Giro d'Italia: Five key stages from the 2022 race route

Blockhaus, Mortirolo, Santa Cristina and Dolomite tappone draw the eye in route light on time trials

Rather than the traditional big reveal in Milan, the route of the 2022 Giro d’Italia was doled out in installments by press release over the course of the week, seemingly a side-effect of RCS Sport’s ongoing negotiations over domestic television rights for next year. Yet if the manner of delivery was rather underwhelming, the end product was as intriguing as ever.

At first glance, a striking feature of the 2022 Giro d'Italia is the relative brevity of many of its stages, with the longest coming in at 201km. Notable, too, is the paucity of consecutive mountain stages, not to mention the meagre ration of time trialling, with just over 26km on the route, the lowest amount since 1962.

The route is still populated with mighty mountain passes, and old favourites abound, from Etna and the Blockhaus down south to the Mortirolo, Pordoi and Fedaia in the final week. Yet there is a degree of innovation on show too, particularly in a second week where medium mountains dominate, and where the route lends itself to a degree of invention from those willing to test the waters in places beyond the set-piece GC stages. To distill the Giro’s three weeks down to just five key stages is to sell the race short, but, as ever, some days simply leap off the map.

Stage 9: Isernia – Blockhaus, 187km (May 15)

The early summit finish at Mount Etna on stage 4 and a deceptively difficult run through the mountains of Calabria and Basilicata on the road to Potenza should sketch out some early contours to the general classification, but the summit finish atop the Blockhaus ought to be the defining moment of the Giro’s opening week.

The Blockhaus – its Germanic name is a residue of Habsburg influence in the area – first featured in 1967, when a young Eddy Merckx was the stage winner, and its place in Giro lore was cemented five years later when the Belgian faced one of the rare crises of his imperial phase as he was distanced by José Manuel Fuente on a split stage just 48km in length.

Mauro Vegni may have opted for shorter distances on this Giro – the longest stage is only 201km – but there is nothing diluted about this demanding stage through the Apennines of Abruzzo, which racks up just shy of 5,000m of climbing across its 187km. On leaving Isernia, the first classified ascent is the category 2 haul towards Roccaraso before an undulating run through the province of Chieti on terrain familiar from Tirreno-Adriatico.

The day’s true difficulties come in the final 50km, however, as the race reaches the Maiella National Park, with the category 1 Passo Lanciano followed by the summit finish on the Blockhaus, which returns after a four-year absence. Nairo Quintana danced into the maglia rosa on that occasion, when the Giro tackled the Blockhaus – also on stage 9 – by its longest and steepest approach for the first time. That 13.6km ascent again features in 2022, with an average gradient of 8.4% and sections of 14% with a shade over 5km remaining.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

“It's the hardest of the three roads up to the Blockhaus, because it's steeper and longer than the others,” local resident Dario Cataldo told Cyclingnews in 2017. “The first part, the lead-in, is very similar to Etna in that it's regular, but the last 12 or 13 kilometres are really hard. Up there, being on the wheels won't count for anything and having a team around you won't count for much. The legs will make the difference.”

In 2017, that novel ascent of the Blockhaus was the day’s only classified climb, but it still produced significant gaps – not to mention high drama, when the challenges of Geraint Thomas, Mikel Landa and Adam Yates were ruined by a crash at the foot of the ascent. It also provided a reliable indicator of the form lines on that Giro: Quintana won the day, but, on hostile terrain, Tom Dumoulin limited his losses to just 24 seconds. Expect the Blockhaus to deliver similar portents this time out ahead of the Giro’s second rest day.

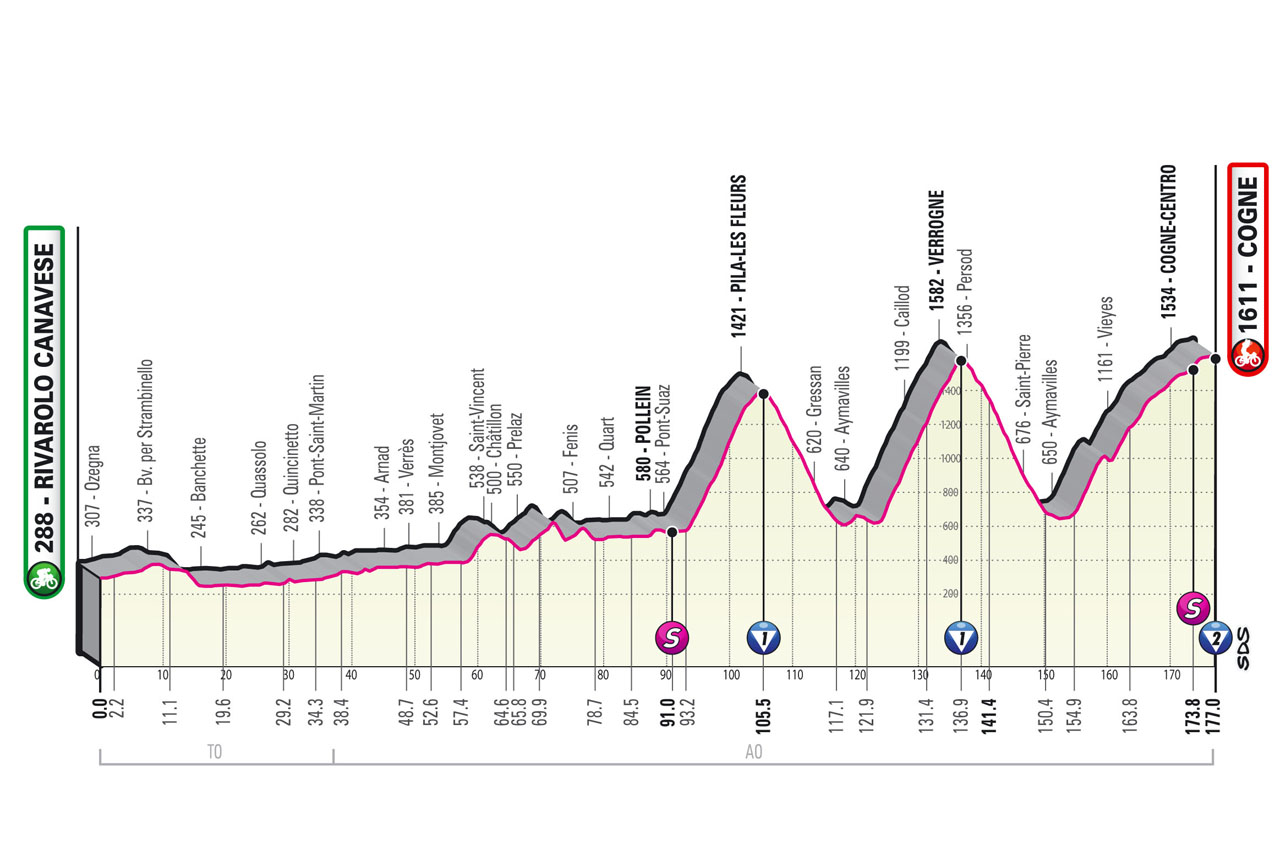

Stage 15: Rivarolo Canavese – Cogne, 177km (May 22)

The Giro follows a distinct pattern as it winds its way northwards in the second week, alternating between hilly and flat stages, but the next obvious set-piece for the GC contenders comes on the eve of the third and final rest day, when the race enters the Alps. That said, the second week should not be dismissed, given that the lack of high mountains is offset by the scope for invention offered by the finales in Jesi, Genoa and, above all, Turin.

Indeed, it would be tempting to list stage 14, with an intriguing circuit over the Maddelena and Superga that packs some 3,470m of climbing into just 153km, among the five key stages of this Giro. Too short for an early break to ease clear and too unrelenting for any one team to control affairs, this nervous stage has the potential to make a significant impact on the GC picture. That said, the following day’s foray into the Alps looks certain to do so.

It’s a stage of two distinct parts, starting with a gentle run along the Dora Baltea river as the race heads out of Piedmont and towards Valle d’Aosta. The climbing begins shortly after the midpoint, with the category 1 ascent towards Pila – which featured as a summit finish in 1987 – though only as far as Les Fleurs, at an altitude of 1,421m.

Another long, category 1 climb follows shortly afterwards, as the gruppo tackles the almost 20km haul up to Verrogne, which was included on the pivotal stage to Courmayeur in 2019. In this part of the Alps, passes tend to be long and steady rather than short and steep, and the finale of this stage will be a test of staying power rather than of explosiveness, given that 46km of the final 80km are uphill.

The final ascent to Cogne is itself some 22.4km in length, and though the average gradient is a mild 4.3%, there are several demanding stretches in the opening third of the climb from Aymavilles, and the road still drags inexorably upwards in the Gran Paradiso National Park in the final 10km. Any contenders carrying the weight of a combative second week in their legs could endure a setback here.

Cogne itself has never previously hosted a Giro finish, but the race has been this way before. In 1985, Andy Hampsten marked his Giro debut with a stage victory in nearby Valnontey.

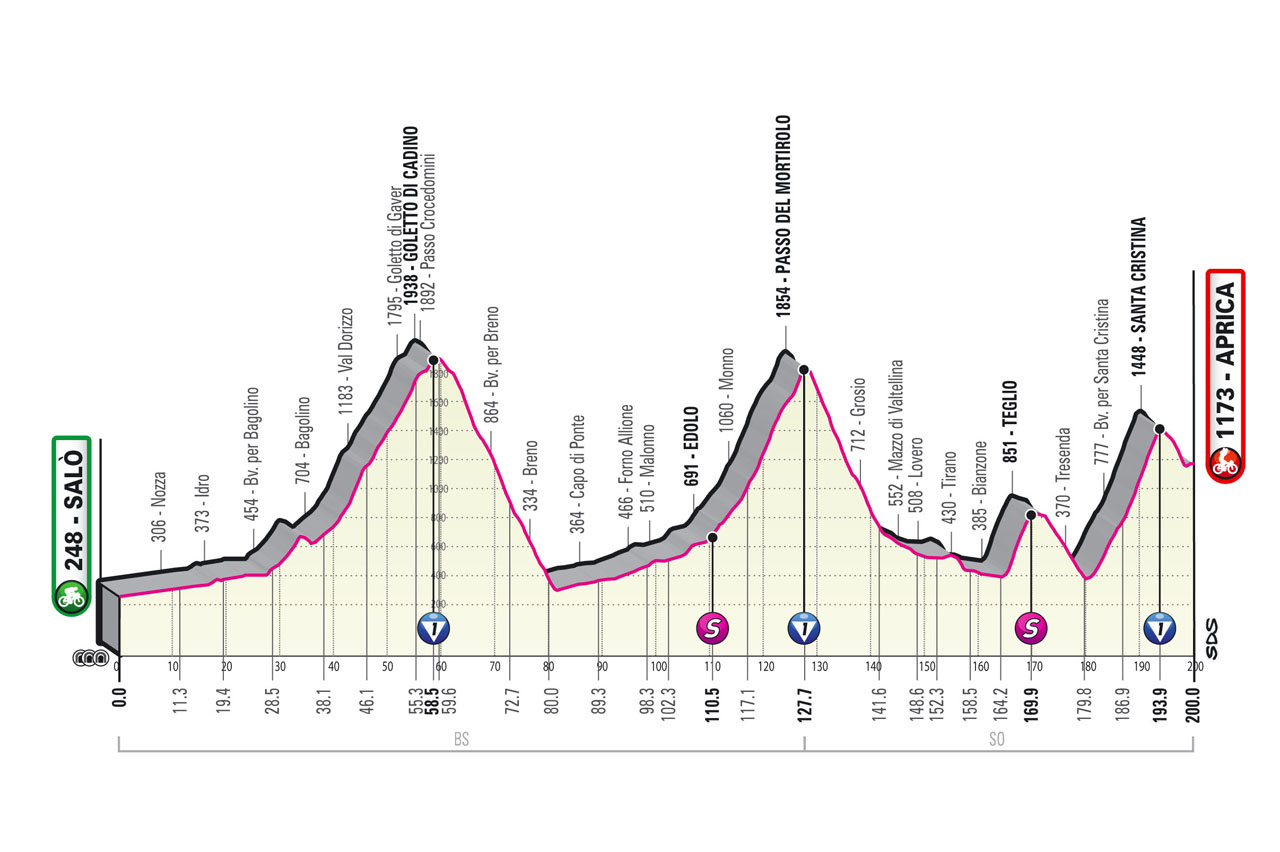

Stage 16: Salò – Aprica, 200km (May 24)

As ever, the principal difficulties of this Giro are positioned in the last week of the race, and there is a typically brutal return to business after the third and final rest day. The 200km leg in Valtellina also serves to promote the local Sforzato wine, and perhaps it’s only fitting that a day with 5,440m of climbing should be accompanied by a glass of a beverage that translates literally as ‘strained.’

The stage gets underway on the shore of Lake Garda at Salò before following the Val Sabbia as far as the day’s first ascent, the category 1 Goletto di Cadino, which makes its third appearance on the Giro after back-to-back airings in the 1990s. Gianni Bugno led over the top in 1997, while Niklas Axelsson was first up here 12 months later, though the day is best remembered for Marco Pantani’s duel with Pavel Tonkov on the final ascent of Montecampione.

Next on the agenda is the Mortirolo, and although it’s climbed on this occasion via its ‘easier’ approach from Edolo, that’s all relative in this particularly jagged corner of Lombardy. The climb via Edolo caused consternation when it first introduced the Mortirolo as a concept on the 1990 Giro, with Leonardo Sierra was first to the top en route to stage victory, and it will provoke ample difficulties here too. It may not have the gaudy statistics and fearsome mystique of the approach from Mazzo di Valtellina, but the category 1 ascent is 12.6km at an average gradient of 7.6%, with pitches of 16% approaching the summit.

After a treacherous descent, the road climbs again towards the intermediate sprint at Teglio before the gruppo tackles the day’s final obstacle, the category 1 Valico di Santa Cristina, forever associated with Pantani’s defenestration of Miguel Indurain on the 1994 Giro. The Santa Cristina last featured, incidentally, on the day Pantani was expelled from the 1999 Giro for a high haematocrit, with Ivan Gotti inheriting the maglia rosa in Aprica after escaping with Roberto Heras and Gilberto Simoni. One can guess which day RCS Sport’s marketing team will choose to remember when they inevitably brand this as the ‘Montagna Pantani’ for the 2022 Giro.

No matter, the Santa Cristina is a most severe climb, which cruelly seems only to grow more difficult as it draws on. The ascent is 13.5km in length with an average gradient of 8%, but the slopes rarely drop below double-digits in the final 5km. The summit is just over 6km from the finish in Aprica, and the time gaps could be hefty.

Stage 17: Ponte di Legno – Lavarone, 165km (May 25)

The protracted presentation of the 2022 Giro meant that the mountain stages were rather divorced of context when they were first unveiled, but now that the hazy picture of this year’s race has finally sharpened into focus, the significance of stages 16 and 17 has become clear. Remarkably, these are the only back-to-back high mountain stages in the entire race, even if the uphill finish to stage 19 is hardly a gentle preamble to the Dolomite tappone that follows.

Coming immediately after the tough leg over the Mortirolo and Santa Cristina, there are sure to be weary limbs and fraying minds in the pink jersey group, and even if the terrain is perhaps not quite as daunting on the road to Lavarone, the potential for big changes in the GC is probably greater, as cumulated fatigue begins to exact a toll.

The road climbs immediately after the start in Ponte di Legno, taking in the steady haul up the Passo del Tonale. The 8.8km ascent is not classified, but few will appreciate such a sharp start to the day’s proceedings, though the long, long drop towards Moser country in Palù di Giovo should mitigate that early difficulty.

The undulating run through the Valle di Mocheni serves as a precursor to the day’s main obstacles, the category 1 ascents of the Passo del Vetriolo and the Salita del Menador. The Vetriolo has featured before, albeit from the opposite side, with Andy Hampsten winning a mountain time trial in 1988 and Julio Jimenez twice leading over the top in the 1960s. This time out, the Giro climbs the Vetriolo from Pergine Valsugana before dropping to Levico Terme.

The great novelty, however, is the short (6.2km) but sharp category 1 ascent of the Salita del Menador, a tightly packed clutch of hairpins and tunnels carved into the rock face as a supply line by the Austro-Hungarian Kaiserjäger regiment during World War I. That sinuous road was subject to significant widening over the past year, prompting speculation that the Giro might be on the way. Or, as local newspaper L’Adige put it when the route was unveiled: “That explains the road works.”

The summit of the Salita del Menador at Monte Rovere comes eight, rippling kilometres from the finish at Lavarone, but it’s difficult to envisage anyone dropped on the Kaiserjägerstraße summoning up the strength to force their way back on before the finish on a day of attrition such as this.

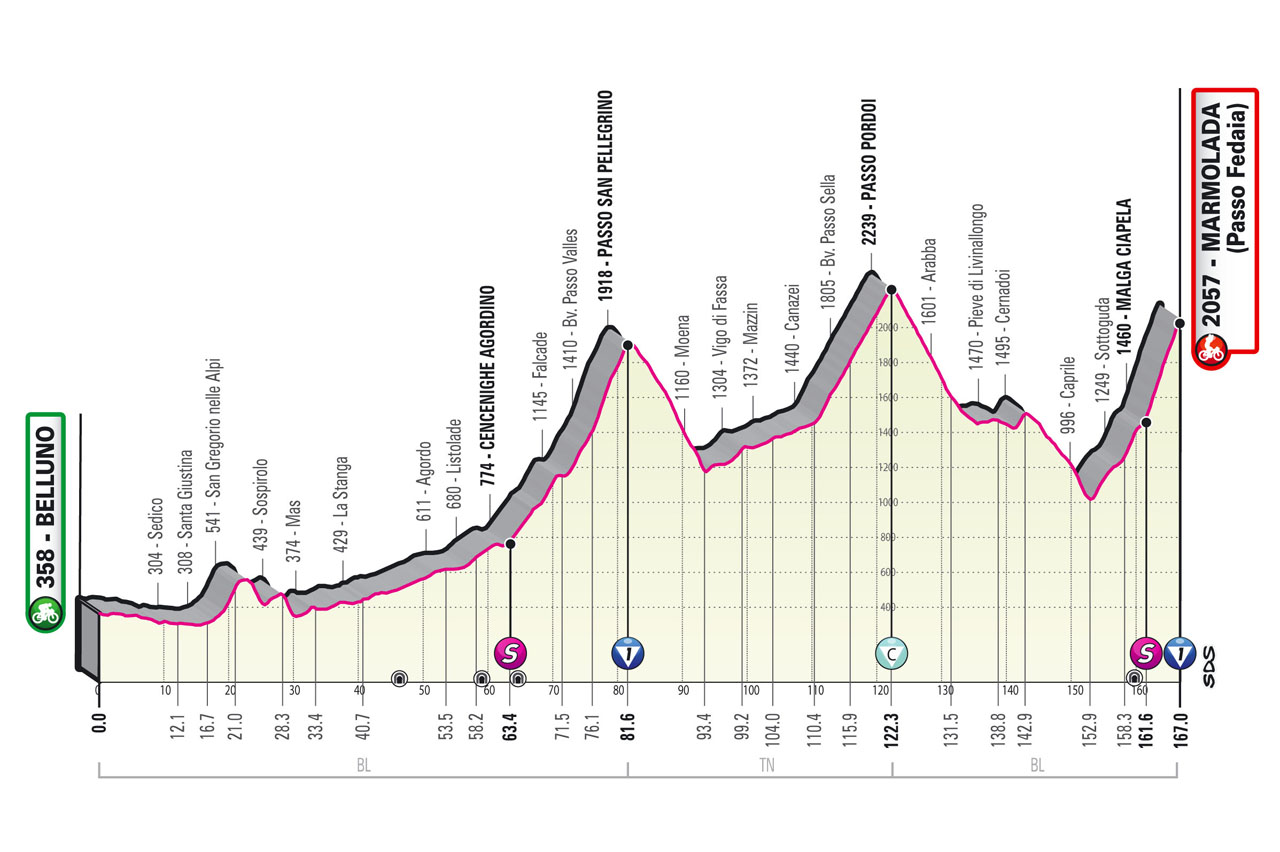

Stage 20: Belluno – Passo Fedaia/Marmolada, 165km (May 28)

There’s still a 17km time trial to come in Verona the following day, and even the shortest races against the watch can make a big, big difference in a modern Grand Tour, but at this juncture, the Dolomite tappone carries all the appearances of the true finale to the 2022 Giro.

The penultimate stage is also, incidentally, the first time the race climbs above 2,000m as it takes in the Passo Pordoi and the Fedaia. Given how the climate crisis seems to have made racing at high altitudes in mid-May ever more hazardous over the past decade, it is perhaps hardly surprising that Vegni waited until the tail end of the month to cross that particular threshold on this Giro.

The Pordoi and Fedaia were supposed to feature in 2021 as part of a 212km tappone with some 5,700m of climbing, but foul weather saw the stage abridged - though not exactly diminished, as Egan Bernal soloed clear on the Passo Giau anyway to put himself in an insurmountable position atop the overall standings.

This time out, the planned Dolomite extravaganza is a little shorter at 165km, though hardly much easier, with some 4,490m of climbing on the programme. The stage has a relatively gentle opening stanza in the Piave valley, but the road becomes altogether more arduous with 100km remaining as the seemingly interminable Passo San Pellegrino rears into view. The category 1 ascent drags upwards to an altitude of 1,910m, and its stiffest, 15% slopes section come inside the final 10km.

The drop to Moena and the rather false flat towards Canazei are followed by the Cima Coppi of the 2022 Giro, the mighty Passo Pordoi, which climbs for 11.8km at an average gradient of 6.8%. The 2,239m-high Pordoi has been a fixture on the Giro since 1940, with Fausto Coppi first to the top on no fewer than five occasions in those early years, and the history of the place both inspires and intimidates.

The same can be said of the Passo Fedaia, which – weather permitting, of course – returns to the route for the first time since 2011. The ascent towards the rocky precipice of the Marmolada made its first appearance in 1975, but it has only been used as a summit finish on one previous occasion, when Emanuele Sella – soon to test positive for CERA – claimed part of his hat-trick of mountain stage wins here.

The Fedaia is 14km at an average gradient of 7.6%, but, as ever, the numbers only hint at the true nature of this beast. Above all, the Fedaia is haunting because of the geography of the place and configuration of the road, most notably the seemingly incessant straight at Malga Ciapela, which starts with a little under 6km to go and where the gradient clicks into double digits and then dials all the way up to 18%, with little to no sign of relief on the horizon. It’s something akin to cycling’s Strait of Magellan. Cruelly, this Giro’s most turbulent waters come very close to the shore.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.