On the road with Philippa York and David Walsh – 'The Escape: The Tour, the Cyclist and Me' book extract

York and Walsh discuss the Tour de France, gender in sport, doping, and much more in wide-ranging new book

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

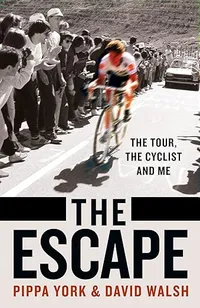

Published by HarperCollins, The Escape: The Tour, the Cyclist and Me by Pippa York and David Walsh is a new memoir from retired cyclist York and sportswriter Walsh, chronicling their time spent following the Tour de France, and reflecting on York's transition from Robert Millar to Philippa York.

In November, the book won the William Hill Sports Book of the Year Award, a prestigious award celebrating excellence in sports writing. Plus, you can buy it at a discount for Black Friday – scroll down for the deal.

The book is told in a mixture of formats, from diary entries written by Walsh during the three Tours he did with York, transcribed dialogue between the pair, and reflective passages from York, recounting her life from childhood to her cycling career.

In this extract, York and Walsh are driving from Hamburg to Belgium as the 2022 Tour de France transfers from Copenhagen back towards France.

It’s early morning when we get out of Hamburg Airport. Ten kilometres later I stop looking in the rearview mirror. Bonnie and Clyde are headed for the Hotel Ibis Dunkerque Centre, a 730-kilometre drive. Well, at least there’s plenty of time to talk.

This is our third Tour together, and days that bring the unexpected don’t upset us anymore. Pippa is imperturbable. Though I’m thoroughly used to her company and at ease with it, I sometimes glance across at my friend in the driver’s seat and think of the man she used to be.

The thing is, these times of sharing so much with her on the Tour have helped me to better appreciate who Robert Millar was. Back in the day he was the best climber in the peloton, and though I was wary of the man, I had huge admiration for the bike rider. Now I realise Robert was much more than that.

I want Pippa to feel the same way about Robert but am not sure she can. And, of course, I’m not one for leaving things unsaid.

David: I’ve asked this before, but surely you must have enjoyed being Robert Millar, the highly successful bike rider? He gave you a life that was good and he helped you to cope with your gender dysphoria. You were so good as Robert Millar, it had to have been compensation for who you couldn’t be? If you were back in your teens, and attitudes were as liberal then as they are now, I’m guessing you wouldn’t want to give up on Robert Millar’s cycling career?

Pippa: No, you’re not right. If Robert Millar had been born in 1998 not 1958, I’d never have been a pro bike rider.

David: Seriously?

Pippa: You’re asking if being Robert Millar, the great cyclist, was some kind of compensation. It wasn’t. Some people who’ll eventually transition go to the heights of masculinity. They think if I join the army, the paras, or whatever, it will knock the femininity out of me. These guys in the army will reprogram me and I’ll be OK. That’s not what happens in professional sport. You step into a world of masculinity and ego, but no one’s trying to force you into manhood.

David: But surely if you’re Robert Millar and you’re so talented, sport gives you fame, recognition, excitement and a decent salary. A lot of people looked up to Millar.

Pippa: But that couldn’t compensate you for something you’re not dealing with. Something you know deep down you should be dealing with.

David: But at the time it helped you to deal with the fallout of not dealing with it?

Pippa: Yes, it helped me to bury it. Because I was so invested in that career, I wasn’t thinking about gender dysphoria every day, every moment. If I throw myself into this cycling thing 100 per cent, I’m not thinking about it.

David: So it worked? Being Robert Millar.

Pippa: Then it hits you, unexpectedly. You see a woman somewhere, and you think, Shit, that could be me. Why isn’t that me? Then I’d have to go back to being Robert Millar, the guy in the bike race.

David: But when you were flying down the Col de Peyresourde in 1983 on your way to winning your first Tour de France stage win, with Pedro Delgado trying to chase you down, that must have been some adrenaline surge?

Pippa: You’re the bike rider at that moment. You’re not thinking about the other thing.

David: But you’re achieving something that very, very few people get to achieve, something you’ve worked incredibly hard for. When you cross the finish line, it must have felt like all the dreams have been realised.

Pippa: I’m aware of that.

David: Are you saying the euphoria of your greatest victories was diminished by internal strife?

Pippa: No, in that moment, it’s not going to arise.

David: When you look back, do you think that while it might not have been an ideal situation, it was a pretty good situation?

Pippa: I do look back and say, 'Yes, wow, that was a good thing.'

David: Does that allow you to look back with affection on Robert Millar?

Pippa: I look at my career and who I was. I was missing one or 2 per cent to be as good a rider as I could be. As a person, much more was missing. Because of gender dysphoria, the whole social side was really stunted. I was emotionally closed to most people. Because I was so demanding and harsh with the bike rider, I was also harsh with people around cycling. In my private life I was closed. I didn’t share things.

David: Maybe it’s the fan in me, but I want to think Robert Millar was a happy person.

From Hamburg we drive south west on the A1, travelling for more than 500 kilometres before crossing the German border into Belgium. There are stops at motorway services: petrol for the car, coffee for the humans. Conversation ebbs and flows.

David: Do you think this is the most content you’ve been in your life? The point of total contentment?

Pippa: Well, David, I do enjoy these trips – and these epic drives are a bonus – and don’t take this the wrong way, but being with you in a car all day every day falls just short of total contentment...

David: All I know is that you’re so much easier to get along with than Robert Millar was.

Pippa: I’ll concede that much, yes.

David: I can tell you have learned to enjoy life.

Pippa: But I wouldn’t want every trans person to think the ultimate reward was driving through France every summer with an over-talkative Irishman and an annoying GPS system. I’m resilient enough to cope with these things, but is everyone?

David: Probably not. But you’ve not answered the question. Has transition made you happier than you ever were before?

Pippa: I feel 95 per cent content. Before, when I was the cyclist, I was about 5 per cent content. I’m speaking about me as a person, not as a cyclist. I’ve got wrinkles now. I wish I was taller, slimmer, whatever. All that stuff. But not having that stuff only takes away a small part of my contentment, like 5 per cent.

David: Ninety-five per cent contentment is about as good as it gets?

Pippa: I’m a totally different person to who I was as a rider. Very, very different.

David: Do you put that down to transition?

Pippa: No, it relates to who you are.

David: Did you ever consider coming back to the Tour as, say, a team directeur sportif?

Pippa: I remember people asking me late in my career if I wanted to do that. I said no, I didn’t. I can remember the specific time I realised I didn’t want to do that. I was in the TVM team, late in my career. At a race in Spain I felt ill. I stopped just before the feed zone, handed my race number to a commissaire and got into the team car. We were behind the race and soon came to a long hill. I could see guys getting dropped, one after the other. I looked at their faces and saw how much suffering they were enduring. The pain in their faces. That’s something you don’t realise when you’re in the thick of a race. Seeing that, I knew I couldn’t do this as a job. I couldn’t drive past those guys and not feel some kind of compassion and not want to help them. These guys looked ten or fifteen years older. I couldn’t drive past them every day. There are other things I could have done in a cycling team, but I didn’t want to be in the car. I just didn’t.

David: When you were suffering in the peloton, and you were very good at suffering, it didn’t bother you that everybody else was suffering. You step back from the sport, start seeing it from the outside and you end up with a completely different perspective.

Pippa: I had conversations with directors that I had ridden with. Talked about the admin side, interacting with sponsors, visiting the bike factory, sorting out equipment. All that I could have learned. The race-day stuff, I didn’t want any of that.

David: I’m pleased that you’re free to be who you always wanted to be, not having to deal with the guilt you once felt when dressing as a girl. That must have made your early life so difficult?

Pippa: Not really, because I buried it that deeply so the wrongness of it didn’t affect me. Since then, I’ve done all kinds of psychological assessments. Now, you can even go on a course to learn self-improvement. Back then it was just the odd book, and what I found is that no matter how hard I pushed the dysphoria to the bottom of the pile, it would still rumble away.

David: Still, 95 per cent content now, that is some climb. You could be the poster person for transitioning!

Pippa: Did you have to stop yourself saying ‘poster boy’ just there, David?

David: You don’t miss much, do you?

The Escape: The Tour, the Cyclist and Me by Pippa York and David Walsh is published by HarperCollins, and is available to buy now.

You can currently buy the book at 33% off – pick it up if you haven't yet.

Philippa York is a long-standing Cyclingnews contributor, providing expert racing analysis. As one of the early British racers to take the plunge and relocate to France with the famed ACBB club in the 1980's, she was the inspiration for a generation of racing cyclists – and cycling fans – from the UK.

The Glaswegian gained a contract with Peugeot in 1980, making her Tour de France debut in 1983 and taking a solo win in Bagnères-de-Luchon in the Pyrenees, the mountain range which would prove a happy hunting ground throughout her Tour career.

The following year's race would prove to be one of her finest seasons, becoming the first rider from the UK to win the polka dot jersey at the Tour, whilst also becoming Britain's highest-ever placed GC finisher with 4th spot.

She finished runner-up at the Vuelta a España in 1985 and 1986, to Pedro Delgado and Álvaro Pino respectively, and at the Giro d'Italia in 1987. Stage race victories include the Volta a Catalunya (1985), Tour of Britain (1989) and Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré (1990). York retired from professional cycling as reigning British champion following the collapse of Le Groupement in 1995.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.