'It's great they remember my father like this' – Vuelta a España pays homage to its first-ever Italian winner, Angelo Conterno, with Grande Partenza in Turin

1956 Vuelta a España winner Conterno key figure in exhibition about Turin's contribution to Spanish Grand Tour

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

When the Vuelta a España announced late last year that it would be having its first-ever start in Italy this summer, only a few fans realised that the chosen city for the Grande Partenza, Turin, was also the birthplace of its first-ever Italian winner, Angelo Conterno.

Only a few fans, that is – barring the cycling tifosi in Turin, who knew full well that back in 1956, Conterno had triumphed overall in the Spanish Grand Tour, the biggest victory of his career, despite suffering a major fever on the last day.

Conterno himself died in 2007, but in the countdown to the Vuelta a España's start on Saturday, the city council organised an exhibition, "Torinesi di Spagna” – Turin-born riders from Spain – to commemorate his victory and the contribution of riders from the north-westerly city and its environs to the Vuelta throughout its 90-year history.

"It makes me very proud that the Vuelta has come all the way from Spain to start here," Marco Conterno – Angelo's son, who still lives near Turin – told Cyclingnews earlier this week.

"It's the Vuelta a España, but bike races are special because they belong to everybody, and a foreign start like this just reflects that even more. That's the beauty of the sport, it's something that everybody can enjoy, because the roads where you spectate are open to everyone.

"Obviously, a start like this is designed to promote tourism. But my father would have been 100 in 2025, and it's nice that even so, what he and others managed to achieve as racers in the Vuelta and other events is still remembered by so many people. And that's also part of the Vuelta start here in Turin."

Conterno's victory in the Vuelta a España came after starting the race as co-leader with fellow-Turin rider Nino Defilippis of the Italian national squad.

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

But then, in keeping with so many Vueltas over the years, one seemingly unimportant first week stage then turns out to be the key to the entire race. In shades of – for example – Sepp Kuss moving up the GC hierarchy on the first summit finish of the 2023 Vuelta before going on to win it, Conterno got in a break on stage 2, winning it and surprisingly took the lead, a lead he'd never relinquish.

"That lead defined the hierarchy of the Italian squad and made him their main GC contender," Marco explains.

"It wasn't decided immediately, and there was some internal rivalry, but it was clear my Dad was in good shape, and he defended the lead he'd got on stage 2 all the way to the end."

However, the Vuelta marked a breakthrough for the rider in his 15-year career, which was not exempt from some controversy, given he was so ill on the last stage he only managed to get over one climb with some assistance – pushes – from his teammates.

The penalty awarded by the judges, a 30-second ban, though, was not enough to deprive Conterno of the overall, by just 13 seconds, over Basque Country cycling star Jesus Loroño. And as Mundo Deportivo, the leading newspaper of the era for reporting on the Vuelta, pointed out in its final article on that Vuelta, the Italians could have criticised that the top Spanish riders had also received "excessively enthusiastic support from the public" - ie, pushes – on the Sollube ascent as well, and for which they did not get any fines or penalties at all.

"The previous night he'd gone down with a fever, shivering and with his temperature all over the place," Marco Conterno recalls, "and even though teams barely had doctors back then, it was clear it was a really bad one.

"He went on, but he was risking his life by doing so, given that he could barely see at some points and was riding like a robot, he was barely conscious and could barely see the others.

"In fact, he said a few years later that with hindsight, if he'd been more conscious of the risks, he'd have abandoned, even though he was on the point of winning. He shouldn't have risked his life like that."

Although in an era when the Vuelta was still without mountain top finishes – something amusing to remember, given its current predilection these days for seemingly going up every summit it can find in Spain – Conterno still faced several climbs on the run-in to Bilbao, Marco says.

"He was a good all-rounder, and if the stage had been flat or less technical on the descents, he might have been ok. But he nearly came a cropper on a central reservation at one point, and rather than risk him going over an edge of a downhill, his teammates opted to help him."

"His sight was so bad, Loroño actually asked him at one point during the stage, 'Can you see ok?' My father hadn't actually realised Loroño was riding in front of him! He was relying on the sound of the wheels just to keep going."

With so much in play, the decision was made to keep going – "winning a Grand Tour isn't easy", as Marco puts it – and gradually the fever lessened and his sight improved. A breakaway with Loroño was brought back, and the Vuelta victory ended up going to Conterno and Italy. That was despite the late time penalty then awarded, and a subsequent visit to the hospital for Conterno for a full check-up.

If Conterno struck lucky in terms of the penalty, he was not averse to his own share of misfortune, too. In 1958, when leading Paris-Roubaix alone and with just 20 kilometres to go, his time gap evaporated when he was forced to stop at a closed level crossing.

Other major achievements by Penne Bianca – white feather, Conterno's nickname, so-called because of a lock of white hair and his comparatively late start to professional racing - included wearing the maglia rosa of the Giro d'Italia for a day in 1952, as well as taking three stage wins. But his outright victory in another Grand Tour remained the one that mattered the most.

A visit to the exhibition

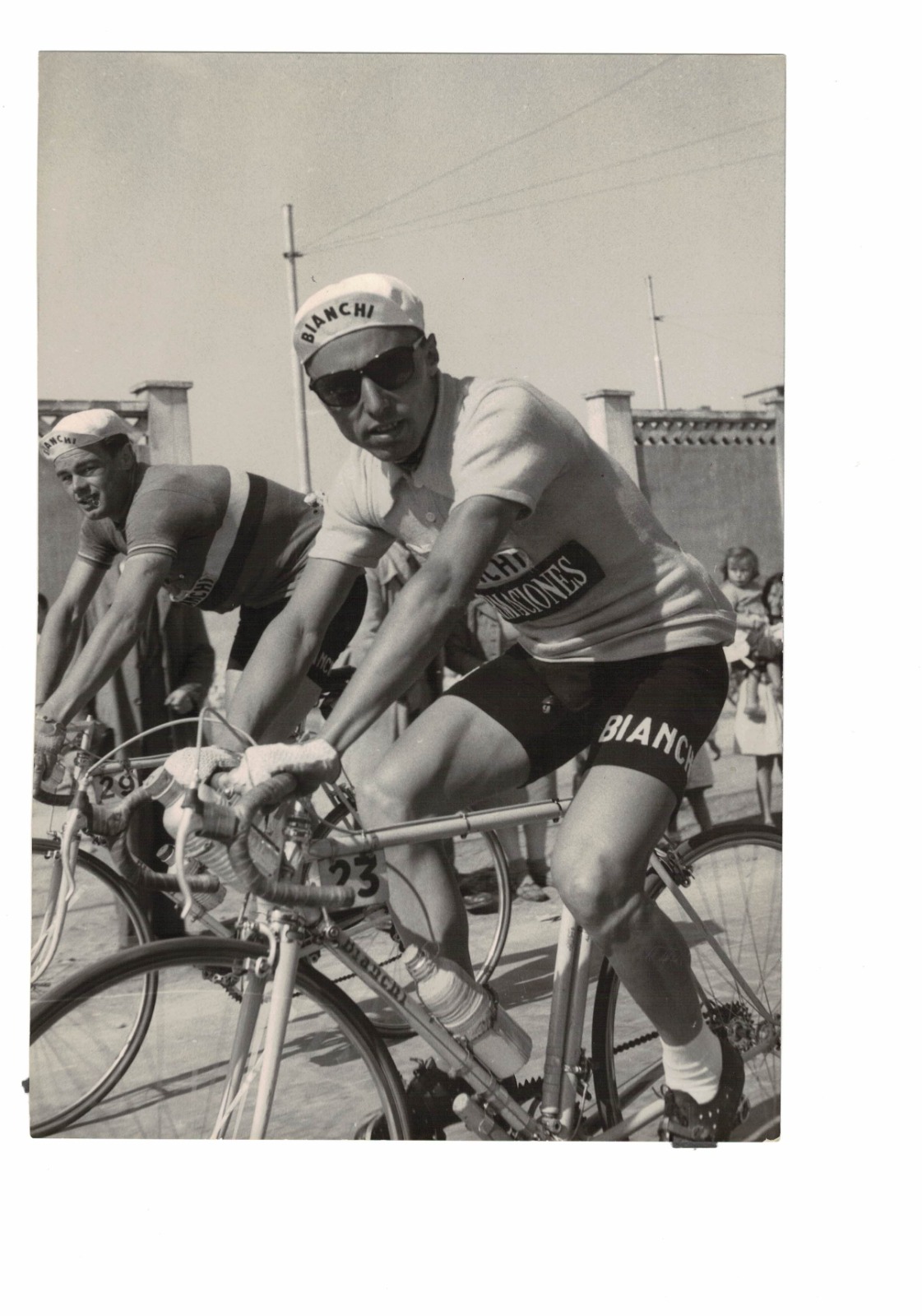

"Come to see the bikes?" the security guard at the front of Turin's biggest public exhibition hall says, "Go right through." Sure enough, in a single, large room behind him, the images on display for the "Torinesi di Spagna” exhibition show what the riders from Turin and its environs have managed to achieve in the Vuelta a España, right from when it started in 1935.

The contrast between the faded black-and-white photos of nearly a century ago with the location – a modern-looking high-rise building on Turin's bustling Corso Inghliterra avenue – could hardly be greater. But there are pictures of Edoardo Molenaar, winner of a stage in its first-ever edition in 1935, as well as its first-ever mountains classification, and of Nino Defilippis, who pulled off the same achievement in 1956, as well as no less than nine stages of the Giro d'Italia and seven in the Tour de France.

Lesser-known figures include Giancarlo Astrua, who also picked up a stage victory in the 1956 Vuelta, but as the photos also show, the achievements of Turin-born riders in the Vuelta extend right through to 2016, when Fabio Felline stood alongside overall winner Nairo Quintana in Madrid as the outright champion of the points competition.

Logically, again, though, Conterno is the star of the show, with enormous images of Spanish newspapers cuttings from the era, like Mundo Deportivo and MARCA, reporting on his success. (British fans in particular may be pleased to note that Mundo Deportivo's final report also singled out international racing pioneer Brian Robinson's eighth place overall, the UK's first ever top ten in a Grand Tour, for praise. "Robinson's success shows we have to count on riders from this country, where just a few years ago they were considered mere tourists in these kinds of stage races. This bodes well for the Tour, if he finally races it as seems likely," the newspaper report said.)

However, the riders from Turin are, logically, the main protagonists, and "The exhibition shows us a specific and very important era of cycling here," Piedmont-born cycling journalist Aldo Peinetti, curator of the exhibition, tells Cyclingnews.

"We knew how important riders from Turin had been on the roads of the Giro d'Italia, but thanks to the Tour visiting here and now the Vuelta, we've been able to put this together too."

"Interestingly, Molenaar was a winner in the Tour de France too, of a very tough stage in 1931, and then went on to succeed in the Vuelta. But it's Conterno who has his high point of his career in the 1956, handling the Vuelta victory with a great deal of consistency, resilience and racecraft, where others like Defilippis also succeed, as well as doing so well in high mountain stages of the Tour. Essentially, in a single year, they were doing brilliantly in all areas of the sport. And that's what the exhibition is all about – focussing on what people have done in the past, particularly in an era where Coppi seemed to overshadow a lot of other riders' achievements, but hopefully acting as an inspiration for now too."

Inside, there are models of Turin-made bikes from the last century, ranging from a Frejus – the same type Gino Bartali won the 1948 Tour de France with – and a 1949 Legnano, the same type that Fausto Coppi also used. Coppi, curiously enough, has limited mentions in the exhibition, even though he was born in Piemonte and is by far the region's most famous rider. However, he only raced the Vuelta once, in 1959, with limited success.

The Vuelta's Grande Partenza in Italy means that together with Utrecht and Liège, Turin is just the third location ever to host starts and/or finishes of all three Grand Tours. But the considerable gap between Defilippis and Felline reveals that the entire region of Piedmont, let alone its capital, Turin, is no longer producing top bike riders with the same frequency as before.

Franco Balmanion, winner of two Giros in the early 1960s and born just northwest of the city in Nole, remains its last Grand Tour champion, while the velodrome on Corso Casale in Turin was renamed after Fausto Coppi but is no longer a cycling venue.

But on the plus side, the Giro has returned to Turin for a Grande Partenza both in 2021 and again in 2024, and Filippo Ganna (Ineos Grenadiers), born in Piedmont, will be one of the stars of the Vuelta this year.

"Turin has got a great tradition of cycling," Peinetti says, "and these investments, like bringing the Vuelta, are part of a campaign for cycling-based tourism, too, so an international audience can see what the whole of Piedmont is like.

"But an exhibition like this with the 1956 Vuelta winners like Conterno isn't just nostalgia for nostalgia's sake – it's also a good way of remembering the founding fathers and its roots, something cycling has always done better than any other sport."

"They were riders who left a mark on the sport," adds Marco Conterno, "and those experiences still matter today."

Subscribe to Cyclingnews for unlimited access to our 2025 Vuelta a España coverage. Our team of journalists are on the ground from the Italian Gran Partida through to Madrid, bringing you breaking news, analysis, and more, from every stage of the Grand Tour as it happens. Find out m

Alasdair Fotheringham has been reporting on cycling since 1991. He has covered every Tour de France since 1992 bar one, as well as numerous other bike races of all shapes and sizes, ranging from the Olympic Games in 2008 to the now sadly defunct Subida a Urkiola hill climb in Spain. As well as working for Cyclingnews, he has also written for The Independent, The Guardian, ProCycling, The Express and Reuters.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.