Nairo Quintana: On equal gender-rights and winning the Tour de France

Tour de France coundown: 9 days to go

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

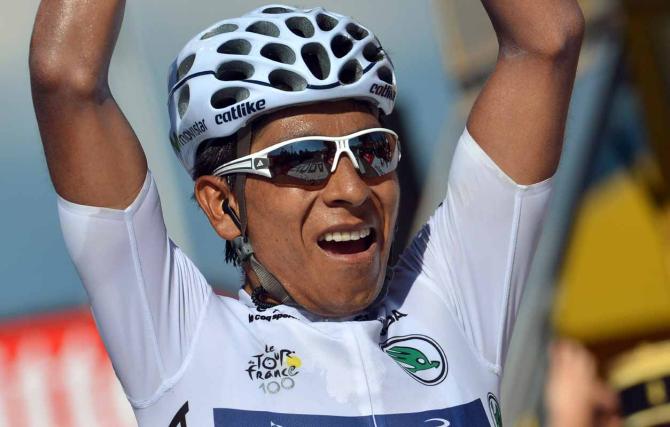

He's a tyrant on the bike yet a man of the people off it. Procycling meets the quiet Colombian who is widely tipped to ascend to cycling's highest throne this July.

Quintana samples the cobbles at Dwars door Vlaanderen

Quintana to tune up for Tour de France at Route du Sud

Quintana: Up to 10 riders could win this year’s Tour de France

Quintana avoids a showdown with Contador at the Route du Sud

Froome: Every day is like a Classic during the first week of Tour de France

The biggest battle Nairo Quintana is fighting is not the one for the yellow jersey at the Tour de France. The Colombian rider is fiddling with a phone during his interview with Procycling but he's not browsing the net while half-heartedly answering questions. Having got on to the subject of what he does when not on the bike, Quintana is looking for images of a pro-equality gender rights television campaign in which he has starred.

He finds what he is looking for, and a tiny image of Quintana fills the screen. "Fighting for women's equality starts in the home," Quintana observes in the video he shows, not a little proudly. It's part of a campaign in his home region of Boyacá, centring on images of Quintana, a national hero and epitome of male athletic success in his country, changing his baby's nappies and then walking round the garden carrying his child.

"My goal is to win the race against social inequality. Just because you do housework, it doesn't mean you're any less of a man," he explains to the cameras. Indeed, apart from the first five seconds when he introduces himself as 'Nairo Quintana from Movistar', on the video there isn't a trace of bikes, races or anything connected to Quintana's job.

Fighting for women's equality isn't the sort of extra-curricular activity you would expect a WorldTour professional to have, given they're often criticised for living inside the bike racing bubble, out of touch with the real world. But then a glance at his Facebook page shows that Quintana actually has a keen interest in social rights campaigns of all kinds, to the point where he has been named an ambassador for UNICEF. Other internet videos show that when the equal rights for women campaign got underway in Boyacá, Quintana stood up in a packed theatre hall, gave a lengthy keynote speech and then handled the media afterwards, with only a cursory mention that he rides a bike to make a living.

"Colombia has social problems," Quintana explains to Procycling. "But even if they're not as serious as in a lot of other countries, that shouldn't stop us from trying to get rid of them completely." It turns out he works in civic education programmes for young adults, too. "We want to be sure they are not just good at maths but that they are good members of society as well," Quintana observes. “And it's up to fathers to educate their kids like that, not just the mothers."

Making history for Colombia

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Cycling fans should rest assured that despite the dedication he shows towards his extra-curricular activities, Quintana shows no sign of losing interest in his big racing goal for the summer: winning first ever Tour de France for Colombia. Indeed, just as in his social campaigning, Quintana is taking his smashing of one of Colombia's longest-standing sporting glass ceilings very seriously indeed.

Quintana's last performance in the Tour, in 2013, was an impressive starting point for this July's Tour bid, two years on. Nominally Movistar's plan 'B' for the 2013 race behind Alejandro Valverde, Quintana outshone his teammate to the point where Quintana was the only rider able to stay even remotely close to a rampaging Chris Froome on the climbs. After opening up hostilities with a long-range and spectacular, if fruitless, attack in the Pyrenees, Quintana finally finished second overall – the first rider since Jan Ullrich in 1996 to finish runner-up in the Tour in his debut. He also came away with a stage win, the best young rider's jersey, and the king of the mountains jersey. Quintana was also the youngest winner of the mountains competition since Charly Gaul in 1955.

"Compared to 2013, I'm more mature, more experienced, and now I think I can fight for the victory," Quintana tells Procycling, in his usual solemn gravelly voice and with his typically sphinx-like facial expression. It makes him sound and look almost like he's uttering prophecies, not talking about sporting goals.

"I don't know my upper limit yet but my mentality has changed in any case because in 2013 I was working for Alejandro. I was a domestique. Now I'm on a different level, looking for different things," he says. "You don't get on a podium of a Tour de France by chance and now I'm going to go in hard for this year's Tour. Just because I'm lacking in experience, it won't stop me fighting for that title," he continues.

"I'm going to be in good shape and I have a good team to support me. The first week may be very intense and nervous compared to other years but the second and third weeks have so many mountain stages, they will benefit me compared to my rivals."

The challengers

Interestingly, Quintana does not put Froome on a higher level than the rest of his opponents, even though the Briton defeated him in each of their 2013 Tour de France mountaintop duels except the very last, at Semnoz, when it made no difference to Froome's overall victory.

"[Thibaut] Pinot, [Vincenzo] Nibali, Froome and [Alberto] Contador are my biggest rivals, you can't rule any of them out in any way. As for Froome's attacks in the mountains, we'll have to go for a strategy that means we can control them as best as possible, and look for the way that they don't affect me so much.

"Anyway, having a Grand Tour in my palmarès now is a huge plus. I've been a leader in that race and in others, and I've done well all round, so this is a good Tour de France for me."

Winning the Giro d'Italia last year certainly confirmed that Quintana was no one-hit wonder. But arguably it was his performance this March, blasting away on the toughest climb of Tirreno-Adriatico - the Terminillo on stage 5 - that underlined his status as one of the top four favourites for the 2015 Tour. That performance was even more impressive given that two of the riders he left standing on that snow-hit ascent were none other than Contador and Nibali. Then, in his one encounter with Froome prior to the 2015 Tour de France, at the Tour de Romandie, neither he nor Froome were at their best. But among all the 'Big Four', Quintana's ride on Terminillo was far and away the standout performance of the early season.

"All four of us are more or less on the same level," is Quintana's guarded comment. "But for me, winning Tirreno was very important, especially after crashing in the [2014] Vuelta, when I abandoned feeling extremely unhappy. After that I had spent such a long time either not racing or not riding in big races. I always knew I'd come back but at the same time, I didn't know in what kind of condition, what kind of level and above all when. But now I have done that race and won it, so that’s a big plus for me."

As for the type of attack he made on the Terminillo, bounding away up the climb with a seemingly unmatchable acceleration, Quintana says, "It's something natural, not something you can train yourself to do. But sometimes, as I do, you have to practice them so your body gets used to it."

An enigmatic man

On paper, the 2015 Tour de France route suits a born climber like Quintana who can also hold his own in the time trials and, as we saw in a surprise appearance in Dwars Door Vlaanderen, can get through the cobbles. Yet, of the Big Four candidates for the Tour, Quintana is the most enigmatic, the least well known, even compared to Nibali, who is no slouch on that front.

This is not just because Quintana is, at 25, the youngest. It's also because he is, by his own admission, extremely shy. "Interviewing him on the telephone isn't ideal. He's a man of few words," is how the press officer at Movistar, his team since 2012, puts it. And indeed in 2014, Quintana lost a major European race – he won't say which – because, he claims, he was too tongue-tied at the morning's team meeting to put across his own point of view about how it should be tackled strategically. So Movistar rode the decisive stage with a DS's tactics, and they lost.

Part of the reason for the aura of mystery surrounding Quintana may be that he has, as one Movistar staff member tells Procycling, "a personality that's so calm and quiet it's almost spooky." But another element is that Quintana hails from very unfamiliar territory for most cycling fans, even in his own country: deepest rural Colombia.

Combine the two factors and the image the more sensationalist elements of the Colombian media have consequently painted of Quintana is as a penniless rural backwoods boy-done-good. But that image, while containing a few grains of accuracy, is well wide of the mark.

It's been widely reported that for three years as a teenager, Quintana would ride up a 16-kilometre climb to go to school in a neighbouring village every weekday. There have also been reports that as a baby he suffered from 'Dead Man's Disease', an apparently life-threatening condition, which according to local Colombian folklore is caused when a pregnant woman, in this case Quintana's mother, is touched by somebody who has recently had contact with a dead person.

But while he rode more than 1,000 vertical metres a day for five days a week during his youth, he did so because he liked riding his bike, not because – as has been incorrectly reported – his family couldn't afford the bus fare. As for the 'Dead Man's Disease', Quintana suggests that chronic stomach upset was more likely to be the case. "Every kid in the world gets sick at some point or another," he said in an interview last year.

Quintana is also keen to underline that growing up in the country and working from a young age does not mean that he had an impoverished agricultural background. Rather, helping in his family business delivering fruit and vegetables when he was a teenager simply meant that he learned the value of working hard from an early age. Quintana believes this so firmly that while helping out with bike clubs in his region, he will reportedly not give the clubs free bikes, arguing it is better for the young amateurs to learn how to fight harder for their objectives, as he had to do.

Quintana feels part of the reason he has been labelled a Colombian redneck is that, as he told Colombian magazine Bocas in an interview last year, "Because we're from the country, they [the media] take it for granted that we're poor. Okay, so we didn't have money for luxuries in my family but we had money for the basic essentials. Maybe not to say, 'I'm going to buy this watch or mobile phone'. But for basic stuff, there was enough." His family's homestead, he points out, was "owned, not rented."

From Boyacá to Paris

Quintana's deep roots and pride in rural life, his shyness and the fact that when he talks – like when he rides his bike – he makes every word or pedal stroke count is, in fact, oddly reminiscent of Sean Kelly. And like Kelly, ever since an early age, Quintana has rarely failed to impress. This started with his first top result in Europe in 2009, aged 19, at the now-defunct Subida de Urkiola race, a prestigious 'revenge match' race held 24 hours after the Clásica San Sebastián, which concludes on one of the steepest summit finishes in the Basque Country. Riding for his tiny South American squad against the likes of Euskaltel-Euskadi and Movistar, Quintana finished seventh.

As Quintana recalled, "I was pretty young and I'd only just turned pro that summer. To be honest, I never imagined it but that [race] was where I started taking my first steps. That result opened a lot of doors for me."

Quintana won the Tour de l'Avenir in 2010 and took the climber's classification in the Volta a Catalunya the following year, against WorldTour opposition. He signed for Movistar in 2012.

Movistar DS José Luis Arrieta recalls Quintana making a strong start to his WorldTour career that year. "As soon as he turned up in the Tour of Murcia that year, that he was able to win the first summit finish was surprising enough. But he'd already won a mountain stage in the Tour de l'Avenir by then, so what really caught our attention was how he then held his own in the Murcia time trial the next day."

The lack of a long time trial in the Tour is "definitely a plus for Nairo compared to Froome or Contador," Arrieta recognises. "He has learned a lot so far about Grand Tour races but you have to remember that it's been a very steep learning curve and he's not able to learn everything as fast as he'd like. This year's going to be another year of learning, even though everybody expects a lot more."

The problem will probably be managing that expectation, given that Quintana has created a huge impact in a relatively short space of time. It's worth remembering that in 2009, when Quintana first came to Europe, Contador had already won all three Grand Tours, Nibali had a top-15 place in the Giro d'Italia and top-20 in the Tour de France, and Froome had completed his first Tour as well. Six years on, he's regarded as a joint favourite on level terms with them.

However, to some cycling observers, that comparative inexperience is all but irrelevant. "He's going to be the first ever Colombian to win a Tour de France," predicts Spain's Pedro Delgado, who spent a fair proportion of his career battling against Quintana's idols such as Fabio Parra and Luis Herrera in the 1980s. "I don't know if it'll be this year but it's going to happen for sure. He's got a decade of good cycling ahead of him." Starting this July, perhaps?

To subscribe to the Cyclingnews video channel, click here

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.