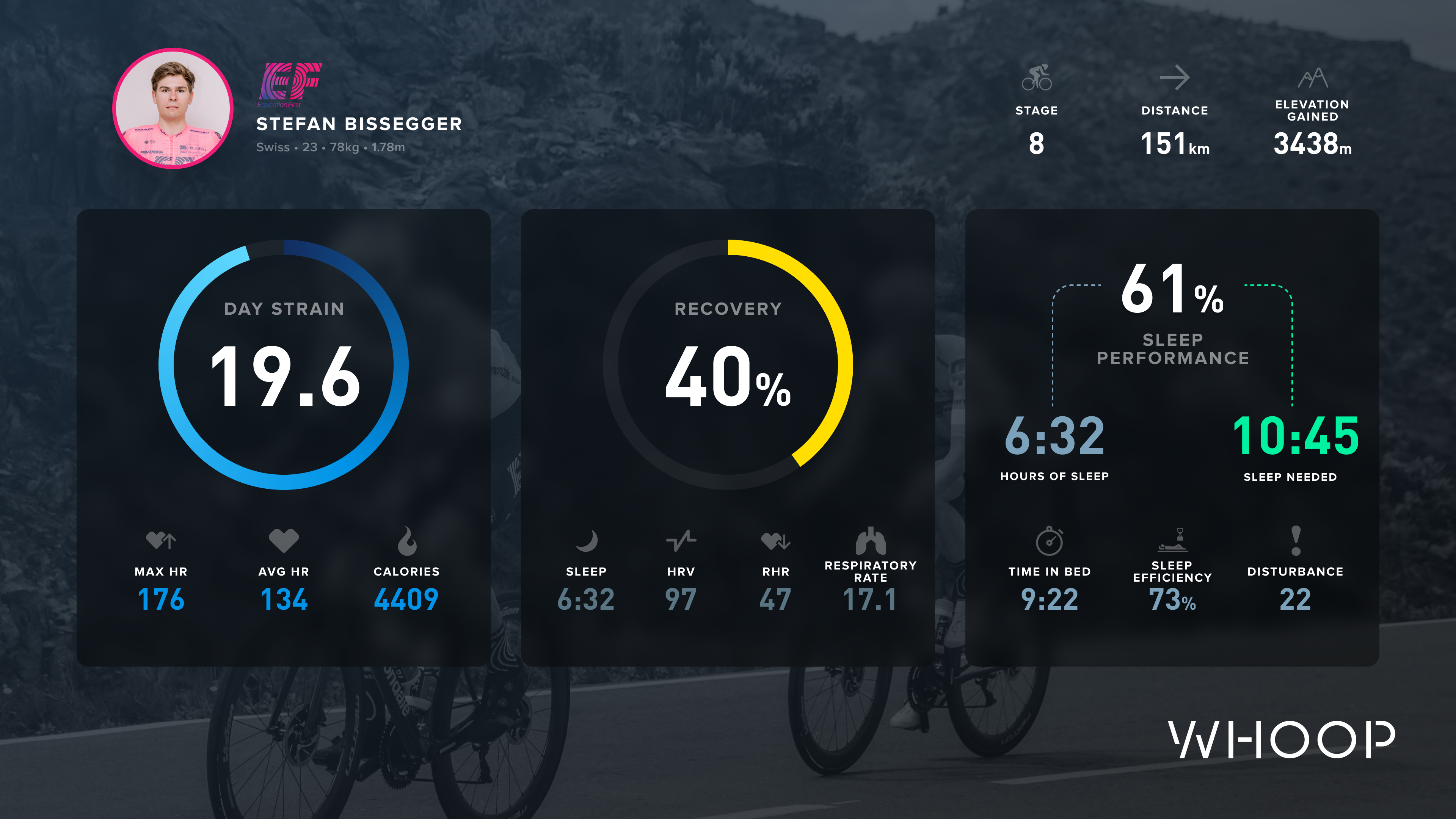

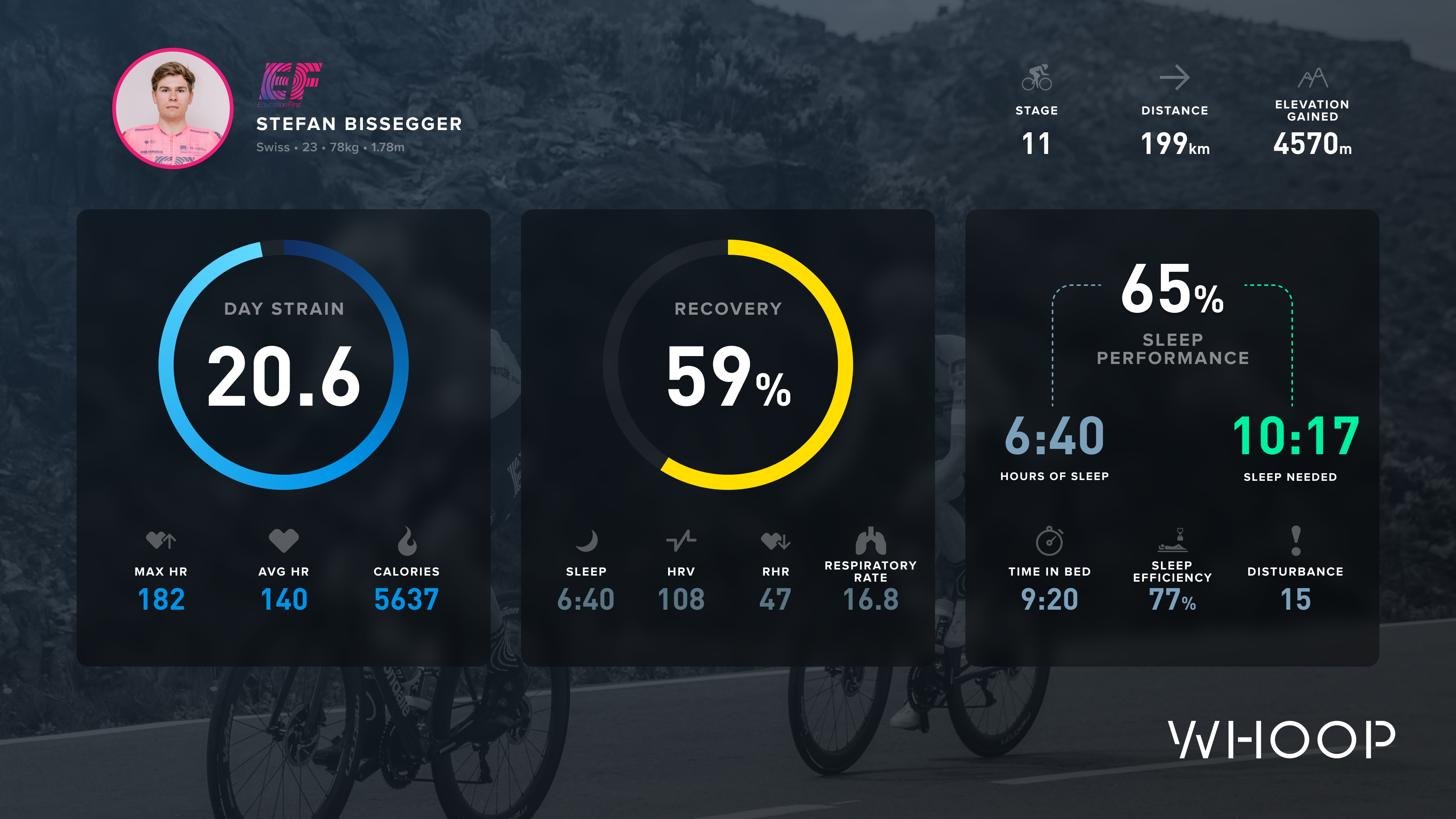

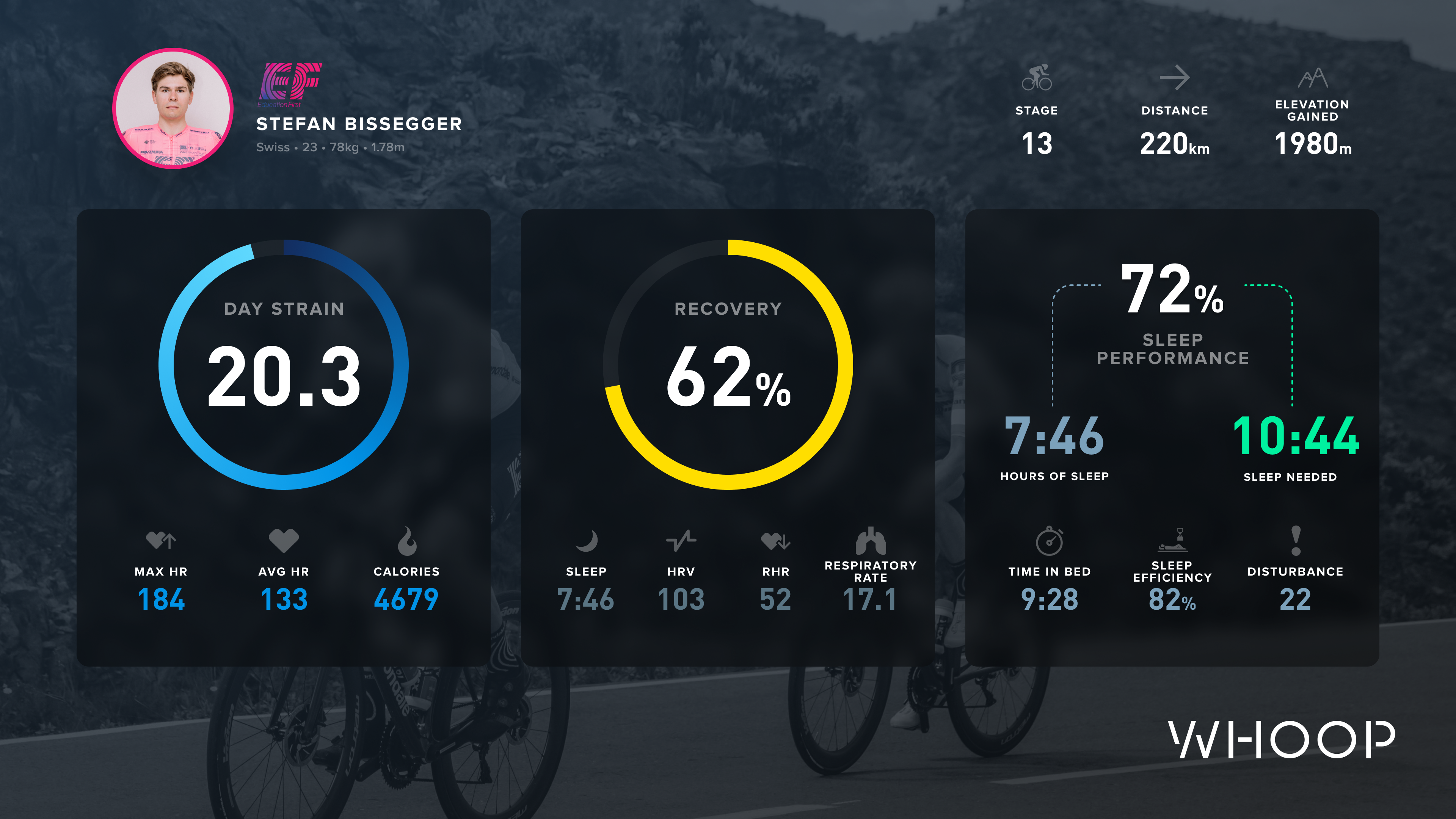

To quantify this, we reached out to Whoop, sponsor to EF Education-EasyPost, and makers of a wearable wrist strap that uses an optical heart rate sensor to continuously monitor heart rate and heart rate variability to quantify various metrics.

For those interested in how this works, Dr Stephanie Shell, a Senior Physiologist specialising in recovery at the Australian Institute of Sport explained the science a little more as part of our Whoop 3.0 review but put simply, it uses these metrics to allocate a 'strain' and 'recovery' score. Both are calculated using proprietary Whoop algorithms, and strain is scored out of 21, while recovery is scored as a percentage out of 100.

Whoop duly shared data for a number of its riders on various stages in the 2021 race. The most complete of these datasets is for time trialling specialist Stefan Bissegger.

Looking at his data, we're able to see how these algorithms rate the difficulty of Bissegger's days in comparison to his own baseline, thus quantifying how hard the days must be for Bissegger himself.

The data here is threefold, covering strain, recovery, and sleep performance data.

Across the nine stages for which we have data, Bissegger didn't have a day with a strain score below 17.4, with all of stages 9 to 13 scoring above 20 out of 21. This suggests that even for him, racing the Tour de France put his body through extreme strain.

Alongside this, his recovery ranged widely. His lowest score was 30%, with his highest being 81%.

Conclusion

All in all, it's safe to conclude that the Tour de France is truly brutal in its difficulty. It's well in excess of the capabilities of the general public and still beyond the reach of experienced, trained cyclists. Even for many of the professional athletes who start the Tour de France, actually finishing it is an altogether different proposal, and each year, dozens of riders miss the time cut.

For those who do make it to Paris, it's still right at the upper limits of their capability and that's what makes it such a thrilling sport for us viewers to consume.

Josh is Associate Editor of Cyclingnews – leading our content on the best bikes, kit and the latest breaking tech stories from the pro peloton. He has been with us since the summer of 2019 and throughout that time he's covered everything from buyer's guides and deals to the latest tech news and reviews.

On the bike, Josh has been riding and racing for over 15 years. He started out racing cross country in his teens back when 26-inch wheels and triple chainsets were still mainstream, but he found favour in road racing in his early 20s, racing at a local and national level for Somerset-based Team Tor 2000. These days he rides indoors for convenience and fitness, and outdoors for fun on road, gravel, 'cross and cross-country bikes, the latter usually with his two dogs in tow.