Flat-bars or drop-bars at Leadville Trail 100 MTB? This high-altitude endurance race doesn't have a handlebar problem, it has an identity crisis

'Courses dictate our equipment choices' as Lauren De Crescenzo and other riders dissect the 100 miles of Leadville regarding safety issues, equipment setups and a solution

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

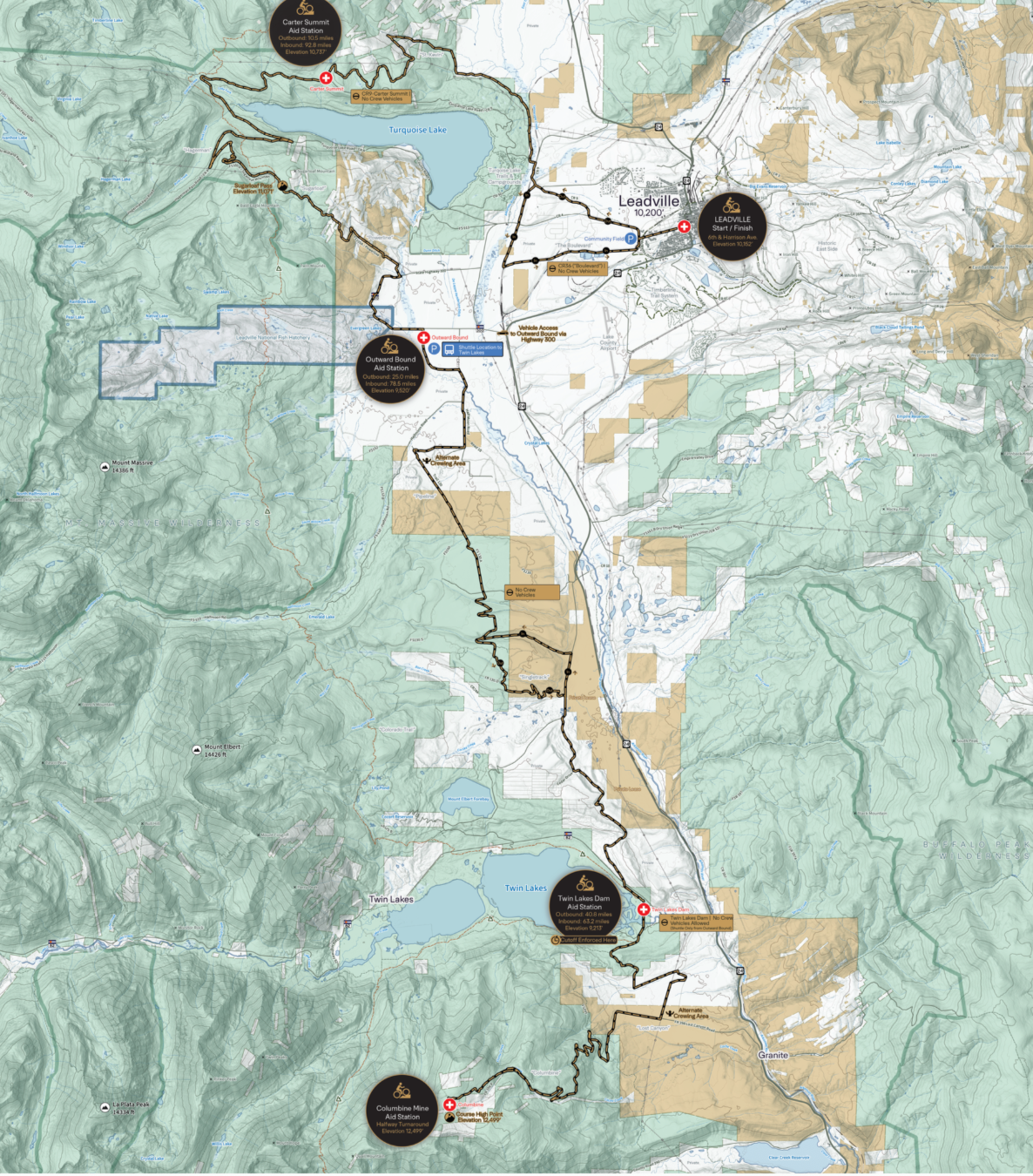

Every few years, riders expose how efficiently Leadville Trail 100 MTB can be raced. The high-altitude, endurance mountain bike race in Colorado has gained more attention since becoming a high-stakes round in the Life Time Grand Prix.

So when riders expose efficiency, like recent winners Keegan Swenson and Kate Courtney setting course records, Swenson doing so in 2024 for the elite men and Courtney last year for the elite women, the conversation shifts from celebrating performance to protecting identity.

This year’s identity crisis? Handlebars.

The flat-bar versus drop-bar debate didn’t erupt because riders suddenly forgot how to mountain bike. It happened because Leadville quietly rewarded efficiency, punished impatience, and exists in a gray zone between gravel, road and mountain bike.

On a course dominated by long dirt roads, sustained climbs and a fast pavement finish, aerodynamics and pacing matter.

When five-time Leadville winner Swenson first won the race on drop bars two years ago. It wasn’t a gimmick; it was a statement. When Dylan Johnson, a three-time US National Ultra Endurance Series winner, ran the numbers and showed that smoother pacing and aero efficiency could save real time over 100 miles. It wasn’t theory; it was drag coefficients.

Payson McElveen, who has finished in the top 5 five times with two podiums, looked at the safety concerns. Different bars mean different braking points, different descending speeds, and different risk tolerances. In a fast-moving pack always above 10,000 feet, unpredictability matters more than marginal aero gains. From that lens, standardising equipment isn’t anti-progress, it’s pro-safety.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Alexis Skarda is a three-time US Marathon Mountain Bike champion and has been on the podium at Leadville as a Life Time Grand Prix contender, and she cut through the whole thing with refreshing honesty: "This debate is stupid."

She’s not wrong. We’re arguing about handlebars because the course itself is sending mixed signals.

The 'VIP meeting'

I was in the room when the handlebar discussion happened, which is referred to now as the 'VIP meeting'. No conspiracy, just 15 Life Time Grand Prix racers attempting to solve a real problem. The request for a rule change was initiated by us, the riders using the course.

So how do mixed handlebar setups change the dynamics of riders moving through one specific race, Leadville Trail 100 MTB, especially when altitude and fatigue strip away margins?

McElveen articulated safety concerns about different equipment, especially with braking on descents.

Others in the room, without the same resources as the top riders, raised a different issue about the switch to a drop-bar setup, which isn’t trivial. It’s expensive, logistically complicated, and often requires additional support that not everyone has access to.

"Among the many suggestions, doing away with drop bars at Leadville had near unanimous support," McElveen wrote on his Instagram feed to clear the air a couple of weeks ago.

"And, maybe even more surprising to some of y’all, it was Keegan Swenson who brought up the consideration of fairness. Getting a drop bar MTB to work usually requires getting an extra frame and going down a size, a luxury not everyone on the start line has…especially younger up-and-coming riders."

As for me? I’m not a mountain biker by trade. I was a roadie who picked up the discipline in the latter part of my career so I could compete in the Life Time Grand Prix. I like the wider platform of flat bars because I feel more control over the bike. At the same time, I don’t want to be racing next to riders in the drops. It’s the same way I feel riding next to a time trial bike on my road bike on a group ride: different hand positions, reaction speeds, different brake modulation.

By the end of the meeting, there was no formal vote. It was more of a vibe. The room swayed towards banning drop bars.

Standardise the equipment. Standardise the handling. And may the best legs win. But does that logic hold up?

Life Time is the UCI of gravel, whether we like it or not

Cecily Decker finished third at Leadville on drop bars, using the top result to finish second overall in the Grand Prix in October. She wasn’t in the meeting, however. She didn’t have a vote. And she didn’t get to weigh in on who did. Her frustration wasn't about the decision itself, but about representation.

“I was not present at the ‘super secret meeting’ of athletes when the decision was made, nor did I elect any representatives to be present. As far as the safety concern, considering drop bars, I am not aware of any incidents that were caused directly or indirectly by drop bars,” she said.

That critique is fair. The truth is, Life Time is a private, for-profit company that owns every race in its off-road series. They can make whatever rules they want. They are not required to ask for athletes’ input.

But in a discipline without a true governing body, these decisions inevitably take on more weight. When rules are framed as athlete-driven, the process matters. Broader athlete input, clear communication, and actual voting.

Instead, the process seems a bit ambiguous: a handpicked group and informal consensus.

Breaking the course down, section by section

Let's actually look at Leadville piece by piece. This leads me to say that if the whole course demanded it, riders would self-select flat bars overnight. No meetings required.

Start to St. Kevins: chaos, adrenaline, bad decisions

Flat bars shine here, not because they’re faster, but because they’re familiar. Riders surge, cover moves, and feel in control. Drop bars encourage steadier pacing but can feel awkward in a chaotic group.

Most of the damage done here has nothing to do with handlebars and everything to do with ego. Flat bars make that easier.

St. Kevins to Pipeline: the first test

Long dirt roads make for high speeds. Nothing technical. Aero matters. Smooth pacing matters. Riders on flat bars sit up, push more watts, and burn matches.

This isn’t mountain biking. It’s a rolling FTP test at altitude

Pipeline to Columbine: where discipline wins

On Columbine, flat bars feel nice - an open chest and better leverage for standing bursts. Drop bars reward restraint. Sit, spin, and do not panic.

Neither setup wins here. The rider does. But one setup encourages patience more than the other.

Columbine descent: the safety argument

This is where the safety argument hits the hardest. Descending tired, loose, and oxygen-deprived on drop bars requires focus. Flat bars lower the mental tax. Fewer variables. Fewer moments where one mistake cascades into a heart-rate spike you never recover from.

If there’s a single section that justifies standardisation, it’s this one. Riders are descending tired, loose, and oxygen-deprived after reaching the highest point of the race (12,424 ft / 3,787 m).

On drop bars, that descent requires precision. Hand position, brake modulation, and line choice all matter while fatigue eats away at each.

When fatigue, speed differentials, and opposing traffic converge, safety depends on minimizing variability across fields. Flat bars do that. Drop bars do not. In the most chaotic and consequential descent of the race, standardisation is not about limiting performance. It is about reducing risk when riders have the least capacity to manage it.

Pipeline return and Powerline: fatigue exposes everything

Powerline doesn’t care what bars you choose. It only asks whether you respected the first 80 miles.

The final pavement drag: where the argument comes back

If you’re solo, exhausted, and riding into a headwind, aero isn’t theoretical. It’s survival. Drop bars save watts. Flat bars cost them. That’s physics.

So, do drop bars offer an advantage? Sometimes. In specific places. For specific riders.

Simpler solution for flat bars

What's the simple solution if Leadville really wants riders to just use flat bars? Add more singletrack.

Add technical sections favouring mountain bike handling. When terrain makes drop bars unattractive, there is no need to ban them.

We adapt our bikes to the course. If we want Leadville to be a true mountain bike race, then the course has to demand mountain bike equipment. Right now, Leadville invites optimization, then acts surprised when athletes optimize.

Drop bars didn’t break Leadville. They exposed it.

They exposed a race that wants the soul of mountain biking, the speed of gravel, and the mass-participation of a gran fondo - all at once. That tension will not disappear with the rule change. It just moves to the next piece of equipment someone decides is “too much".

Payson is right about safety. Cecily is right about voice. Alexis is right about perspective.

The handlebar debate isn’t really about handlebars. It’s about whether courses dictate our equipment choices on race day or the race organizers set forth an opaque set of opinion rules.

Until that question is answered, this won’t be the last time we argue about what belongs on a bike at the Race Across the Sky or any other race that exists precisely because it isn’t regulated by an official governing body.

Subscribe to Cyclingnews for unlimited access to our gravel and off-road cycling coverage in 2026. We'll be on the ground at the biggest races of the season, bringing you breaking news, expert analysis, in-depth features, and much more. Find out more.

Lauren De Crescenzo is an accomplished gravel racer, having gained fame as the 2021 Unbound Gravel 200 champion and racking up wins at won The MidSouth (three times), The Rad Dirt Fest and podiums last year at Crusher in the Tushar and Big Sugar Gravel. In 2016, she suffered a nearly fatal, severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) in a professional road race. While the bike almost took her live, she says the bike saved her life as a rehabilitation tool in the following years and she found a new love– gravel and off-road racing. She now wants to be a role model of tenacity, grit, and hard work to promote the vital message of TBI awareness, positively impacting the lives of those affected by TBIs.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.