'Small percentages can make a huge difference' - What's the science behind cycling's long-range attacks?

From Tadej Pogačar’s long-range raids to Ben Healy’s solo masterclasses, the modern breakaway is undergoing a rapid transformation as more riders successfully go it alone

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

At the 2025 European Road Championships, Tadej Pogačar launched a blistering attack 75km from the finish line and won gold. The Slovenian had already established his Thomas De Gendt-like breakaway prowess at the 2024 World Championships with an attack from 51km out, 48km at last season's Il Lombardia and, of course, his 81km solo spectacular at the 2024 edition of Strade Bianche. Pogačar is the greatest rider of a generation – if not the greatest of all time – so arguably his successful long-range attacks are no surprise.

But he’s not the only one catapulting out of the peloton's grasp and staying free. Alessandro Covi at the 2022 Giro d'Italia, Bob Jungels at the 2022 Tour de France and Ben Healy at the 2023 Giro are just some examples of 50km+ solo attacks. In fact, Healy’s carving out a reputation as a breakaway expert, topping his Giro success with a stage victory at the 2025 Tour de France off the back of a 42km solo effort.

It appears that the dogmatic days of sprint trains have been derailed by the lone assassin. But why? What’s behind these successful breaks? Cyclingnews investigates, beginning with insight from a man Healy knows only too well.

Experienced input

Charly Wegelius is the head sports director at Healy’s team EF Education-EasyPost. The 47-year-old, who was born in Finland but grew up in York, raced professionally between 2000 and 2011. He then followed the oft-trodden path to directeur sportif at Garmin Sharp, taking up the role in 2012. He’s been with the American team ever since. Wegelius has racked up the miles and seen the sport evolve, so we thought he’d be the perfect sounding board to project our breakaway theories.

Firstly, Charly, how much of today’s success rate comes down to improved pacing via power data? "Riders have had power meters before racing styles changed, so that’s a misnomer. Clearly, riders have a good idea now of what a sustainable pace is over a long period of time. However, it still takes skill to manage your pace over changing terrain. It’s not as simple as punching in the average power and keeping that up; you have to know when to push and when to recover." So, that’s a no.

What about race radios and real-time feedback? Has that altered the psychology of both attackers and chasers in long-range moves? "Race radios have been around for over 20 years, so again I think it’s misleading to say that they’ve had a big effect on racing style. When experiments have been made with radio bans, I’d argue that the racing is more negative and in favour of the peloton, as the chasing riders push harder in the absence of information for fear of coming up short." Another no.

What about modern course designs? Are punchier finales, more technical terrain and fewer pure sprint stages encouraging earlier attacks? "It’s always helpful if an organiser positions a well-placed climb that’ll force a chasing peloton to slow down, either to avoid dropping sprinters, or to preserve resources for later." Hmmm, we'll mark that as a maybe then.

Okay, let’s go broad. Are long-range attacks succeeding because riders are stronger? "The general athletic level of riders is higher than it’s ever been, but importantly, an individual rider is more aerodynamic and better fuelled than in the past. This makes high speeds over long periods more sustainable than in the past. This goes some way to shrinking the gap between peloton and breakaway rider that in previous years gave the peloton an overwhelming advantage." Bingo.

It seems that aerodynamics has a key role to play, plus the facet of performance that’s dominated recent times – fuelling. With that in mind, let’s get streamlined and break away to the world of applied academia.

The CFD magician

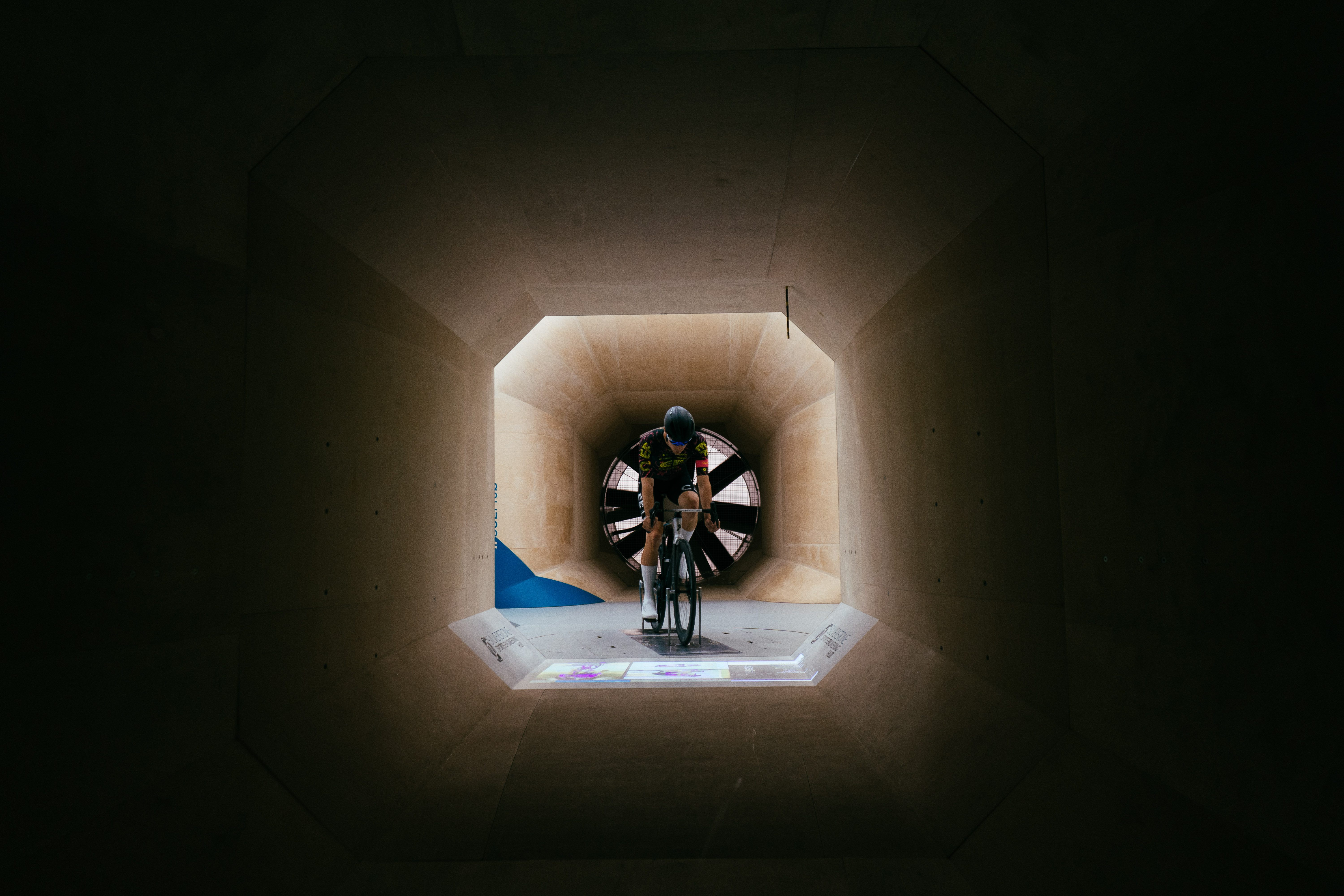

Bert Blocken is a professor of mechanical engineering at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, Scotland, who specialises in aerodynamics. You might never have heard of the Belgian, but WorldTour performance engineers and sports scientists widely use his cycling-specific findings. He’s a master of computational fluid dynamics (CFD), making him a man in high-performance demand. There’s little Blocken doesn’t know about slashing drag, optimising rider positioning and forging energy savings. So, what does Blocken feel about aerodynamics proving the driving factor behind solo success?

"It adds up because the mathematics adds up. Let me explain why," he says. "Around 90% of the total resistance faced by a breakaway rider stems from air resistance, whereas behind, if the riders are pedalling in a paceline [straight line], that drops to around 50 to 55%.

"Now, say the modern-day rider is reducing air resistance by 3% via cutting-edge skinsuits, better helmets and so on. Bear in mind that 3% figure is from the wind tunnel, which is around 100% air resistance. So, in the real world and applying the 90% air resistance battled by the breakaway rider, the aerodynamic benefit of all of the gear is around 2.7% [90% of that 3% figure]."

"Now, let’s say the rider who’s leading the chase behind will be facing around 76.5% of resistance from the air. They’ll be enjoying a lower aerodynamic benefit from the gear, more specifically 2.295% savings [or 76.5% of 3%] or a 0.405% difference."

We’ll stop Bert in his tracks, as you might think that the lead chaser will be facing the same 90% air resistance as the breakaway rider. That’s logical, but discounted by previous research by Blocken all the way back in 2012. He read articles on rally driving, which showed that if the second car is very close behind the first one, the lead car has a lower fuel consumption.

His studies then revealed that yes, the rider upfront also enjoys the benefits of slipstreaming. This happens because the following rider fills the turbulent wake behind the rear wheel, smoothing airflow and reducing drag. Back to Blocken…

"Another example… If a rider’s right in the belly of the peloton, our modelling shows they might be riding along at 20% of the main rider. That adds up, as Peter Sagan always said he’d position himself behind so many riders that he didn’t need to pedal – it just sucked him along. Anyway, with 20% air resistance, the aerodynamic benefits from the gear will result in a slender drop from 3% to 2.43%."

In short, because the chasers are facing reduced air resistance, the impact of aerodynamic gear is proportionally less. "That benefit is simply much more significant when riding alone than in a group," Blocken adds. "Every aerodynamic improvement always benefits the one that’s suffering the most."

Which is why a further aerodynamic nudge should, in theory, see even more victorious breakaways. Say the aerodynamic improvement is 5%, not 3%. That’d mean a 0.675% advantage over the lead chaser compared to the 0.405% seen before.

"Of course, you might say these figures aren’t much, but we know how small percentages can make a huge difference," says Blocken. "That’s especially true if these small figures are applied over a breakaway distance of 50km or more."

Chasing formation

So, the modern-day solo artist has an advantage over historic breakaway warriors like Jens Voigt. Which begs a further question: does Blocken have any advice for those chasing the likes of Pogacar and Healy?

"It’s actually something we modelled last year," says Blocken. "In general – and in the absence of crosswinds – the chasers form a straight paceline. But I found no published study that this was the most proficient formation. My colleagues and I ran CFD simulations of 276 formations of three, four and five cyclists, including validation with wind-tunnel measurements.

"The results showed that for a three-person group, an inverted triangle formation provided a drag reduction for the protected rider [before the trio rotated] down to 39%, compared to a single rider. However, this came at the expense of increased drag for the leading riders. For four-rider groups, a diamond formation most substantially shields the ‘protected’ rider, with a drag reduction down to 38%. Interestingly, in this formation, all riders register a drag below that of a single rider and even below that of the leading rider in a four-cyclist single paceline."

Finally, for five-cyclist chase packs, a two-by-two formation in front of the ‘protected’ rider reduces drag to 24%, which is 20% below the best position in the single paceline.

Whether these various chase formations play out in the dynamic world of racing remains to be seen, but it’d certainly be feasible if the chasers were from the same squad, rotating at regular intervals.

Fatigue-busting fuelling

Wegelius also mentioned the impact of nutrition, which we’ve heavily covered before, specifically high-carbohydrate feeding, which is one mooted reason behind the increasing speeds of the peloton.

But broadly and briefly, elite riders are consuming more on-the-bike carbohydrates than in years gone by without suffering gastric repercussions. "Five years ago, after long races, I’d always end up running to the bathroom. Now, I can consume up to 120g of carbohydrates per hour without any issues," Pogačar revealed after his Giro-Tour double of 2024. "Before the race, we make a food plan, looking at the stages and then seeing the race hour by hour. I then know what I want to eat every hour. And make sure I get those 100g of carbohydrates every hour."

This higher feeding is arguably more about fatigue resistance than boosting speed, which is a boon in a breakaway. Just note before you start mimicking the professionals that the power outputs of elites, which can be 300-plus watts for several hours at a time, mean a massive energy output.

That means burning through 300g-plus of carbohydrates per hour, so even when they become more proficient at burning those carbohydrates, there’s still a deficit, meaning relatively the amounts they’re consuming aren’t huge. The average amateur will not be burning that many carbohydrates, so they don’t require so much on-the-bike food. We’ll leave the impact of nutrition there, as Blocken has a further theory behind the breakaway kings and queens.

Model behaviour

"Another reason I suspect breakaways are proving more successful is due to performance modelling," he says. "There have been several papers looking into this, which attentive teams like Ineos Grenadiers and Red Bull-Bora-Hansgrohe will no doubt have taken note of. My colleagues had a paper of theirs published on this very subject."

Blocken’s colleagues concluded that the most effective breakaways are launched when a rider can sustain a higher speed than the peloton for the longest possible time. According to the model, the sweet spot is just before speeds are naturally reduced for an extended period, most notably at the foot of a long climb.

Climbing sections are particularly fertile ground for attackers. With speeds lower uphill, the aerodynamic advantage enjoyed by the peloton is reduced, making it harder for the bunch to use drafting to reel in a lone rider. As a result, breakaways launched on climbs are far more likely to establish a meaningful gap.

Timing, however, is crucial. If a major climb appears too early in the race, the peloton may still have the collective strength and motivation to close the gap later on. That said, the research shows that an early attack can still be optimal if the climb is sufficiently steep or long.

The study also highlights the importance of limiting the time spent travelling slower than the peloton. Whenever a breakaway rider’s speed drops below that of the bunch, the advantage rapidly erodes. For long climbs or those followed by fast descents, it may therefore be more effective to attack partway up the ascent, allowing the breakaway hero to sustain their effort all the way to the summit.

The researchers say their framework opens the door to more advanced modelling, incorporating individual rider fitness, training status, nutrition, and even multi-rider breakaways. As teams employ greater numbers of data scientists and performance engineers, breakaway modelling will inevitably become more refined and more specific. And, says Blocken, in the future that could mean customised skinsuits.

A suit for every occasion

"Skinsuits are essentially developed for a rider riding alone in a wind tunnel," he says. "They aren’t optimised for the riders in the peloton where, as we’ve seen, the air play is completely different, including lower resistance.

"It’s become public knowledge that you have skinsuits optimised for different maximum speeds, depending on fabric used and seam placement. For instance, I know that skinsuits specifically for sprinters and their final sprint efforts are currently being developed. So, I can totally see skinsuits being developed based on modelling that’ll optimise time and energy savings in the peloton, followed by breaking away at a certain point."

It's a vision down the road, albeit Blocken adds, it could be pretty far down that road, as optimising skinsuit design also ties in with the most awkward impediment to aerodynamics. "Helmets are a nightmare to study on their own, as well as their impact on skinsuit airflow. Those high degrees of rotation make optimising both very tricky."

But not impossible. When it happens, there’ll be even more data-driven moves unleashed by world-class riders like Tadej Pogačar and Ben Healy. Science can’t, and shouldn’t, mask their bravery and resilience. But it’s clear that improved aerodynamics, smarter fuelling and performance modelling are playing an integral role in defeating the chasers. Will the dial shift again? It’s inevitable, says Wegelius. "Nothing is permanent in cycling – change and evolution are a given."

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.