Build it and they will come - How China's high-end bike brands are taking over the US market

Carbon bikes made in the factories that produce major brand names, groupset disruptors like L-Twoo, and a different world of labour and material are preparing to transform the bike market

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The North American bicycle industry has long relied on Chinese OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers) to build frames and other components. The formula was simple: Brand X designs a frame, sends the design to OEM Y abroad, where the frames can be built quickly and cheaply, and manufacturer Y sends those frames and components to Brand X to be marketed and sold to the North American ridership.

In this overly simplistic explanation, this symbiotic relationship has worked perfectly well for decades. In that time, Chinese OEMs have gotten better and better at creating not only inexpensive finished products, but also exceptionally well-built frames, wheels, and other components. In today’s North American market, where at-home manufacturing is often cost-prohibitive or not possible at all due to a lack of equipment and trained craftsmen, the Chinese OEM has provided manufacturing stability.

That’s all changing on both sides of the Pacific Ocean. In North America, manufacturing capabilities have been dropping for decades. Yet a similar reckoning is happening in China, where rising wages and operating costs have led to an exodus to other Southeast Asian countries. Chinese OEMs that remain find themselves needing to adapt to survive.

It’s now, at the confluence of historical trends of Chinese imports dominating the US market, and modern developments like direct-to-consumer sales and AI marketing, that the timing has become almost perfect for Chinese OEMs to take the North American market by storm.

For the future of bicycles in North America, that means more competition in a shrinking market, lower prices for consumers, and better selection. But it all hinges on how Chinese OEMs handle parts of the bicycle business it long had the luxury to ignore.

What is an OEM?

OEM stands for ‘Original Equipment Manufacturer.’ Basically, OEMs are the companies that make the stuff we buy. They partner with brands you know and love, and those familiar brands partner with OEMs to create the products they’ve dreamed up.

These OEMs tend to operate behind the curtain, with unglamorous names you’ve likely never heard of, as highlighted in our recent investigation into where bikes are made. However, the bike industry does have one OEM you’re definitely familiar with: Giant Bicycles.

While Giant produces its own bicycles and components under its business name, it also manufactures bicycle frames, wheels, and other components for other bicycle brands. Giant’s Taichung, Taiwan factory has produced frames for the likes of Schwinn and Trek, among many others. Some of these partnerships date back to the 1970s.

So, while Far East OEMs entering the North American market is a current trend with real tailwinds, it’s not a new phenomenon. Rob Gitelis, founder of Factor Bikes, started as an OEM in Taiwan before launching his own consumer-facing brand.

His factory built bikes for brands like Cervélo, Santa Cruz, Pivot, BH, Focus, and Storck, as well as components for Enve and Bontrager, among others. It should come as no surprise that Factor Bikes are built in Factor’s own in-house production facility in Taiwan.

But many North American bicycle brands still get their frames made from OEMs abroad. The level of control the brand has over quality control standards can vary, but the designs almost always start with the brand, get passed to the OEM for manufacturing, and result in a finished product that’s shipped to North America. Around 12.5 million bicycles are sold in the United States annually, and right around 90% of them come from Asian countries.

Why China?

China is uniquely poised to make a dent in the North American market for several reasons. For starters, China’s economic tailwinds, specifically in the bike industry, make it primed for expansion. China is currently the biggest exporter of bicycles in the world, which means the manufacturing infrastructure is robust, well-established, and in large swaths of the world, well-trusted not only by brands but also consumers.

In fact, estimates indicate that around 60% of all bikes are made in China. This massive market share is bolstered by the immense growth of cycling in China. But more importantly for global markets, Chinese OEMs can hire from a labour force that prizes long hours and a culturally normalised desire to get ahead. That, combined with existing manufacturing infrastructure that doesn’t require any additional up-front investment to get running, makes China a powerhouse.

"The amount of money, let alone hundreds of employees needed with decades of experience each to set up a carbon facility in the US is such an insurmountable task, and we would need to buy equipment from Asia for the factory, and raw material from Japan to use, all of which are subject to tariffs," says Revel Bikes founder Adam Miller. Revel has its bikes built in Taiwan, though Miller also opened a Revel office near the manufacturing facility to ensure close collaboration and to maintain the best quality for his bikes possible. He knows he’ll get a high-quality product at a better price in the Taiwanese factory. It’s money well spent, he says.

"Our expertise is in designing frames and providing excellent customer service, not in developing a carbon bike factory, so it doesn’t make sense for us to focus resources on this."

So the cost to start up a manufacturing facility poses an immediate cost barrier for brands, particularly small and medium-sized brands already struggling with narrow margins and a shrinking market. And the workforce that keeps those factories running also makes overseas manufacturing attractive for North American brands.

While China has developed laws intended to protect workers and has largely eliminated or significantly reduced sweatshop conditions, Chinese worker culture still values long hours and hustle. In fact, among some subsets of the working population, overwork is a point of pride. The 996 trend, for example, has become ubiquitous among Chinese workers: work from 9am to 9pm, 6 days a week.

Gitelis says that it comes down to honour and pride, but also over time. "The Chinese have just as many unions and rights as any other country, and it’s been that way for some time now," he says. "It’s no longer a low-cost workforce. The difference is the amount of hours people are willing to work in China. 10 hours a day is completely normal, and they want that. They’re getting overtime. And if you don’t offer it, it’s actually difficult to hire. People are working really hard to get ahead."

Why now?

The North American bicycle market has been on the decline in the US, and that slide is predicted to continue for the next few years. That spells opportunity for Chinese OEMs, but those Chinese companies are facing challenges of their own, necessitating a pivot not only in business structure but also market focus.

The soft bicycle market requires brands in the North American market to pull back on production in anticipation of lower sales numbers. Margins, too, will take a blow. Yet OEMs control their own production and can adjust to changing sales trends more quickly. Controlling the manufacturing process comes with a ton of benefits, in other words.

Yet labour costs in China have also risen in recent years, so it’s no longer the source of exceedingly cheap labour it used to be. Capricious hiring practices have also led to lots of offshoots from existing OEMs, many of whom have taken their acquired skills and knowledge to other countries in Southeast Asia.

"In many ways, I don’t see these OEMs differently than what we did," says Factor’s Gitelis "What’s driving it, though, is that most of the industry has moved out of China. Most high-end road bike manufacturing has moved to Southeast Asia. China got too expensive. So Chinese OEM factories were left behind, and it then makes sense that they launch their own brand. They see what XDS is doing, and the boom in China, so they created brands first for the big market in China. From there, why not try to export it?"

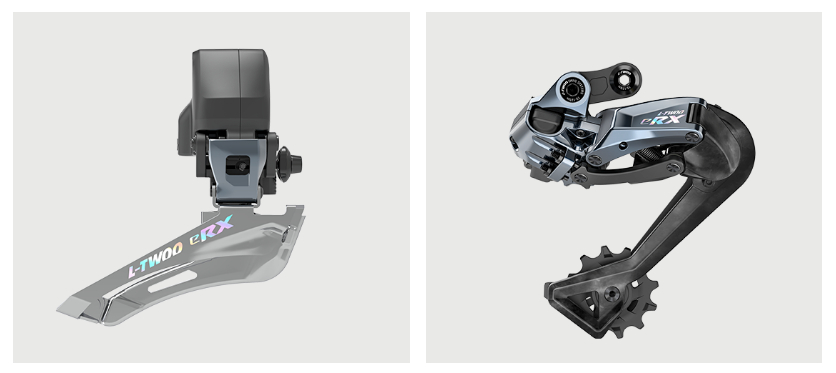

XDS, as Gitelis mentions, has already made its play for North American market share. A direct-to-consumer sales model combined with a low-cost, high-end product to upend what North American consumers consider the entry point for a performance bicycle. It's AD300 road bike, for example, features a carbon frame and fork, internal routing, and L-Twoo components, all for less than $1,300. That’s less than half the price of high-end frames from other well-known brands.

It’s worth noting that L-Twoo doesn’t have the cache in North America that SRAM or Shimano does. But L-Twoo and other brands like Microshift have begun not only to invest in the quality of their products, but also in the marketing of those products. And that’s a key factor Chinese OEMs will need to take into account. High-end customers often simply don’t trust names they don’t recognise.

The quality conundrum

On the one hand, it’s fortuitous for Chinese OEMs that the soft North American market gives them an opportunity to funnel their lower-cost products toward consumers in need of a price break. On the other hand, China’s own reputation works against it.

Fire up AliBaba or Ali Express and you’ll find all the carbon components you can get your hands on, all at cutthroat prices. They could be high-end bits with no branding, or no-name carbon with questionable origins. And that’s the problem: these products have streamed into North America for years, with little or no way to discern the good stuff from the outright dangerous stuff.

"This has been going on for a few years as OEM factories, especially lower quality ones, sold carbon frames directly on Alibaba and AliExpress," says Revel’s Miller. "However, over the last few years, it seems more factories are supplementing their business by selling directly to consumers, because they see the benefits of higher margins with a fully vertically integrated company."

The high-end bicycle customer wants to know that they’re buying the best. Sure, they’re willing to take some risks, but when it comes to travelling at 40mph down a mountain on carbon rims, the high-end bike customer likely prefers to know the wheel will remain a wheel even if it hits a seam in the road.

The Alibaba paradigm has given Chinese OEMs the indication that they can sell products at high volume in the North American market. But, as Factor’s Gitelis notes, building is the easy part. Selling to high-end consumers is more complex. And the high-volume, high-profit margin model may not benefit them in the high-end North American market.

"The sales channels and marketing is equally hard," Gitelis says. “It’s a whole recipe of things” that OEMs didn’t have to focus on when partnering with brands rather than operating as one themselves. For example, high-end bicycle brands often invest heavily in R&D to develop the best products possible. Since the differences between high-end bikes can often be very marginal, it’s important to create the very best design.

And once that design is in place, brands often hire extensive marketing departments to ensure customers understand what those benefits are. R&D and marketing have both largely been absent from OEM operations, but if those OEMs want to compete for North American dollars, they are costs they will have to take on.

Gitelis also notes that the business goals and operations between established North American brands and Chinese OEMs hoping to crack the market differ in significant ways.

"What scares me about these brands is that they have a different mindset on what is an acceptable profit," he says. "They don’t necessarily follow all the rules. For example, I would have 50 licensed seats for a design software, and they would have none.

"I would have to compete for that, and factor my costs into a request for quotes [from prospective customers]. I wouldn’t get that contract because this other company that had all pirated software and no product liability insurance had cut costs and didn’t have to factor them into the quotes."

All of these new costs add up. Depending on how much margin the OEM needs to survive, these costs may become just as problematic as any other brand’s costs, essentially reducing or negating a true advantage in the market.

Did North American brands drop the ball?

It’s tempting to cast blame on North American brands for China’s rise in the market. And in some sense, North American brands did miss opportunities to insulate themselves from such market incursions. But these North American brands also face significant challenges that prevent them from protecting themselves from external markets. In short, North America — and the United States in particular — simply does not have the infrastructure in place to compete with Chinese manufacturing.

American manufacturing in every sector has been declining for decades, as offshoring became more feasible and ultimately cheaper than manufacturing in-house. Consequently, all that manufacturing infrastructure disappeared. It’s a catchy political message to say the US will bring back its manufacturing capabilities, but the reality is that rebuilding will take years, if not decades. And it will prove exceptionally costly. Meanwhile, Chinese OEMs can take advantage of that very long runway to establish themselves in the North American market with their own brands.

Those macro-scale problems have been countered with some micro solutions. Various North American brands read these tea leaves early and began manufacturing in-house, albeit on smaller scales. Boyd Cycling, for example, manufactures its carbon wheels in-house in Greenville, South Carolina. Enve Composites builds some of its high-end frames and components in its Ogden, Utah, facility. And Argonaut Cycles, a small, boutique cycling brand, hand-builds its frames in Bend, Oregon.

It’s not cheap to go this route, and most often, the products that come out of these facilities have price tags that reflect those realities. Still, on-site manufacturing offers a brand more control over the manufacturing process and insulates them from international geopolitical turmoil like wars, tariffs, shipping logistics, and even foreign competition.

What does this all mean for North American consumers?

The obvious answer here is lower prices on bikes and components. But that reality may be fleeting, as OEMs entering the North American market learn the true costs of marketing and R&D - two costly business aspects they previously had the luxury to ignore.

"OEM manufacturers haven't historically done a great job creating brands, especially high-end ones," says Gitelis. "I’m cautiously optimistic it’s not a threat to high-end brands like Factor, but other brands in the industry may face the threat."

Gitelis says he thinks it will be a long while before Chinese brands can compete. He says Factor’s engineering gives it a big head start, and focus on customer experience and on-the-ground touchpoints like local bike shops keeps it ahead.

Revel’s Miller agrees. He says he hasn’t seen any real traction that affects Revel’s sales yet, so the brand hasn’t made any adjustments in its business. He says that specialisation, both in terms of creating a product and marketing it - not to mention offering top-notch customer service - still gives them a leg up on any potential market incursions.

"We’re not blind to the idea that many of these OEM factories are rapidly improving and with better global connection and communication, and that this could become more of a real threat in the future," Miller says. "That being said, competition breeds innovation, and at the end of the day, more people making great bikes at better prices is better for customers riding bikes, and that’s better for all of us who are in the business of bikes, as long as we’re willing to embrace change and adapt."

Dan Cavallari has been writing, photographing, podcasting, and hosting videos about cycling for over a decade. He is the former technical editor for VeloNews Magazine, and contributor to countless titles worldwide, both in and out of the bicycle industry. His recent work has focused on renewable energy and its impact on the future of our world. He lives outside of Denver, Colorado.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.