The high life: The evolution of the pre-Tour de France altitude camp

We join Jumbo-Visma in Sierra Nevada to see what goes into these vital preparation periods

In the increasingly scientific world of professional cycling, the altitude training camp has been a key area of evolution. If you go through the start list for the Tour de France, there won't be many who haven't spent some of the preceding weeks on a lonely mountainside, breathing thin air, turning pedals, and doing not much else.

Cyclingnews has already spoken with Jumbo-Visma’s head of performance Mathieu Heijboer about the benefits of altitude training. But what about the nitty-gritty, day-to-day organisation of a training camp at altitude, and how much has that changed in the last 10 years?

There’s arguably few people as expert on the subject than Jumbo-Visma’s Gerard Spierings. Now in his 50s, the Dutchman began his soigneur career working with Netherlands’ Olympic mountain bike star Bart Brentjens before heading on for a spell with Skil-Shimano in 2010, then Rabobank’s women's team, and now Jumbo-Visma.

Be it phone apps for riders to tell the team cooks exactly what they need for their evening meals, designing a computer program to decide how many recovery drinks a team will consume over four weeks atop a Spanish mountain, or the best kinds of custard fillings for bread rolls, Spierings has the answers.

We sat down with him at Jumbo-Visma's recent training camp at the Sierra Nevada ski station, near Granada in southern Spain. The camp is held at Sierra Nevada’s Centro de Alto Rendimiento (High Performance Centre), or, to give it its Spanish initials, CAR.

Cyclingnews: Compared to 10 or 15 years ago, what are the biggest changes in the way training camps like this one here in Sierra Nevada are run?

Gerard Spierings: Nutrition and training itself. For example, 10 or 15 years ago people go up here to the mountains by themselves, like when Bart and me would go up to St. Moritz for Olympics preparation. There were just the two of us, and most of the time we just did what we thought was best. Here, there is so much more emphasis on training details, right down to intervals of 10 seconds, 12 seconds, 20 seconds, 30 seconds…there’s so much more analysis of lactate levels, nutrition and so on. We’re always experimenting with that, too - what happens if we take 60 grams of carbs, 90 grams, let’s try this, let’s try that. It’s all much more detailed.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The other thing that caught my eye, I noticed the other day Mathieu [Heijboer] was reading a big book called High-Intensity Training. He’s always trying to improve himself, learn new stuff. We do the same for soigneurs with Jumbo-Visma, too; last year we had a Dutch physical therapist in to give us specific training on massage techniques, detecting physical problems and so on. Everybody in our team is trying is improve himself, and that raises the team’s level across the board.

CN: Back in Bart’s day, in terms of the overall program, was it structured around 'sleep high [at altitude] and then train high'?

GS: No, it was 'sleep high, train low', just like now.

CN: For a training camp like Sierra Nevada, how long is the preparation time?

GS: We start thinking about it three months in advance. The first time we actually talked about it was in mid-January, at the first training camp, with the team directors. It was all about how we are going to bring all the material here, do we need the small mini van or a big track, how many people are we going to be sending there, are we going to take extra materials to leave there for the second training camp. And so on and so on.

CN: How many people are here for the training camp here in Sierra Nevada?

GS: Seven riders, two soigneurs, one mechanic, one team director, yesterday we had a visit from our nutritional director, two chefs, because it’s quite a bit of work to prepare three meals a day for seven riders, and all the support staff as well. We’ve rented an apartment, so we prepare all the meals there. It’s got a freezer, a big refrigerator, three bedrooms, so there’s lots of space for seven riders and two chefs. If there’s food left over, we join them. If there’s no food left over, we eat in the CAR restaurant.

CN: What would the riders eat on a typical training day?

GS: Tomorrow, the riders will be doing six hours training, so I’ve spent a lot of today preparing the hypertonic drinks, mineral waters, recovery drinks and so on…I also prepare some food and snacks for the sports director because he’s in the car for six hours, too. We make our own rice cakes, and our own custard mini sandwiches. These are made out of the mini-breads sent to us by a bakery in the Netherlands, we hollow them out and put a little custard inside. They’re low on fibre, high on sugar. Then when the riders come back, the first thing they do is have their afternoon snack, then a massage, then the evening meal. Yesterday, for example, we had meatloaf and rice.

CN: Is this all in your head or down on a piece of paper or...?

GS: We have computer programs. I myself have made a computer program for all the equipment and material we have to bring here in the truck. So I fill in the first page with the number of riders present and how many days they are out at the training camp, and then through some magic trick, everything rolls out: so many bars, so many gels, so many kilograms of recovery powder. Everything rolls out at the push of a button.

CN: Do you have a background in computing?

GS: I’m a mechanical engineer so I know a little bit about computers from that. I went to university in News Brunswick, Canada. Then of course Mathieu Heijboer, our performance director, has his own computer programs in terms of training and recovery.

CN: Is the food here that different to the races?

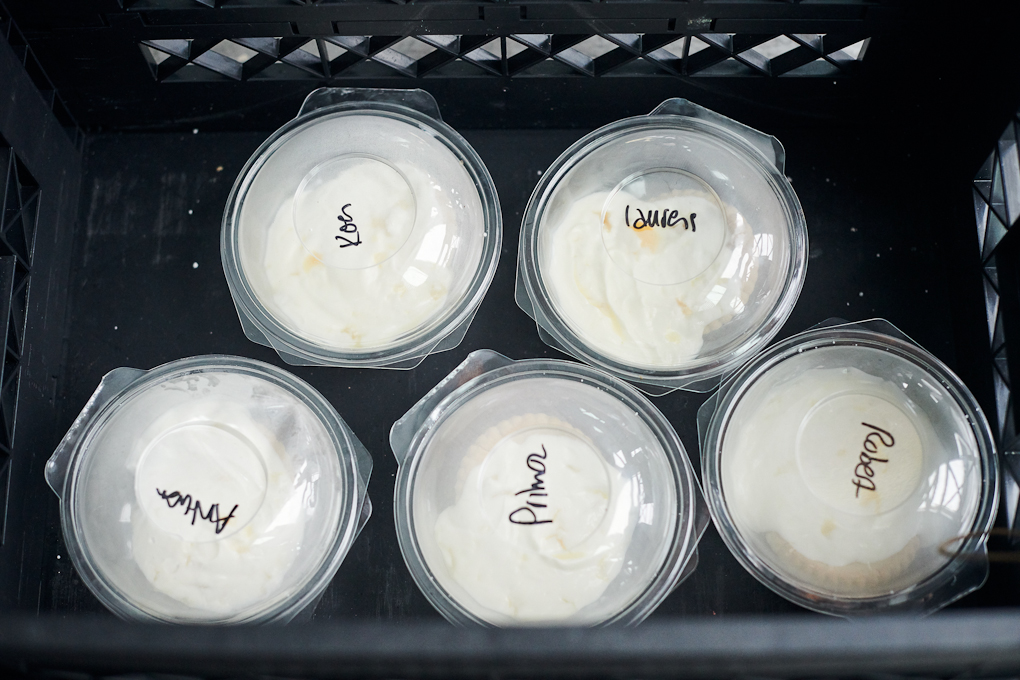

GS: The food is exactly the same. In January 2019, we started with a new food program and a Jumbo food coach came on board. Each rider has a personalised app for the hours, intensity and days that they train and then with another push of the button, everything rolls out in terms of carbs, proteins, fat, what they should eat. We have our own kitchen scales, the chefs measure and weigh how much each rider needs, because they all connected into the same food app as the riders.

For example, Robert [Gesink] inputs in his app. how many hours he’s aiming to train and that app shows how many carbs, proteins, and fat he requires and the chef prepares a meal specifically for him. It’s always a prediction, because if it were done after training there wouldn’t be enough time. Fortunately, the real training doesn’t normally vary so much from that prediction.

CN: What do you do with those diets if rider gets sick?

GS: For example, one of the riders recently had a sore throat. So we gave him three days worth of antibiotics, in collaboration with the team doctors. But the diet doesn’t change. What riders automatically do is that they just drink more than usual when they’re a bit ill.

CN: You say nutrition has changed the most in the last 15 years. Is it also the most complicated area of a training camp?

GS: Yes. Partly because the CAR doesn’t allow us to bring a chef into their own kitchen. That’s why we had to rent an apartment nearby big enough to have the right cooking facilities for a whole month for seven riders. That took some searching by Mathieu. I said it took about three months to prepare for a training camp, but Mathieu always starts his preparation for here almost a year before.

However, a bike is a bike, and for each rider you have a race bike, a TT bike and some spare parts. Organising that part of the training camp is not so tricky.

CN: Have you gone down the Sky/Ineos road of having personalised mattresses for each rider?

GS: Yes. We are sponsored by a Dutch company M Line, and they provide mini-mattresses that go on top of the normal mattresses. They’re the same one used by the Olympic Games squad.

CN: Does every training camp facility have the same policy of not letting the chef into their own kitchen?

GS: No. For example, in Tenerife, we had a chef last year and this year, and they were allowed in the kitchen. And we have another altitude training camp close to Innsbruck in Austria and they’re quite flexible about that, too.

CN: But Sierra Nevada has to have a lot of other advantages to it?

GS: Yes, the CAR has doctors, osteopaths, physios. We have all the training facilities, the sauna - it’s perfect. It’s also little bit higher than in Austria and Tenerife. Here you can ride up as high as 2,600 metres. In Tenerife, only 2, 300 metres. And when we have bad weather here in Sierra Nevada, all we have to do is load everything onto the cars and go downhill and train below the main mountain ranges. Fortunately there’s more variety of roads around here on the drop-offs to the flatter areas, because in Tenerife, there are only two ways up the Teide, from the south or the north. On the Teide, it’s always so busy at ocean level, too. It’s too busy.

CN: Has Jumbo-Visma been anywhere else apart from those three places?

GS: No. I know some riders like to stay in Colorado a little bit. Robert Gesink and a few others often stay on there after the Tour of California, and you get the same advantages as at any training camps. But normally these three places are where we go.

CN: Your performance director seemed very determined that the riders stay up here, don’t sneak off down the mountain for a coffee in Granada, and that they make most of the altitude.

GS: Our riders are professional and they stick with the program. There’s one day off in the training camp, and we do give them a little bit of leeway and they take the team car to go down to Granada. Everybody does need a bit of time out. Plus after a few weeks, you probably need to buy some more toothpaste!

CN: Perhaps the thing that strikes ‘normal’ people the most about altitude training camps is how on earth you can handle the boredom of being stuck in a ski station for weeks on end…

GS: That was what I was thinking - as I’m the only one here for the full four weeks - that I’m going to get bored. But it’s not that bad, there are always things to do: cleaning the truck, doing the laundry, checking we have enough stuff…I go down to Granada and do shopping every three or four days. So I do ‘escape’!

Fortunately I don’t have to do altitude training myself, but I do do some spinning, the other day I went out training and I did a little circuit of 30 kilometres, I did bring my MTB, so I’ve got stuff to do. Of course we have bike racing on TV and we’re watching that every afternoon, as a team. Then personally, I watched the curling World Championships - myself, I’m a bit of a curler.

CN: So if Sierra Nevada has everything, why do you go to Austria or Tenerife?

GS: Well, in April, when we first come here there were 50 centimetres of snow on the ground, and in winter there’s two metres. So it’s just not practical, so that’s why we come in April, a little bit later in the year, and again in May. Then when the ski station closes for the off-season, here it gets much quieter, too - which means, unfortunately, there’s much more time to get bored!

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.