CIRC finds no proof of UCI corruption but questions linger over governance

Makarov's influence on confederations highlighted as problematic

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Cycling Independent Reform Commission (CIRC) has found that the UCI did not cover up a positive test from Lance Armstrong at the 2001 Tour de Suisse but it has criticised the governing body for failing to open disciplinary hearings against Armstrong and Laurent Brochard for positive tests at the 1999 Tour de France and 1997 Worlds, respectively.

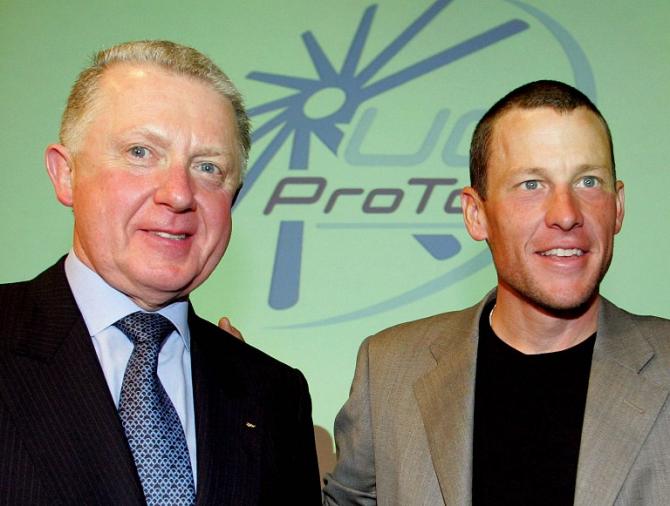

Even before the publication of the CIRC report, former UCI president Hein Verbruggen was claiming that he had been vindicated by its findings. "There is nothing under the table and no indication of corruption," he told Reuters over the weekend.

Yet while the three-man commission cleared the UCI of corruption in relation to the most high-profile allegation, namely that Armstrong had paid to cover up a 2001 positive test, their report describes the American as benefiting "from a preferential status afforded by UCI leadership." CIRC also takes a jaundiced view of Verbruggen’s accumulation of power and ongoing influence through the Pat McQuaid era. The report also voices concerns about Igor Makarov's current influence on the confederations sponsored by his Itera company.

The UCI and Armstrong's lawyers are criticised for their heavy involvement in drafting the ostensibly independent Vrijman report, which examined the accusation – published in L'Équipe in 2005 – that Armstrong had used EPO at the 1999 Tour.

A link is drawn between Pat McQuaid's decision to allow Armstrong to compete at the 2009 Tour Down Under despite not having been part of the drug-testing pool for a full six months and his subsequent, surprise decision to participate in that year's Tour of Ireland.

CIRC also queried why Alberto Contador was informed in person of his positive test for Clenbuterol at the 2010 Tour de France, although it said that it had found no evidence to suggest that the UCI had attempted to cover up the test.

The 2001 Tour de Suisse

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The allegation that the UCI had accepted a financial donation from Armstrong in exchange for covering up a positive test at the 2001 Tour de Suisse was first made public by Floyd Landis and later by Tyler Hamilton, but the CIRC committee found that Armstrong had not in fact tested positive at the race and concluded that Armstrong's donation of $25,000 to the UCI the following year did not amount to corruption.

"CIRC has not found any evidence of corruption in relation to a positive test by Lance Armstrong during the Tour de Suisse in 2001, as alleged by Tyler Hamilton and Floyd Landis in their affidavits to USADA as part of the Reasoned Decision," the report states, adding: “CIRC considers that it is unfortunate that such serious accusations can be made public."

CIRC confirms that the report sent by the Lausanne laboratory to the UCI regarding Armstrong’s samples from 19 and 26 June 2001 describes a "strong suspicion of the presence of recombinant erythropoietin" but notes that “not all the criteria for a positive result were fulfilled." CIRC later notes that one or more samples taken from Armstrong at the 2002 Dauphiné Libéré and analysed in the Châtenay-Malabry laboratory in France were also described as suspect but not positive.

"On the basis of the information in its possession, the CIRC can conclude that Lance Armstrong did not test positive for EPO or any other doping substance during the 2001 Tour de Suisse," the report says. "CIRC has not found any indication of a financial agreement between Lance Armstrong and Hein Verbruggen or, as would follow from the absence of evidence of a positive test, of any attempts by UCI to conceal a positive test by Lance Armstrong at the 2001 Tour de Suisse."

The commission does concede, however, that the UCI "did not act prudently" in accepting a donation of $25,000 from Armstrong in May 2002, which was later allocated to the budget for testing junior and under-23 riders.

Vrijman Report

In August 2005, L'Équipe reported that retrospective analysis of Armstrong's samples from the 1999 Tour showed that he had used EPO, and two months later, the UCI commissioned Dutch lawyer Emile Vrijman to investigate the claim. Earlier in 2005, Armstrong had agreed to make a donation of $100,000 to the UCI – eventually paid in January 2007 – which was used to purchase a Sysmex blood testing machine.

CIRC found no link between Armstrong's payment and the financing of the Vrijman report, but it states that the UCI "had no intention of pursuing an independent report" and highlights the fact that they allowed “the primary subject of the investigation [Armstrong] to participate in the drafting of the report."

CIRC also criticises the UCI for "purposely limited the scope of the independent investigator's mandate" and concludes that both the UCI and Armstrong's lawyers were "directly and heavily involved in the drafting of the Vrijman report." Their objective, CIRC says, was “to ensure that the report reflected UCI's and Lance Armstrong’s personal conclusions."

Brochard and Armstrong's back-dated medical certificates

The CIRC report highlights two instances of UCI impropriety in the handling of doping cases from the late 1990s, namely Laurent Brochard's positive test for lidocaine after winning the World Championships road race in San Sebastian in 1997, and Armstrong’s four positive tests for corticosteroids at the 1999 Tour.

On each occasion, CIRC concludes, the UCI breached its own anti-doping protocol by approaching the riders' entourages and asking them to provide backdated medical certificates when the riders had not declared the use of a substance on their original doping control forms. According to CIRC, disciplinary proceedings should have been opened against Brochard and Armstrong, and the UCI’s failure to do so constituted "a serious breach of its obligations."

Pat McQuaid and Armstrong's 2009 comeback

A lengthy section of the CIRC report is devoted to Armstrong's return to professional cycling in 2009 and, in particular, the UCI's decision to allow him to compete at that year's Tour Down Under despite not having been available for testing for the requisite six months beforehand.

On October 6, 2008, then-UCI president Pat McQuaid sent Armstrong a letter stating that he was ineligible to compete until February 6, 2009, meaning that he would be forced to miss the Tour Down Under. That same day, the CIRC report says, Armstrong decided to participate in the Tour of Ireland, a race organised by McQuaid's brother, Darach McQuaid. Two days later, the UCI publicly announced that Armstrong would be allowed to participate in the Tour Down Under.

According to CIRC, sources and documentation demonstrate that Armstrong's decision to participate in the Tour of Ireland "was linked to the decision of Pat McQuaid to let him race in Australia." Although CIRC says that it has no direct evidence of a quid pro quo between Armstrong and McQuaid, it concludes that "documents in the CIRC's possession show a temporal link between the two decisions."

Contador's clenbuterol case

Although the CIRC report finds no evidence that the UCI attempted to cover up Alberto Contador's positive test for clenbuterol at the 2010 Tour de France, it points to a discrepancy when it notes that three UCI staff members met with Contador in Puertollano, Spain on August 26, 2010 to discuss his positive test.

"This was not the usual procedure," the report states. "The CIRC has not found any other example where this procedure has been followed for other riders." However, CIRC also notes that WADA had been informed of the positive test and concludes that there was "no evidence to show that the UCI tried to hide the positive test of Alberto Contador."

Criticisms of UCI governance and Makarov's influence

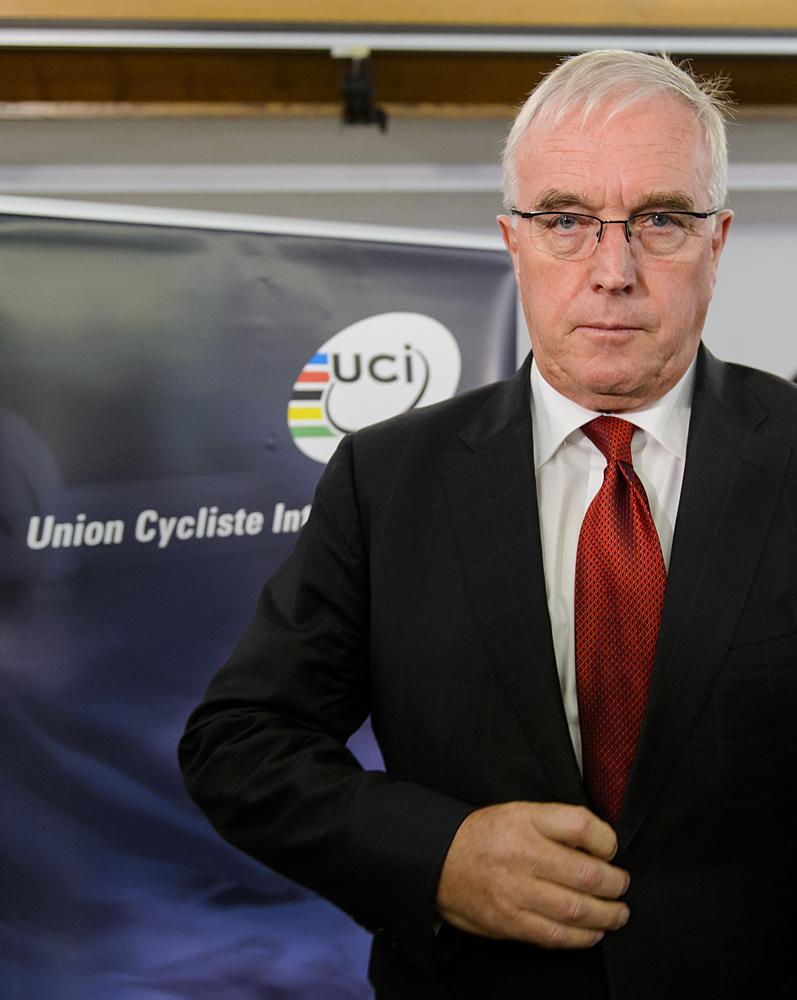

The CIRC report paints a picture of the UCI as something of a dictatorship under Verbruggen's presidency, with one source from the governing body quoted as saying that the Dutchman "was the Management Committee."

CIRC also found that Verbruggen had exerted undue influence on the election of his successor in 2005, particularly when he gave Pat McQuaid a paid position at the UCI in the six months leading up to the election, "without making the post open to a competitive recruitment procedure and without a specific job description."

McQuaid, who was president of the UCI Road Commission, had already accepted a paid position as a consultant to the organisers of the 2004 Worlds in Verona. By agreement with Verbruggen, McQuaid's fees from Verona, totalling €85,000, were paid directly to the UCI. The CIRC reports notes that this money was later used by the UCI “to finance Pat McQuaid's 'training' in Aigle before his election to the office of President.”

Verbruggen’s support of McQuaid's campaign, CIRC states, was in part because of his fear that a candidate sympathetic to ASO might gain control of the UCI presidency. After McQuaid's election, Verbruggen remained in place as vice-president. “Several interviewees confirmed that Hein Verbruggen continued, for some years after the election of his successor, to exercise a decisive influence on major resolutions passed by the UCI," the report states.

An entire page of the section entitled "The casual use of financial resources" has been redacted altogether in the published version of the report. This section later includes criticism of the UCI’s first attempt at an independent inquiry into its handling of the Lance Armstrong case, which it says cost over CHF 2 million for two months.

The CIRC report is also pointedly critical of the influence of Igor Makarov in the run-up to the 2013 presidential election, when he supported the candidacy of Brian Cookson. CIRC describes his employment of private investigators to compile a dossier on McQuaid and Verbruggen as "entirely unacceptable," particularly as he later failed "to give the report to the appropriate organs within UCI (until after the elections)."

CIRC describes Makarov's sponsorship of the European, African and Pan-American cycling confederations as a conflict of interests, noting that the three confederations "account for 30 voting delegates in the presidential election." CIRC concludes by pointing out that Makarov chose not to provide testimony to the commission "despite repeated invitations," preferring instead to send four representatives to two separate meetings.

Recommendations

The CIRC report’s conclusion contains a series of recommendations for the future governance of the UCI, beginning with the suggestion that changes be made to the existing process of electing a president, including the granting of voting rights to representatives of professional licence holders.

The recommendations thereafter are largely vague in nature, however, including the instruction that there should be “better control and accountability for UCI in the form of its overarching management body” and that the Management Committee should "be accountable."

There is a recommendation that the UCI Ethics Commission ought to be independently appointed and "more proactive" and it is suggested that the Ethics Commission's term should not be tracked to that of the president, "so that it cannot be dissolved immediately after an election." It is also recommended that the UCI facilitates a "strong" riders’ union, which would be given a number of votes in UCI Congress.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.