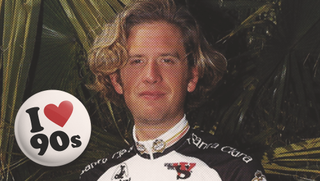

Jonathan Vaughters: The Infamous 1990s

‘Omerta? Not in 1994, baby!’

The following feature forms part of our 'I love the 1990s series' and sees Jonathan Vaughters open up about his first year in the European peloton and the doping culture ingrained in the sport at that time.

Gilles Delion and the road not taken

Remembering Gianni Bugno's 1992 Worlds win

I love the 1990s – A look back at cycling's decadent decade

Robert Millar: A peloton at two speeds and a new breed of climbers

Alvaro Mejia: I would have liked to have raced in a clean era

The 1990s have garnered infamy in professional cycling… and having raced in that decade, I can firmly testify that such infamy is well deserved. Professional cycling was the Wild West back then; financially, organizationally, medically… It was a time of honor among thieves at best and downright insanity at worst.

The mid-1990s were probably the worst time to be a professional rider with none of the charm and gentlemanly behaviour of earlier eras and all of the commercial pressure of later eras. Combs in the back pockets? Sharing cigarettes in races? Forget about it. This was the dawn of the age of big-money sponsor and big-money contracts.

If you wanted to race professionally in the 1990s, you had to be a sporting survivor. A gritty and nasty bastard willing to hop a few fences to make it happen. Idealists were thrown out the passenger doors of team cars and left for dead in ditches. I would never choose it for anyone nor for myself. Unfortunately, we don't get to choose when we are born, and I had a foolish dream to become a real bike racer.

My time in the 1990s and in professional cycling began via the road less traveled. As opposed to the route that most of my contemporaries in American cycling would take (US national team to Motorola and onward from there). I was destined for a much more uncomfortable trip. It started with me finishing second place overall in the 1993 Vuelta a Venezuela. This little result captured the attention of a startup Spanish team I'd never heard of.

A few awkward phone calls and faxes later, I signed a contract, of some sort, to go and race for an amateur team in Spain. I bought a one-way ticket to Spain with the last dollars I had to my name and watched my parents roll their eyes over this very poorly thought out idea.

Still, they drove me to the airport.

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Upon arrival in Spain, I was sent to a laboratory in Pamplona to be tested by the legendary Dr. Pepe Calabuig. I knew of this guy as the one who tested Miguel Indurain's enormous Vo2 max — maybe one just beholds a Vo2 like that? — and was duly nervous to be examined by such a legend.

Blood tests, EKGs, Vo2 max tests, and echocardiograms filled out the day. By the end of it, Dr. Calabuig and my new director called me into a meeting. I figured it was to give me the bad news that I was unfit to be a professional cyclist, and that I needed to go back to Colorado. Instead, Calabuig started excitedly speaking in an odd, somewhat Scottish-accented English telling me about "Enorm ventricle. Left ventiriclo enome! Big heart! Fast in mountains! Big power…. And maybe someday big money!"

Apparently, my left ventricle had 'left' an impression on the lab folks, and they slid me a pro contract across the table to sign along with a printed echo image of the left ventricle. It was like what most people see when they find out if their baby is a boy or a girl, except in this case, size did matter.

I'd never raced one single day in Europe as an amateur, and here I was signing a pro contract due to a large left ventricle in my heart. I couldn't wait to cash that first check. All $1,500 of it.

Half of this odd Spanish team I'd signed for were post-Perestroika Russians looking to make some scratch racing bikes and the team management rented us all a big house outside of Valencia. We were like one big happy family, except for the one time they told me vodka would cure my flu. I quickly learned that though I may have had a big left ventricle, these guys could kick my ass six ways from Sunday on each and every training ride, and if I didn't wash the dishes, I was also going to get my ass kicked in a different way.

They were hard as nails. I was not hard as nails. I was there living out my boyhood dream of becoming a bike racer, with color and crowds and beautiful mountain passes. They were there because they needed jobs, they needed money, and they wanted ways out. Racing was about getting paid, and the ends always justified the means. Welcome to the real world, Colorado boy. This was my first life lesson in cultural and moral relativism that I'd so comfortably debated in philosophy class the year before.

My first race would be Semmana Catalana, which no longer exists, but was conquered by many of the greats; Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche, Andy Hampsten, Gert-Jan Theunisse, and Miguel himself.

I figured I'd do pretty well, as I had a big left ventricle, and I'd been training pretty hard with my little band of Russians. Boy was I wrong. I was the worst rider in the race uphill, on the flats, downhill, in the dry, in the rain, in the heat, or in the cold. The worst. No question. While my heart rate was absolutely pegged at maximum, I watched riders around me still chatting, and one Mapei rider who, right when the race would start to split apart on a climb, would sit up, take his hands off the handlebars, make a Schwarzenegger-esque flexing pose and start yelling something in Spanish at full volume.

I was used to being the young phenom talent of the high Rocky Mountains. Now I was a garbage rider taking up space in the last five riders of the peloton and suffering as other riders conducted super-villain monologues while riding no hands.

Stage after stage I suffered this indignity and quickly developed a level of fatigue I'd never imagined could exist. I hurt everywhere. After four stages of racing that was clearly way over my head, I'd had enough. So I quit.

I arrived at the finish in a car. Instead of receiving some sort of consolation or pep talk, my director spit angry words at me: "You better damn well ask permission to drop out of a race before you pull this shit! I don't care if you're bleeding out your ears from an aneurysm, you don't put a foot on the ground until I tell you to. And you think you're getting paid this month!?"

This could not be further from the tofu-eating Boulder bike culture I grew up with.

Out of stubbornness and fear of returning home and being ridiculed by friends and family, I kept at this futile endeavor. With a lot of training, as opposed to relying on my left ventricle, I started to improve enough to at least finish races. Barely.

My Spanish was also improving quickly, so I could actually understand what was being said during these casual 400-watt conversations on climbs. And boy did that change my take on things. The major point of discussion was dosages, doctors, and doping. Omerta? Not in 1994, baby! Doping was openly discussed at the dinner table, during the race, during training rides, and on the massage table. Remember, this is pre-Festina scandal, pre-police raids, pre-EPO test, pre-blood doping test, pre-50 per-cent hematocrit test, pre-Floyd fairness fund, and pre-Oprah.

There was no reason to keep doping hidden from anyone in 1994, as it was an open topic and open season. This was cycling's version of pre-Geneva convention warfare. An unmitigated and uncontrolled arms race. There were no effective tests, few controls period, and certainly no moral judgment. It was simply a fact of the sport.

The chattering complaints from the riders in the Spanish race peloton weren't about doping being an issue unto itself, more that it was getting expensive and that some teams were making the riders pay for doping with their own money. Bastards. Oh, and it was never referred to as doping, but instead "medicine" or "sports medicine."

Right. Got it. Sports medicine.

The gravity of all this didn't hit me immediately. I was more concerned with very basic survival in life and in the peloton.

Also, my team manager was a celibate member of Opus Dei and deeply religious, so initially, he was very opposed to "sports medicine." A bit of an odd man, always dissuading me from talking to girls, but he really did his very best to shelter younger riders from the hard facts. So, he kept telling me to not worry about the "medicine" chit-chat. Plus, even amongst the other teams in the Spanish peloton there was some sort of unspoken rule that you needed to race your first year or two in the pro ranks clean, just to see if you could hang on for dear life, before you were let into the high-octane club. I was told to start riding my bike more and stop listening to conversations in the peloton. The "medicine" I was told, wasn't that important for a neo-pro.

My Russian roomies were given the same speech. I could tell they thought it was a bunch of bullshit. By the time 1996 rolled around, the team manager had conceded the point and convinced himself that a bit of "medicine" would be OK with the Holy Trinity and the Catholic church. Plus, I was a third-year pro by 1996, so it was OK by all accounts.

All of the above makes me giggle when I hear folks chatting about how bad the doping issue is in sports nowadays. I simply think to myself "man, you have no idea of what 'bad' really is. Nowadays ain't nuthin compared to the mid-90's!"

The team let me go back to the US for the month of July in 1994, because for a team that doesn't do the Tour de France, not much happens in July. After a few days of speaking to people I hadn’t spoken to in months, like my poor mother and my long-suffering girlfriend, I decided to go to the Tour of the Gila for a bit of a walk down memory lane and to keep me in shape. Turns out that racing back in the USA in the 1990s was a whole lot different than what I'd just been through. The US races were like a nostalgic time warp back to a simpler time in cycling. While I started Gila thinking I was an absolute steaming turd of a bike racer, it turns out that I was, instead, the best climber, the best time trialist, the best on the flats, the best in the heat, the best in the rain. I won the race with relative ease and was left wondering what the hell was wrong with me in Spain.

Upon my return to the Old World, I felt as fit as a fiddle and full of motivation after my dominating exploits back home.

That attitude got reality checked very quickly, as I once again suffered like a pig caught in a fence. But hey, this time, as opposed to suffering 180 riders back in the peloton, I'd improved enough to suffer only 80 riders back. This painful mid-packness, in my mind, justified my decision to forgo a higher education, break up with my girlfriend, and continue to worry my poor mother.

The other great thing was that I was finally close enough, and spoke enough Spanish, to understand what the crazy guy would start yelling while doing his body builder poses on the climbs. Every time it would start to go full gas up the climb, he'd rear up on his bike and yell "Viva la quimica!!! Estoy tan fuerte o la quimica me ha hecho asi??? VIVA LA QUIMICA!!!" Which roughly translates to "Long live chemistry!! Am I really this strong or have the chemicals made me like this?? Long live chemistry!!!"

And this, roughly translated, is my version of the 1990s in cycling.

Viva la quimica, indeed.

Thank you for reading 5 articles in the past 30 days*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read any 5 articles for free in each 30-day period, this automatically resets

After your trial you will be billed £4.99 $7.99 €5.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just £49 $79 €59

Join now for unlimited access

Try your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Most Popular