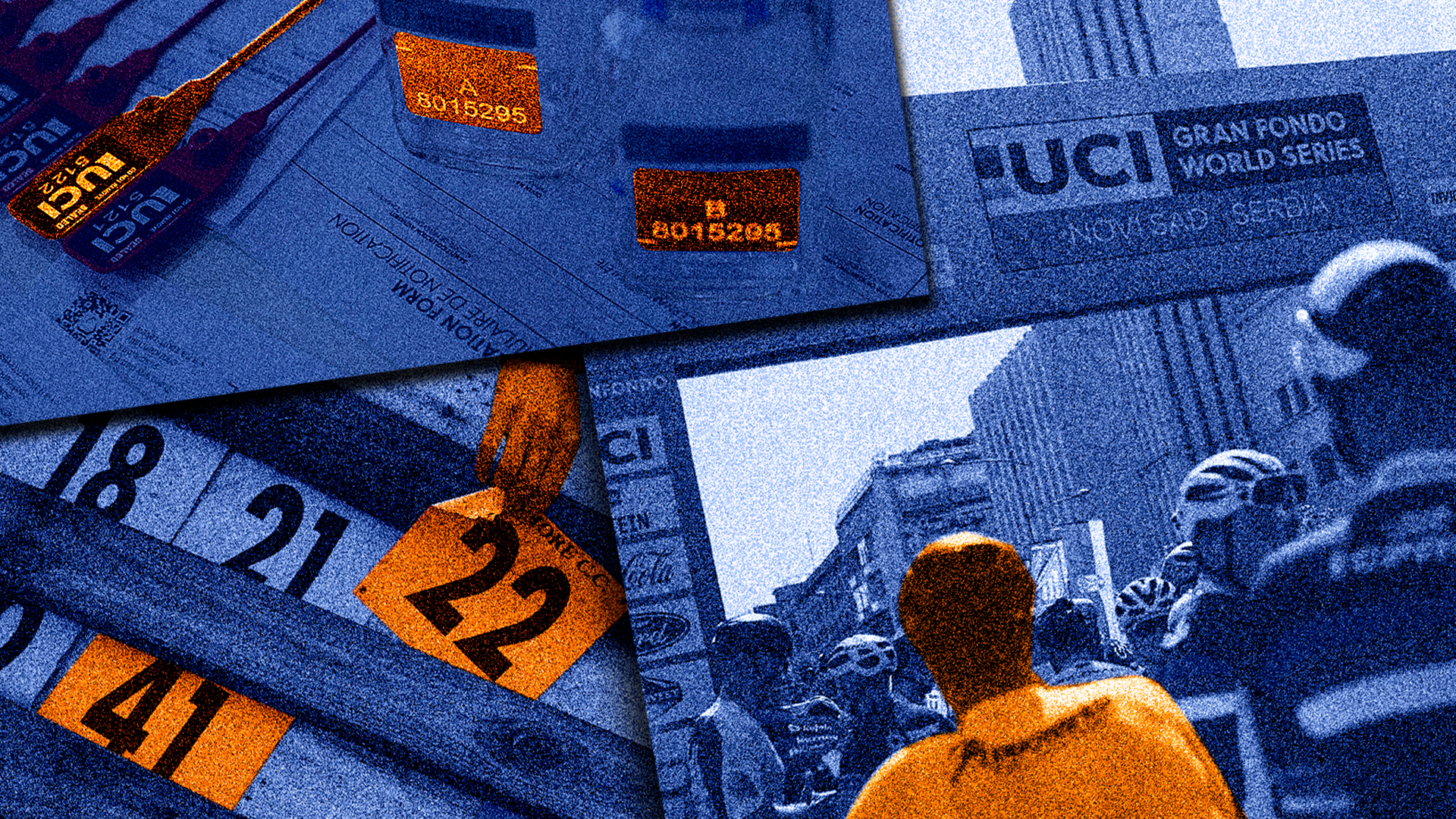

'It’s a wild west of doping activity' - How cycling's amateur scene has become the epicentre for doping

With thousands of riders and very few tests, the amateur cycling scene has become a haven for those willing to cheat to win, where ego is the ultimate prize

Gran Fondos: you’ve possibly raced one, and almost certainly heard of them. Big events, essentially timed sportives, that take place most weekends across Europe, and increasingly more so across the rest of the world. The biggest ones bring thousands of riders together, and can generate significant revenues for organisers. It’s little wonder that each year there are more of them, and that the UCI have jumped on the bandwagon – the sport’s world governing body now has a successful Gran Fondo World Series of 25-35 qualifier events that culminate in the UCI Gran Fondo World Championships.

Just one problem: doping. And a lot of it. Second problem: almost all of it goes undetected.

While professional cycling appears to have a grip on doping, with the number of positive tests among UCI-registered riders hovering around the 15-25 range for most of the past decade, doping cases at age-category amateur levels are becoming more and more prevalent.

Just this summer alone there has been a spate of athletes, many of them successful on the amateur scene, who have been charged with anti-doping violations and been provisionally suspended: French rider Stephane Cognet, who won the 2024 edition of the Fausto Coppi Gran Fondo, tested positive for the steroid Betamethasone; an Italian Masters champion returned a positive test for seven banned drugs, as did another Masters winner for EPO; and one other Italian rider who finished second at the Gran Fondo Sestriere Colle delle Finestre failed to provide an anti-doping sample.

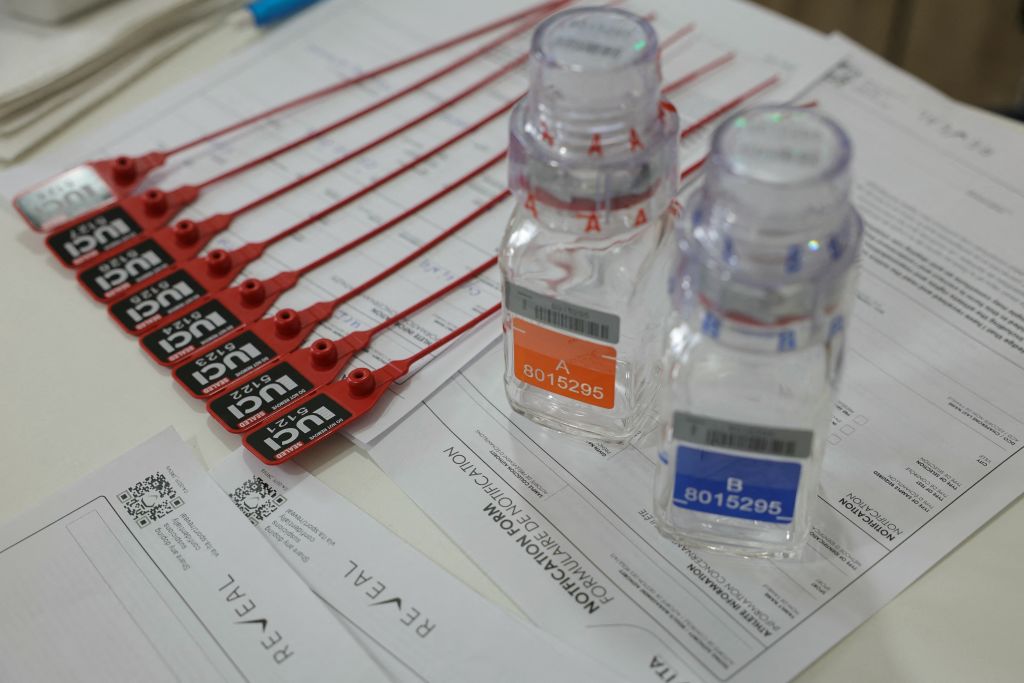

But with the costs of tests north of €1,000, and no mandatory testing place other than at the aforementioned UCI Gran Fondo World Championships, few organisers have the desire to invest significant sums into their events to deter the cheaters. It has led to a situation where, according to one Gran Fondo organiser in Italy, “every weekend we just know that there are people on the start grid of these events who are doping. We just know it.”

What, if anything, can be done about it?

Reward often outweighs the risks

According to the website CycloWorld, which tracks mass participation events across the world, there were over 700 road bike Gran Fondos slated to take place in 2025. Of those, France (116), Italy (96), the United States (93), and Spain (82) lead the way. An estimated 444 of those events – or 62.5% – were in Europe, where world-famous events like the Marmotte, Maratona, Mallorca 312 and Quebrantahuesos are held.

Major race organisers have stepped into the landscape in recent years, too, with the Tour de France promoters ASO now running in excess of 30 events across the globe as part of their L’Étape Series. Gran Fondos linked to races like the Tour of Flanders and Strade Bianche are also big revenue drivers, and have been singled out by the sport’s powerbrokers as essential to the sport’s economy in future years.

In almost all Gran Fondo events, riders are given an overall time and an age group time, with riders finishing in the top three in each category presented on the podium afterwards. In most events, however, prize money is limited – if it even exists. There are some exceptions, though, such as the Levi’s Gran Fondo in the United States that had a total prize pot of $156,000 USD this year, and the Gran Fondo World Tour that had a payout of $36,000 USD until it stopped financially rewarding competitors in 2020. Most incredible is the Abu Dhabi Gran Fondo in the UAE that has a prize purse of AED 2 million, roughly €465,000 – that’s five times more than the prize money on offer at the men’s Paris-Roubaix.

'It's a wild west'

There appears to be an omertà in place when it comes to doping within Gran Fondo racing. Cyclingnews contacted multiple male and female athletes who have finished on the podium of UCI Gran Fondo World Series events in the past two years to discuss the presence of doping, but no one wanted to speak.

John Woodson has been writing about amateur doping for Gran Fondo Daily since 2019. He started to do so after he participated in the UCI Gran Fondo World Championships in 2018, where Spanish rider Raúl Portillo, who won two gold medals at the event, tested positive for doping. “It piqued my interest as to how prevalent it is, and the more I dug into it, the more I realised that amateur doping is this dirty little secret behind the scenes that has been happening all along but is barely communicated,” Woodson said. “You get into the age category events, Masters and Gran Fondos, and it’s a wild west of doping activity.”

Through his years of reporting and research, Woodson has established that three categories of performance-enhancing drugs are most common among amateur athletes: EPO and human growth hormones; testosterone; and contaminated supplements, such as dietary medication and off-label products. “Some of them are taking medication which they’re unaware might contain products that are on the prohibited list,” Woodson said. EPO and testosterone, however, is not a mistake – that is blatant and knowing cheating. “Cases of EPO have been increasing as it’s easily available – there’s definitely a trend of people gravitating towards that,” Woodson added.

Gran Fondos attract riders of all demographics, with age categories starting at 19-34, and then going up every five years. Sources who Cyclingnews spoke to all said that the majority of people who dope are aged between 40 and 60. In 2024, Woodson spoke with an Italian amateur rider who was banned for failing an anti-doping test. Asked how he obtained the prohibited products, the rider – who wished to remain anonymous – said: “I would prefer not to answer how I found the products. [But] not from people in the [cycling] group, even if at the time it was not difficult to find [products] in the group.” The rider’s words speak of a doping epidemic in the amateur ranks.

Cyclingnews contacted both the UCI and the International Testing Agency for this article to gauge how concerned they are about amateur doping and what they’re doing to combat the problem, but both organisations referred the request to the other. “We focus on international-level cyclists,” the ITA said.

It therefore falls to the national anti-doping federations (NADAs) to administer and process tests of amateur athletes in their own countries. But with NADAs being poorly funded – UK Anti-doping (UKAD) recorded a total expenditure of £11.7m in 2023-24 – and the priority being on testing professional athletes, most amateur riders know that the chances of evading detection for doping are high. “It’s like whack-a-mole,” Woodson said. “Think about how many amateur events there are, and each one has thousands of riders. It’s simply impossible for NADAs to get around and test even every winner of each category.”

Allegations of technological fraud – or motor doping – have also surfaced in the past decade. In 2022, the winner of the Maratona, Stefano Stagni, was accused of having a concealed motor, something he denied. But Italian newspaper Corriera Della Sera went in hard. “Stagni had a motor in his bike and cheated… the climbing times on the great Dolomite passes are surreal,” they wrote. Stagni refuted the accusation.

One person with extensive insider knowledge of motor doping told Cyclingnews: “It’s common, it’s everywhere. There is a lot of money in Gran Fondo racing, and people are happy to pay €5,000 to €10,000 for a motor or some assistance. The producers have a lot of clients riding these events.”

The level at some of these Gran Fondo events is high – it’s not uncommon for the average speed of the winners to be similar to what would be expected in WorldTour racing. The top 10% are all fit athletes, many of whom have previously competed in Continental or even professional teams. Knowing that the standard is high is one incentive to dope for some.

“Riders treat each Gran Fondo like a World Championships – they’re all out to compete,” Woodson said. “For whatever reason, they have this overarching need to win, even if there is no money involved. It’s not like a pro whose career depends on results – it’s purely for their ego. And in Italy especially, you’re presented on the podium, with podium girls hugging you, flowers, and then your picture is in the paper the next day. You’d think it was a World Tour-level race.”

Separating competitiveness from cheating

Marco Pavarini is the organiser of the L’Étape Parma Gran Fondo, which takes place in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy in May. He concurs with Woodson. “I was hopeful that after Covid, people’s competitiveness would have decreased, and for a few years this did happen, but now the level of competitiveness among amateurs is very, very high," Pavarini said. “And this is a problem for us because we know there are a lot of athletes pushing their limits, doping, using too many supplements.” Pavarini and his team trialled a new approach at the 2025 event to encourage less aggressive racing. “We didn’t have a starting grid based on a rider’s previous ranking, and we only took times on the climbs, not for the whole course,” he said.

Italy has one of the largest numbers of confirmed cases of amateur doping, but that is largely because it’s one of the few countries that takes the issue seriously. Indeed, wrote the Movement for Credible Cycling in September 2024, “Italy’s standing deserves particular attention… its amateur circuit raises questions since, according to the Italian Federation, more than 700 people (amateur and professional athletes, club officials) are serving [doping - ed] suspensions, from Gran Fondos to professional UCI events and local road races.”

In a bid to clamp down on dopers and to deter them, the Federazione Ciclistica Italiana – or the Italian Cycling Federation – have instructed all Gran Fondos that want support from them that they have to insert a clause in the subscription that states any rider who is caught doping within six months of the event could be fined up to €50,000 for the damage done to the brand. Most Italian events now test up to 10 athletes on event day.

“We need to have these rules and penalties to give the message clearly that doping is a big problem and isn’t tolerated,” Pavarini said. “You cannot delete the past if your event is associated with doping. And events lose sponsors because companies don’t want to be linked with these kinds of athletes.”

Pavarini believes – and certainly hopes – that the deterrent is working. “You agree to the rule when you sign up, and if there’s evidence that you doped, it is simple: we write you a legal letter and ask you to pay this amount for the damage you have done to our brand awareness. Afterwards, there is a judge who makes the final decision.”

Cyclingnews reached out to the Federazione Ciclistica Italiana to confirm if any Gran Fondos have ever taken action against riders suspended for doping, but did not receive a response in time for publication.

Fighting a battle that's already lost?

Deterrence might not be enough, however. And neither is the reality of so little prize money being up for grabs. The simple truth is that there are a lot of highly competitive amateur cyclists who are prepared to go to extremes to reach their own personal goals. They are not ashamed to dope and show no remorse if caught. When they also know that most NADAs won’t even bother sending anti-doping testers to events, many understandably presume that they’ll never get caught.

The unidentified rider whom Woodson interviewed spoke about how “I want to race again because I am a masochist. I love competing.” And one race organiser told Cyclingnews that even banned athletes find a way around the rules. “They participate in races with other federations, or even turn up with their own electronic chip. They don’t want to stop racing.”

Unless significant funds are invested into stopping doping in amateur races – and the UCI nor national governing bodies, with the exception of Italy’s, have shown any desire to do so – then the omertà will persist: doping in amateur cycling will remain an unspoken epidemic.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.