Giro d'Italia: Pitfalls aplenty as the race resumes in Italy

A look ahead at week one's rocky road from the deep south to Chianti

Received wisdom has it that the Giro d'Italia's general classification contenders – with the obvious exception of the unfortunate Jean-Christophe Péraud – will be relieved to have safely negotiated the race's treacherous opening days in the Netherlands, and will have breathed a collective sigh of relief on reaching Italian soil in Calabria on Monday.

A closer inspection of the road book, however, should serve as a warning: the race's early pitfalls are still to come. The Chianti time trial on stage 9 may be, as Giuseppe Martinelli put it, "the most important thing" in the Giro's opening two weeks, but the Astana directeur sportif will be keenly aware that the road from here to Tuscany is a fraught one.

On Tuesday, the Giro re-opens for business with a sinuous trek through Calabria, from the regional capital Catanzaro to the seaside town of Praia a Mare. It is, to borrow the local expression, a 'mangia e bevi' stage; that is, one where the road constantly rolls up and down as it winds its way over the headlands and outcrops of the Tyrrhenian coast.

Although there are just two categorised climbs on the route, the raw statistics are cruelly deceptive. As is so often the case when the Giro visits this corner of the world, there is scarcely a metre of flat over the 200 kilometres, and the stage is rife with potential ambush sites. Small wonder, then, that the stage's difficulty is rated at three stars (out of a maximum five) in the road book.

In many respects, it is not dissimilar to the dramatic stage to nearby Marina di Ascea in 2013, when Bradley Wiggins more or less withstood the first assault from Vincenzo Nibali et al, but learnt the harsh truth that the Giro operates to a different rhythm than the Tour de France, or the rolling day to La Spezia last year, when Ryder Hesjedal lost all hopes of a podium finish as Astana took the race in hand.

Tuesday's finale also includes the uncategorised, 18% slopes of the Fortino. Coming just ten kilometres from the finish line, it might well signal the end of Marcel Kittel's reign in pink – though on current form, nothing seems beyond the German, including a white knuckle descent to get back on – but it could also provide a springboard for willing attackers. In 2011, after all, Alberto Contador make significant gains on a seemingly less demanding finale further down the coast in Tropea. GC contenders beware.

Stage 5 to Benevento is, theoretically, a more straightforward one, primarily because of the flat run-in to the finale that should be manna to the sprinters. Yet the stage is also some 233 kilometres in length and features some heavy terrain as it negotiates the rugged interior of Campania en route to Benevento, including the striking Vallo di Diano, and the uplands of the Monte Partenio region, not far from Montevergine, a climb synonymous with one Danilo Di Luca.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

Summit meeting

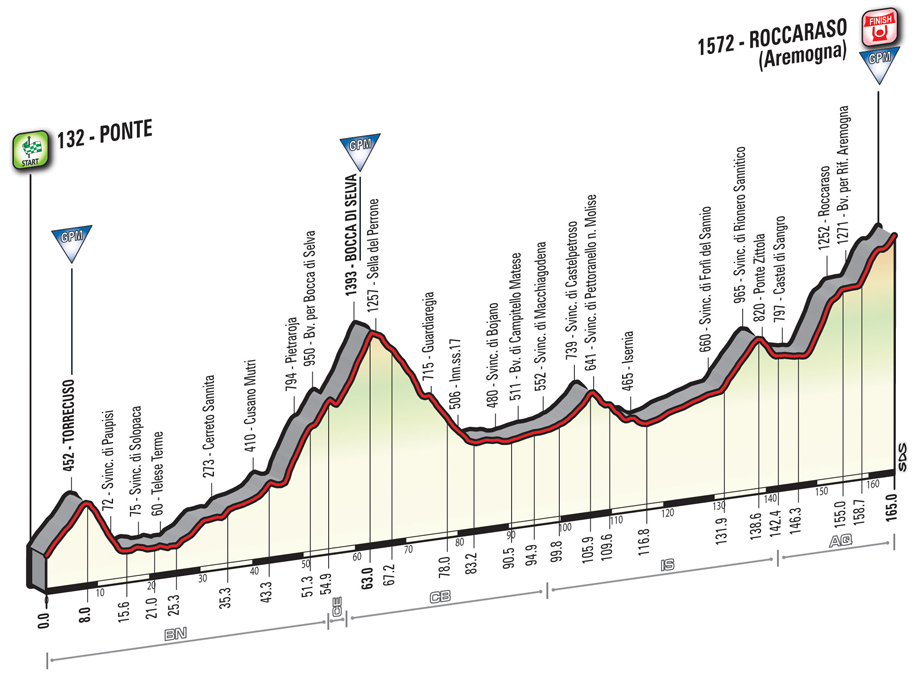

Speaking of Di Luca, stage 6 to Roccaraso features what was his speciality during those years of excess – a medium mountain summit finish in southern Italy. Standing above Castel di Sangro, the town immortalised by the late Joe McGinniss' account of the local football team's season in Serie B, the final climb to the Rifugio Aremogna has not featured in the race since Moreno Argentin triumphed ahead of Franco Chioccioli in 1987, but should nonetheless feel familiar to experienced Giro riders.

17.9 kilometres in length at an average gradient of 4.8% and climbing in instalments, Thursday's finishing climb is not altogether dissimilar to finishes at places like Monte Sirino, Montevergine or Montecassino – tough enough to force a selection, certainly, but perhaps not quite steep enough to cause undue difficulty to any of the bona fide podium contenders. The battle for positions at the base of the climb could complicate matters, along with the forecast for rain. Similar conditions at Montecassino two years ago, after all, sparked the crash that allowed Cadel Evans and Michael Matthews forge clear in a small group.

Rain is forecast, too, for Friday's stage 7 to Foligno, where the flat final 50 kilometres should ensure that the sprinters enjoy another battle, but the rolling early terrain, not to mention the sheer length – 211 kilometres – will deplete resources still further ahead of that all-important Chianti appointment.

And, as is the Giro's wont, there is no relaxed preamble to that time trial. In years past, Arezzo has hosted sprint finishes – Mario Cipollini broke Alfredo Binda's longstanding record haul of stage wins there in 2003 – but this time out, the finale features the climb of the Alpe di Poti, which features gradients of up to 14% and more than six kilometres of unpaved roads. With the summit coming just 18 kilometres and a rapid descent from the finish, the general classification contenders will again be on their guard.

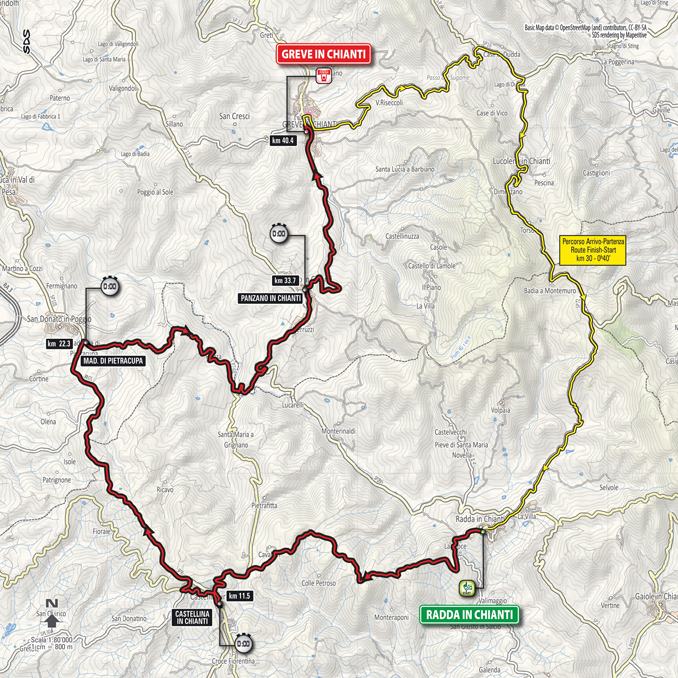

Sunday's Chianti time trial may ultimately prove the foundation for eventual overall victory, but there is plenty of scope for one or more pink jersey contenders to drop out of the running before then.

Twelve months ago, the Astana team waged guerrilla warfare day in, day out during the opening two weeks of the Giro, mindful that their leader Fabio Aru was liable to lose huge chunks of time to Alberto Contador in the Valdobbiadene time trial.

This time around, Messrs. Nibali and Valverde, in particular, will doubtless be minded to put Tom Dumoulin (Giant-Alpecin) on the back foot ahead of the Chianti time trial, though, as the Dutchman demonstrated at last year's Vuelta a España, he is a particularly tough out.

Barry Ryan was Head of Features at Cyclingnews. He has covered professional cycling since 2010, reporting from the Tour de France, Giro d’Italia and events from Argentina to Japan. His writing has appeared in The Independent, Procycling and Cycling Plus. He is the author of The Ascent: Sean Kelly, Stephen Roche and the Rise of Irish Cycling’s Golden Generation, published by Gill Books.