CIRC: Lance Armstrong's ban holds as McQuaid and Verbruggen fall under scrutiny

Rider shown blatant favouritism and bias by former UCI heads

Lance Armstrong will not see his lifetime ban for doping reduced as a result of the Cycling Independent Reform Commission (CIRC).

UCI to publish CIRC report on Monday

Riis and Vinokourov among 174 people interviewed by CIRC

CIRC: No new doping admissions or proof of corruption in UCI

CIRC finds no proof of UCI corruption but questions linger over governance

CIRC suggests that doping has gone underground with micro-dosing and TUE abuse

The report, published Monday by the UCI, came after the Commission were charged with a mandate to investigate the problems cycling has faced in recent years, especially the allegations that the UCI has been in involved in any wrong doing in the past.

In total the Commission spoke to 174 individuals, including Lance Armstrong. The American had hoped that his cooperation would result in the Commission recommending a reduction in the former athlete’s ban from 2012. However no such suggestion was issued and despite meeting with CIRC on two separate occasions Armstrong remains banned for life.

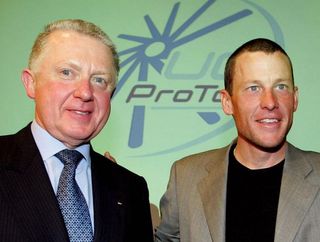

The Commission studied and investigated the relationship between the former rider and the UCI and found several instances in which Armstrong was provided with preferential treatment from former UCI presidents, Hein Verbruggen and Pat McQuaid. The Commission highlighted the rider’s backdated TUE in 1999, the workings of the Vrjman report – of which Armstrong and his representatives played a major role - the two donations Armstrong provided to the UCI totalling $125,000, how the UCI disregarded their own anti-doping testing rules in order to facilitate the rider’s comeback at the 2009 Tour Down Under, and how the UCI fought USADA for jurisdiction in the US Postal case.

The CIRC’s report provides a damning indictment over the UCI’s relationship with Armstrong, painting a picture of incompetence, improper governance and unethical behaviour. However the report stop short of calling the UCI’s behaviour corrupt and states that no positive tests relating to the Tour de Suisse in 2001 were ever covered up.

Perhaps the most pertinent line in regards to Armstrong’s relationship with Verbruggen and Mcquaid reads as follows:

“The UCI leadership did not know how to differentiate between Armstrong the hero, seven-time winner of the Tour, cancer survivor, huge financial and media success and a role model for thousands of fans, from Lance Armstrong the cyclist, a member of the peloton with the same rights and obligations as any other professional cyclist.”

Get The Leadout Newsletter

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

The lifetime ban

The only ray of light for Armstrong in the entire 228-page report comes in the form of an acknowledgement that his lifetime ban may be out of sync with the sanctions handed down to others cheats.

The report reads: “There is inequality also in relation to sanctions. It is true that there is a striking difference when looking at the period of ineligibility of the sanction against Lance Armstrong and certain riders that have testified against him. The range goes from 6 months up to a lifetime ban. CIRC is of the view that this difference in treatment can hardly be justified by looking at the gravity and/or seriousness of the ADRVs in question.275 It appears to the CIRC that the doping practices of Lance Armstrong were not any different to those of many other riders. CIRC has had the opportunity to interview a lot of other riders and team personnel who have confirmed that the peloton was for a long time doping infested and that more or less identical doping practices were adopted throughout the peloton.”

“All of this is of course no excuse or justification for Lance Armstrong’s behaviour and there cannot be a shadow of a doubt that such behaviour warrants a harsh sanction. However, equal treatment is a fundamental principle on which the fight against doping and its acceptance by all stakeholders is based. At the end of the day, the difference in treatment can only be justified by the fact that some of the riders, contrary to others, chose to break the omerta.”

According to USADA, the body that handed Armstrong his lifetime ban, all athletes sanctioned as part of the US Postal investigation were handed the same opportunities to cooperate with their investigation in 2012 – a view not shared by Armstrong, who failed to defend himself against the charges and instead waged war on the US agency and its leader, Travis Tygart.

On the related matter, although without direct causation, the CIRC report adds: “By adopting the WADA Code the anti-doping community has decided, in the CIRC’s view correctly, that the advantages of obtaining information through plea bargaining with athletes must be given priority over the principle of equal treatment of athletes. Of course this entails a great responsibility for ADOs that use this important tool in the fight against doping. They must offer the same opportunity to come forward with valuable information to all athletes alike and adopt similar protocols when it comes to rewarding the athletes with reductions/suspension on sanctions for the information provided.”

With regards to Armstrong’s relationship with the UCI, CIRC highlights the allegations made by Floyd Landis and Tyler Hamilton as particularly important. Both US Postal ex-teammates allege that Armstrong told them of a positive EPO test from the 2001 Tour de Suisse, which, with help from the UCI, was covered up after the rider and the UCI met in Aigle, Switzerland. Landis also testifies as part of his USADA affidavit that Armstrong said he had paid the UCI to hide the positive test.

CIRC also looked into a USD 25,000 payment made by Lance and Kristin Armstrong in letter dated May 2, 2002. In the letter, Armstrong wrote: “I understand that the UCI is currently asking all of the professional trade teams to make a donation in support of further out-of- competition drug testing...In an effort to speed up this process along and to show my commitment to this effort, I enclose my personal donation to the cause in the amount of USD 25,000. Please use these funds in any way you deem appropriate to continue the fight for drug-free sport and to eradicate those who cheat from within our ranks”. Lance Armstrong added: “While we both agree that the underlying science is very encouraging, I am not confident that the test has gone through the rigorous clinical analysis that is necessary to ensure it is 100% accurate...I stand with you in support of more and more out-of-competition testing. And, I stand ready to help in any way I can. I am confident that you will put my donation to furthering our parallel goals”.

Later that month Verbruggen handed the payment to the Council for the Fight Against Doping (CFAD) and the funds were used to help in the testing juniors and under-23 riders.

The UCI cashed the cheque May 28 2002, and Verbruggen replied to Armstrong, stating: “As discussed on the phone, we would like to spend this money in controls of the Juniors and -23 categories. The money will be added to our budget that has been established this year and that is composed of contributions from the UCI (over 50%), share of riders’ prize money, National Federations, teams and organizers. This budget is managed by our CLCD (Conseil de Lutte Contre le Dopage) [Council for the Fight Against Doping]...The CLCD will be informed of your donation and the fact that this 2002 budget increase will be geared towards testing the younger age categories”.

The CIRC report adds that it is not clear if the telephone contact between Armstrong and Verbruggen took place before or after receipt of the cheque by the UCI.

CIRC also confirmed that after Armstrong returned a ‘suspicious’ test for EPO at the 2002 Dauphine the UCI requested that Martial Saugy, Director of the Lausanne laboratory meet with Armstrong. Although such a meeting might be deemed as highly unusual given that it was for Armstrong’s benefit only, the CIRC found that “an independent analysis by the Director of the Montreal Doping Control Laboratory concluded that” it would not “allow him to circumvent the analytical detection procedures for the use of doping substances and EPO in particular.”

The report later adds that instead of target testing Armstrong after his suspicious test readings in 2001 and 2002 – as determined anti-doping body might – the UCI’s response seemed to be one born out of protectionism and favouritism.

From the evidence gathered by CIRC, they conclude that Armstrong did not test positive at the Tour de Suisse in 2001, nor did they evidence that there was “any indication of a financial agreement between Lance Armstrong and Hein Verbruggen or, as would follow from the absence of evidence of a positive test, of any attempts by UCI.” Two of Armstrong's samples were deemed suspicious, but did not meet the threshold of an anti-doping rule violation.

In relation to Hamilton’s and Landis’ sworn testimonies in the USADA report, CIRC found that: “it is unfortunate that such serious accusations can be made public, without UCI first being consulted and the allegations being thoroughly investigated.”

The $100,000 donation

It is well documented that Armstrong made a second donation to the UCI with the sum of $100,000 transferred to the UCI in 2005, the year in which Armstrong won his final Tour de France and retired.

On this matter, the CIRC report found: “On 16 March 2005, an agreement was reached for the purchase of a Sysmex blood testing machine. The invoice for CHF 76,616, not including VAT, for a Sysmex XT-2000i was sent to UCI on 6 July 2005 and paid by the federation on 26 August 2005 from the budget of the SSCC under the heading “funds paid by Lance Armstrong”. The invoice was sent to Lance Armstrong by UCI on 3 November 2005 with a promise to come back with proposals for the remaining USD 38,000.

“After several reminders from UCI on 1 June 2006, 28 December 2006 and 4 January 2007, USD 100,000 was credited to the UCI account from Lance Armstrong's bank account on 5 January 2007. CIRC has not managed to identify proposals made to Lance Armstrong by UCI for the allocation of the remaining USD 38,000, nor has it determined how this money was spent.”

Armstrong was requested to make another donation to the UCI by Verbruggen in April 2008 in order to help finance the Biological Passport. At the time Armstrong had not yet announced his full comeback to the sport and was not yet in the testing pool for athletes. There is no indication within the report as to why Verbruggen – who was no longer the UCI President – thought it necessary for Armstrong to make another $100,000 donation. CIRC add that no evidence of the payment being made or received was found during their investigation.

The Vrijman report

The Vrijman report from 2005 also receives scrutiny from CIRC in relation to how it was set-up, managed and compiled, with several questions stemming from the UCI’s involvement, the lack of independency, and Armstrong controlling aspects of the report itself.

According to CIRC: “Several sources, notably UCI staff and former UCI staff, reported that the UCI leadership had on several occasions “defended” or “protected” Lance Armstrong or taken favourable positions towards Lance Armstrong indicating that he had received preferential treatment. Among the explanations given to the CIRC was the UCI's promotion of a “celebrity rider” after the Festina scandal. The idea was to shine a spotlight on the sport through its best athletes, like the “people’s heroes” such as Lance Armstrong. The Vrijman report was one example of this policy.”

The report, which was leaked before WADA could see it, recommended that Armstrong should be cleared of any suspicion surrounding the retrospective testing of his blood samples from the 1999 Tour de France, where they were claimed by L'Equipe to have contained EPO. It denounced the manner in which the doping laboratory in Châtenay-Malabry carried out its research, as well as questioning the ethics of World Anti-Doping Agency chairman, Dick Pound.

The way in which the report was set up lacked transparency and independence. Armstrong’s manager was allowed to draft the announcement of a report for the UCI’s benefit; the UCI communicated privately with Vrijman in a way that undermined WADA’s position in the matter, and perhaps most damaging of all, CIRC state that “the preliminary report was subsequently revised by Armstrong’s lawyer” with critical inserts relating to WADA added in. The ‘marked up’ version was compiled by Armstrong’s counsel and presented to Verbruggen first. The Dutchman ordered a second version to be written.

CIRC found that there was no evidence that Armstrong himself had financed the report adding that “besides a temporal correlation between the actual payment [$100,000] by Lance Armstrong to UCI in January 2007 in respect of his promise to make a donation to the fight against doping and the discussions between UCI and Scholten/Vrijman on the payment of outstanding fees between December 2006 and July 2007, CIRC has found no relationship between the two financial transactions,” before adding that “notwithstanding the above, once again CIRC notes that UCI did not act prudently in soliciting and accepting donations from an athlete, and all the more so from an athlete in respect of whom there were suspicions of doping.”

The Tour Down Under

While the majority of CIRC’s concerns and investigation into the relationship between Armstrong and the UCI centre around the Verbruggen era of governance, two elements under Mcquaid’s watch also faced scrutiny.

The first surrounds Armstrong’s comeback in 2009 at the Tour Down Under, an event he was paid $1,000,000 to compete in. According to UCI regulations Armstrong should never have been on the start list, having failed to announce his comeback and return to the athletes’ testing pool within a necessary six-month window. According to the CIRC report the consensus within the UCI was that Armstrong should be held back from competition until February of 2009, at which point he would have completed the six-month testing. However this would have meant missing the Tour Down Under, which took place in January.

According to the report McQuaid initially informed Armstrong on October 2, 2008 that the Tour Down Under was not possible. However the UCI leader had a sudden change of heart and on October 6 “advised his senior team that he had decided that Lance Armstrong could ride the Tour Down Under.”

Within the CIRC report, “several interviewees spoke about an abrupt “change of mind” by the UCI President that took many people at UCI by surprise and underlined the fact that the decision was unilaterally taken by the UCI President. No explanation was then given internally as to why Lance Armstrong was suddenly given an exemption to ride the Tour Down Under.”

On October 6 Armstrong also announced that he would also take part in the Tour of Ireland later that year, a race in which McQuaid’s brother, Darach, was the Project Director. Armstrong later announced that he would hold his Livestrong summit in Dublin, just days after the race.

“When Pat McQuaid made the decision to allow Lance Armstrong to compete in the Tour Down Under, UCI failed to apply its own rules by not applying Article 77 of the 2008 UCI ADR. In doing so, UCI damaged its reputation by sending the message that rules applied differently to some athletes compared to the rest of the peloton,” reads the report.

The report also adds that the decision over whether Armstrong was eligible to the ride the Tour Down Under was one that the UCI’s Management Committee should have made, and not just the President.

Nike watches and handshakes

The close ties between the UCI presidents and Armstrong stretched far outside of the mere sporting arena as Verbruggen and McQuaid sought not only to piggyback and enhance Armstrong’s success but milk the glory too. The rider was asked on ‘numerous occasions’ to “send letters of support or gifts or to meet people suffering from cancer whom they knew. Personal favours were also asked such as requests for Nike watches for the family members of a former UCI President.”

Verbruggen also helped draft an open letter for Armstrong in which the rider attacked the credibility of Dick Pound, and the rider was also asked to sign a letter of support of the ProTour while the UCI fought with ASO.

USADA and the final battle

The final act of collaboration between Armstrong and UCI occurred during the battle for jurisdiction in USADA’s pursuit of the US Postal team in 2012. Initially the UCI appeared reticent in their concern for the matter with McQuaid telling Cyclingnews that, ‘the UCI has already said that we’re not involved in this investigation and our last press release we said we would not comment. So don’t ask me. If you want to talk about it ask USADA, not me.”

Two days later the UCI told USADA that jurisdiction lay with them and that the case should be handed over immediately. At the same time Armstrong’s legal team were building a case for the UCI’s new stance, with CIRC confirming that the “UCI was in frequent communication with Lance Armstrong and/or his lawyers between June and September 2012.”

Thank you for reading 5 articles in the past 30 days*

Join now for unlimited access

Enjoy your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

*Read any 5 articles for free in each 30-day period, this automatically resets

After your trial you will be billed £4.99 $7.99 €5.99 per month, cancel anytime. Or sign up for one year for just £49 $79 €59

Join now for unlimited access

Try your first month for just £1 / $1 / €1

Daniel Benson was the Editor in Chief at Cyclingnews.com between 2008 and 2022. Based in the UK, he joined the Cyclingnews team in 2008 as the site's first UK-based Managing Editor. In that time, he reported on over a dozen editions of the Tour de France, several World Championships, the Tour Down Under, Spring Classics, and the London 2012 Olympic Games. With the help of the excellent editorial team, he ran the coverage on Cyclingnews and has interviewed leading figures in the sport including UCI Presidents and Tour de France winners.