New year, new rules – Here's what the UCI has changed for 2023

From new tech regulations to an overhaul of the ranking system and sweeping changes in women's cycling

The calendar has flicked over from 2022 to 2023, and with that, there are a number of new road racing rules that have taken effect ahead of the start of the road racing season.

There are often only minor adjustments to the UCI's long and dense document of regulations governing the sport, but this year there are more changes than usual that could make a difference at Paris-Roubaix and even the Tour de France.

From a minor tweak of intermediate sprint-based bonus seconds to a complete overhaul of the whole ranking system - not to mention a last-minute U-turn - there are a few things that will look different in 2023.

And then there's the technical element, with a number of interesting new equipment specifications for the new season that affect tall riders like Filippo Ganna.

Here, Cyclingnews looks at all the new rules for 2023 and what impact they may have on the racing.

The UCI's new equipment and tech rules

Handlebar width gets a minimum limit

The aerodynamic equation of Coefficient of drag x Area (CdA) tells us that by reducing a rider's 'A' - their frontal surface area - they will go faster for the same effort, assuming the 'Cd' - the drag of the surface itself - remains equal.

Therefore, take a cyclist and make their position narrower by reducing handlebar width, and you get, theoretically, more speed. Aerodynamically progressive riders such as Jan Willem van Schip, Dan Bigham and Taco van der Hoorn have taken this to extremes in recent years, using track-specific handlebars that measure 32cm at the hoods.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

To combat this being taken into the realm of unsafe, the UCI has introduced a limit on the minimum width (outside to outside) of handlebars to work alongside the current maximum width of 500mm.

The rule now states: "The minimum overall width (outside-outside) of traditional handlebars (road events) and base bars (road and track events) is limited to 350mm." It's worth adding that there is a caveat to the rule for drop bars on track bikes.

The reason for this is not because the UCI wants to spoil riders' pursuit of performance but due to how the steering input is sped up as the leverage is reduced.

Analysis

This shouldn't affect any current riders on the road. The narrowest example we've seen was Van Schip in 2018, whose handlebars measured 32cm at the hoods but flared out to 36cm at the drops. These would be 1cm wider than the limit and, therefore, legal. We can only expect the additional benefit of going narrower than this will be vanishingly small, given that, in most cases, the rider's body will be wider than this.

Therefore, we think this rule is fair. It doesn't negatively affect those who want to take advantage of narrower bars, and it provides a safety net to capture anyone thinking of pushing it further. However, given the ability to create bars with greater degrees of flare or simply angle hoods inward, there will be easy ways for persistent riders to get around this rule.

Adjusted rider reach

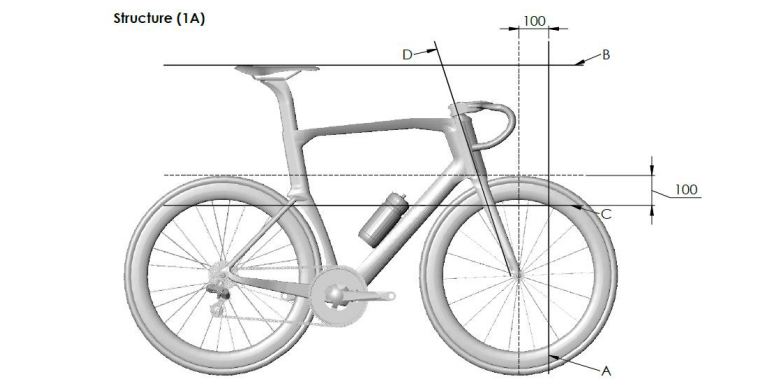

Also pertaining to the position of a rider's hands, the UCI has made an amendment to the rule governing the bike's reach. More specifically, it has doubled the maximum horizontal distance that the handlebar can be positioned in front of the hub from 50mm to 100mm.

Previously this distance was only allowed on track sprint bikes, but it now applies to road bikes too. Whether this decision was made due to the trend toward narrower bars or not, we can't say for sure, but the two will certainly affect each other in practice. Positioning the stem further forward in front of the hub will slow down the steering input somewhat.

It's not uncommon for riders to fit gargantuan stems to their bikes in a bid to get a long, stretched-out position while also offsetting the common practice of sizing down to a lighter, stiffer frame. We've personally seen 170mm stems in use (bikes are typically fitted with stems between 90 and 110mm) but certain niche brands make them up to 200mm in length.

Analysis:

This could open up a wider choice of bike size and spec for riders who like the long, low, stretched-out position, but it would be highly unlikely to see a rider drastically change their position to take advantage of the new rule. More likely is that we see sprinters opting for an even smaller frame to take advantage of the reduced weight, increased stiffness, and lower stack offered while offsetting with even longer stems.

More flexibility for TT extensions reach

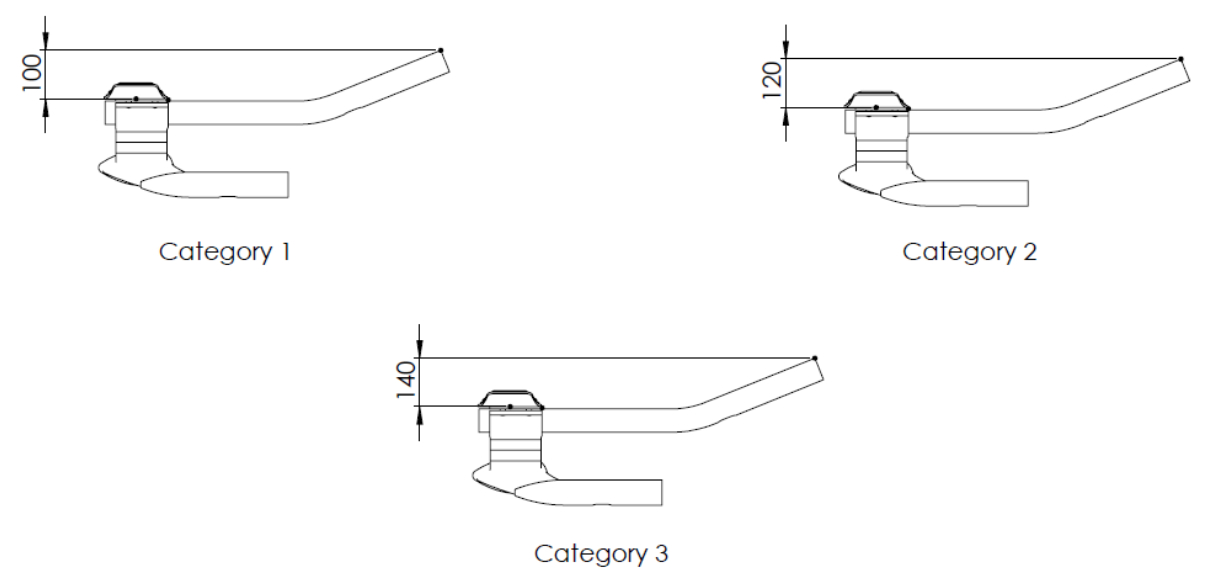

Previously, time trialists were put into two groups based on their height. Anyone above 190cm tall could submit a 'height attestation', which would exempt them from the standard rulebook governing time trial rider position and give them more freedom to find a comfortable and suitable position.

New for 2023, the rules have been changed to a system that essentially replicates the outgoing method, but with three tiers instead of two, with cut-off points at 180cm and 190cm. A height attestation still needs to be submitted for anyone over 180cm.

The new rules state that category one riders (those below 179.9cm) can now have up to 800mm of reach. Category two riders (those between 180cm and 189.9cm) can have a maximum of 830mm of reach, and category three riders are given 850mm of reach.

The new rules also affect the height of the armrest pads, putting a minimum distance between the pads and the tip of the extensions of 180mm.

Analysis

This could, in theory, have a huge effect on which riders are contenders in the time-trialling scene. There's no doubt that bigger riders make better time trialists, but most of today's fastest fall above the 1.9m height bracket.

That's likely because riders who miss the cut-off by a few centimetres are handicapped by trying to squeeze their position into parameters designed around even smaller riders. Mathieu van der Poel at 1.84m, Remi Cavagna at 1.86m, and Rohan Dennis at 1.82m are prime examples of riders who could benefit.

The 3:1 ratio

Previously, components were limited in their dimensions by a ratio of 3:1, meaning that one plane couldn't exceed the size of the opposing plane by more than 300%. For example, if a handlebar was 1cm thick, it couldn't be more than 3cm deep.

However, that rule has now been changed in relation to handlebars and stems, simply limiting the cross-section to a minimum of 10mm and a maximum of 80mm. This means, should a brand so wish, a handlebar can be 1cm thick and 8cm deep.

For one-piece cockpits, the product must now simply fit within a box of parameters that work to the same minimum and maximum limits.

Analysis

This one may take a while to filter into production, but it theoretically de-restricts the boundaries that bike designers and aerodynamicists are forced to work within.

Put simply, this could mean bikes are designed with more aerodynamic handlebars. It could lead to bold design concepts that aim not only to cut through the air quickly in isolation but actively control airflow around the rider behind, not unlike the Ribble Ultra SLR, pictured above.

Helmet dimensions

A trend we saw growing in popularity in 2022 related to the size of the helmet that time trialists wear. The same rules of aerodynamics apply here; however, rather than making the helmet smaller, teams' tech nerds have been making them bigger. This is because helmets are smooth (low coefficient of drag), whereas riders' bodies are less smooth. The bigger the helmet, the more air it can smoothly deflect around the rest of the rider's body. This culminated with a show of weird helmets at the Tour de France opening time trial.

However, in a bid to stop brands from making Spaceballs helmets, the UCI has implemented maximum dimensions for new road and track helmets. Notably, helmets that are already on the market or in production as of January 1, 2023, are exempt.

Analysis

Like the handlebar width rule, this feels like another 'nipping in the bud' of a trend before it becomes anything bigger or a safety issue. There's still nothing to stop a rider from wearing a helmet three sizes too big, so the safety issues might not be completely resolved, but we're happy with any rule that potentially stops cyclists from looking like this.

UCI rankings and relegation changes

Double the scorers

Before we get to the major theme of how the points are divided up, there is one simpler but hugely significant change in that the number of eligible points scorers has doubled.

Previously, a team's total tally comprised the individual tallies of their top 10 riders at that point in time. If the 10th-best point scorer (rider A) was overtaken at some point in the season by the 11th-best (rider B), then the points of rider B would no longer count towards the total.

Now, points are taken from the top 20 riders. That's not quite the whole squad for some WorldTour outfits, who can have up to 30 riders, but it is the minimum roster size for second-division ProTeams.

Analysis

This is something that simply makes sense. In fact, you wonder where on earth the logic for the 10-rider idea came from in the first place.

The old system favoured teams with a select few heavy hitters and disadvantaged those with a more even spread of results through their squads as a whole. Why should those fairly-earned points not count? Most WorldTour teams will still have only two-thirds of their riders represented, but that's only fair since the minimum squad size for possible WorldTour hopefuls from the second-division is 20. It all makes sense now.

Sanity restored to the points scale?

This was the source of so much controversy during the 2022 season, as relegation suddenly became one of the hottest topics in professional cycling. In essence, the sliding scale of points on offer for various finishing positions across the various types and classifications of race was seen as unbalanced and even unfair. There was a heavy weighting towards one-day events, with placings in individual stages - in even the biggest stage races - counting for relatively little. Whether it was Heistse Pijl being worth more than a Tour de France stage or seventh place in the GP du Morhiban being worth more than a stage win in Paris-Nice, everyone had their own example of how skewed the system was.

And so, the UCI has announced sweeping changes to the allocations. Tackling the main issue, results for lower-level one-day races stay the same, but points for individual stages of stage races have been raised significantly. A Tour de France stage win was worth 120 points but is now worth 210 points. Stage wins in the Giro d'Italia and Vuelta a España have similarly risen from 100 points to 180 points, although the prize for first place in all week-long WorldTour stage races stays the same. What's different there - and this also importantly applies to the Grand Tours - is that more finishers now score points. So whereas only the top five used to count in the Grand Tours, now it's the top 15 (with fifth place getting 70 points, as opposed to just five previously). In the week-long races, it's gone from the podium finishers down to the top 10. Lower-level stage races remain largely the same, although minor placings in stages of second-tier ProSeries events have been boosted a little.

As well as individual stages, there is now more of a weighting towards overall finishes in the three Grand Tours, with 1,300 points (previously 1,000) on offer for the Tour de France champion and 1,100 (previously 850) for the Giro and Vuelta winners. There are still 60 points scorers on the final GC, but the points for each placing have all increased. On top of that, the points on offer for the final places in a secondary classification, such as the green or polka-dot jerseys, have now risen (like the individual stages) from 120 to 210 points for victory.

When it comes to one-day races, there are no changes lower down, but the Monument Classics now have their own category. These are the five biggest one-day races: Milan-San Remo, Tour of Flanders, Paris-Roubaix, Liège-Bastogne-Liège, and Il Lombardia. Previously bundled in with other WorldTour events, they now stand alone with 800 points for the winner - up from 500. A more minor change sees Strade Bianche upgraded from the lowest tier of WorldTour event up to the top tier, with 400 points (previously 300) for the winner of that one.

On top of all of that, the UCI has upgraded the value of the Olympic Games and its own World Championships, with 900 points (previously 600) now on offer for the gold medallists. Riders race for their countries in those events, but the positions and points scored still count towards their trade team's tallies.

Analysis

This absolutely had to change. The system was a farce, and the UCI has taken note, implementing a new scale that appears to address all the major flaws. Cycling being cycling, there will never be a perfect system. There are simply too many races, too many overlaps, and too many other complications (geographical, commercial, etc.) to ever create a coherent ranking. With the current structure of the sport (and there's talk of more reforms for 2026), this new system is arguably the best effort.

It will only become clear once the points start rolling in (and there are bound to be new areas of complaint), but on the face of it, this restores some order. It even restores credibility. How do you explain to outsiders why teams are sending their best riders to small races and then trying to place multiple riders in the top 10 rather than win it outright? Rankings do liven things up to a certain extent, but there comes a point when the hunt for points takes away from the true spirit of racing. This won't completely reverse the situation, and teams will still employ some of the tricky tactics they've picked up as the next three-year cycle begins, but here's hoping some balance - and sanity - has been restored.

A U-turn and a reprieve for Israel

Buried in the press release for the new points system was a paragraph announcing another rule change: 'In the event that a UCI ProTeam which lost its UCI WorldTeam status at the end of the 2022 season on the basis of the sporting criterion does not qualify for compulsory invitations according to this table, such a team shall receive compulsory invitations to stage races of the UCI WorldTour, except Grand Tours, in addition to the number of UCI ProTeams provided for herein.'

In plain English, that translates to: 'Israel-Premier Tech will have access to all WorldTour stage races, except Grand Tours.'

Unlike fellow relegation-sufferers Lotto-Dstny, Israel-Premier Tech did not earn the parachute prize of compulsory wildcard invitations to all WorldTour events (effectively wiping out all the negative impacts of relegation). Those invites fall to the two second-division teams who were best-ranked in 2022 alone, and Israel fared so badly that the second of these went to TotalEnergies, although they did grab the consolation of invites to one-day WorldTour races.

Still, the UCI has made a concession that solves a chunk of their calendar-based worries. Given they have already had a Tour de France invite and are likely to get one for the Giro d'Italia, Israel-Premier Tech now have almost no changes in their race programme, despite being relegated. It is, of course, worth pointing out this only applies for 2023, so they will have to rank well to earn more privileges in 2024 and 2025 before looking to rejoin the WorldTour in 2026.

Analysis

This is an embarrassing backtrack from the UCI. Given Israel-Premier Tech boss Sylvan Adams was threatening to take the governing body to court over relegation, it looks very much like an appeasement measure. It's clearly a bespoke let-off loophole, rather than a general new rule, as its wording specifies the 2022 season, meaning it can't be in force in the future. Lotto-Dstny were already cushioned by existing rules, and this step means the consequences of relegation - portrayed as so doom-laden - will hardly be felt in 2023. The UCI trades some credibility for the placation of a fiery team boss and important stakeholder.

Women's

There have been sweeping changes to the Women's WorldTour in 2023, which we have covered in a separate in-depth feature. Leaving aside the more structural changes, we've picked out a couple of the new racing rules here. For the full feature, hit the link below.

Development a key focus in sweeping changes to 2023 Women's WorldTour

More cars on the road

The UCI will now allow women’s teams to have two team vehicles during events that are six days or longer on the Women’s WorldTour.

Prior to this rule, and for all other events on the international calendar, women’s teams have only been permitted to have one vehicle in the race caravan to support their riders. A second car per team will now be allowed - except in circuit races and on final circuits - at some of the calendar’s biggest races, including the Tour de France Femmes, Giro d’Italia Donne, La Vuelta Femenina, Tour of Scandinavia, Simac Ladies Tour, and the Women’s Tour in 2023.

Analysis

A second team car will be a welcomed change for teams and sports directors at the sport’s top level. It will allow a team to support their riders in the breakaway, riders in pursuit of special jersey classifications and riders who experience mechanicals without facing the dilemma of having to choose to support one over the other.

Allowing teams to have a second support vehicle also reduces the number of times a team car passes the peloton, between the peloton and a breakaway, therefore improving overall peloton safety.

Bigger pelotons at bigger races

The number of riders starting per team at certain stages races is about the change. Article 2.2.003 is the new rule that now stipulates, for stage races of six stages and more of the UCI Women’s WorldTour, the number of starting riders per team has increased to seven.

This rule will apply at the Tour de France Femmes, Giro d’Italia Donne, La Vuelta Femenina, Tour of Scandinavia, Simac Ladies Tour, and the Women’s Tour in 2023.

The opportunity to field one rider extra can significantly impact race tactics and give teams more options during the longer races throughout the season.

Analysis

Adding a seventh rider to each roster for the longer stage races on the Women’s WorldTour is another step in growing the foundation and broader base of the Women’s WorldTour. It could increase a team’s competitiveness within a race by heightening the degree to which a team can support the pursuit of both stages and special classifications. It will also allow a team to continue with tactical numbers even in the unfortunate case of early abandons due to crashes and illness.

Some WorldTeams and Continental teams might struggle to meet the new requirement. The sport’s growth is undeniable with an increasing number of race days on the Women’s WorldTour, and although top-tier teams are now permitted to hire 20 riders, the rosters remain at just 13-16.

Miscellaneous

TT support cars, stay back

One of Cyclingnews' top stories in March last year concerned the rather odd theme of bikes on top of cars. Not an unusual sight, granted, but a bit of aero trickery that, even if it amounted to the most marginal of gains, the UCI has now looked to clamp down on.

What happened was that teams discovered that, in a time trial, the team car following a rider can offer an aerodynamic advantage, and that stacking the car full of bikes can enhance this. We all know the benefits of riding with a large object in front of you but you also get a small benefit from having one behind, given some pretty complicated physics that basically means the car pushes air forward.

That's why we saw the likes of Filippo Ganna and Jonas Vingegaard being trailed by stacked team cars when they could never feasibly need - or even possess - that number of spares. Debate was sparked and TT expert Alex Dowsett spoke of a 'grey area' that went against the spirit of fair play.

The UCI eventually took the same opinion and has now increased the minimum permitted distance between TT rider and car from 10 to 25 metres. Interestingly, this was initially supposed to be 15 metres before the rule was revised before final publication. Teams are still allowed to put as many bikes on their cars as they like but there's arguably no point anymore.

Analysis

This is not something that will change the face of the sport in any way, but it will put an end to a mildly controversial practice. Even with the old rules, the gains were as marginal as they come. A Belgian professor calculated that a standard car following at 10 metres would amount to a 0.23% reduction in drag coefficient, translating to 0.078 seconds per kilometre or 3.9 seconds over 50km. That's without the stack of bikes, which would have a smaller impact still. Bikes can remain on roofs, but more than doubling the distance effectively kills the gain and kills the debate.

Any gear goes for juniors

For years, junior riders have been restricted in the gears they are permitted to use, but now they're free.

Firstly, the jargon. Junior racing used to have a maximum authorised gearing, which was whatever gave a distance of 7.93 metres per pedal revolution. That most commonly equated to a gear ratio of 52/14 - 52 teeth on the big front chainring and 14 teeth on the smallest cog on the rear cassette.

The main argument for limiting the gearing was to protect the muscles and joints of young, growing riders. However, the UCI has now indicated that medical evidence no longer supports this theory. On top of that, gears in these sizes are increasingly rare, making it a logistical headache to even get these specific components onto bikes.

So as of now, the rule has been crossed out and juniors can use whatever gears they please.

Analysis

The theory that bigger gears were harmful to younger riders had already been debated, but it has looked increasingly silly in recent years amid the youth revolution that has swept the sport.

The youth ranks have become increasingly professionalised, which is why riders are turning pro - and winning - younger than ever. Some are even going straight from the juniors into the WorldTour, which shows that the gap between the ranks are smaller than ever. In that respect, gearing restrictions seem outdated. With the added supply chain issues, it's a rule no one will miss.

More bonus seconds

A small one, but even the biggest GC riders have shown that bonus seconds are worth fighting for.

Until now, intermediate sprints have carried bonus seconds for the top three, with three seconds for the first across the line, two seconds for second, and one second for third. The new rule allows race organisers to double that tally, but only if there is just one intermediate sprint on the stage in question. In that case, they are free to raise the bonus seconds to 6-4-2 for the top three.

Analysis

Bonus seconds have generated a surprising amount of interest among GC contenders and this rule allows for the stakes to be raised a little more. However, it's unlikely it will come into force that often, given many major races - who sell sponsorship on the back these sprints - will stick to two or even sometimes three.

Besides, the rule doesn't seem to have much value in the first place. The Tour de France used to offer its 'Point Bonus' mid-stage sprints and, after scrapping them and using just one intermediate sprint per stage in 2022, is reportedly bringing them back in 2023. They're worth eight points for first place, which is nowhere in the UCI's regulations.

Kirsten Frattini is the Deputy Editor of Cyclingnews, overseeing the global racing content plan.

Kirsten has a background in Kinesiology and Health Science. She has been involved in cycling from the community and grassroots level to professional cycling's biggest races, reporting on the WorldTour, Spring Classics, Tours de France, World Championships and Olympic Games.

She began her sports journalism career with Cyclingnews as a North American Correspondent in 2006. In 2018, Kirsten became Women's Editor – overseeing the content strategy, race coverage and growth of women's professional cycling – before becoming Deputy Editor in 2023.